|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 23 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

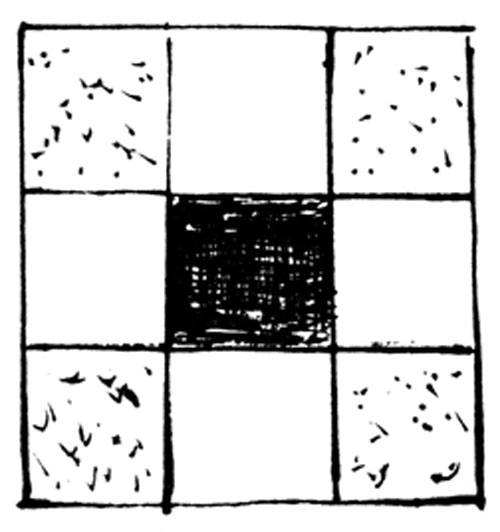

Source: July 1985 Volume 23 Number 3, Pages 99–106 Quilt Patterns in American History Quilt making in America began as a salvaging activity. The settlers probably brought quilts with them from Europe, but to insure a continuing supply of warm bedcovers for their families, even the tiniest scraps of fabric had to be preserved. The average housewife had a plan for every piece of cloth that came into her home, such cloth coming either from the labor of the settlers or at great cost and difficulty from across the ocean. As the colonists moved inland, the imported cloth was even more scarce. Earliest examples of bedcovers made by the settlers are what we now call "crazy quilts". Materials used were often the best parts of worn woolen clothing. Irregularly cut pieces of varying sizes were fitted together in a random manner. The resulting quilt was placed over a batting and a backing, and the three parts were tied together with colored yarn. Over the years, new patches covered patches that had become worn, further befuddling the original pattern. Warmth and service were the inspiration for these early crazy patch quilts. At some point, a housewife decided to cut her patches into rectangles. This not only made a more orderly looking quilt, but also must have greatly simplified her sewing. These single patches, the same size over the entire quilt, were a move toward more than salvage; quilting was becoming a salvage art. The earliest geometric forms used for quilting patterns were the rectangle, the square, and the diamond. The "Four Patch" and the "Nine Patch" are the oldest known block patterns. Both were made entirely of squares, and they early-on featured light and dark divisions.

Four Patch

Nine Patch In these early quilts, the scrap tradition was evident. Overall planning with a few basic colors was rarely possible. Often even the patches were patched! The diamond pattern was used for "Tumbling Blocks", or "Baby Blocks", quilts. Corners had to be matched with great care for this pattern, which featured an unusual geometric effect. Quilts of this pattern were designated as more luxurious than the square block patterns. Two of our presidents, when children, quilted with their mothers - Dwight Eisenhower and Calvin Coolidge. The quilts that they worked on now hang in museums dedicated to them. Both of these quilts were made with the "Tumbling Blocks" pattern.

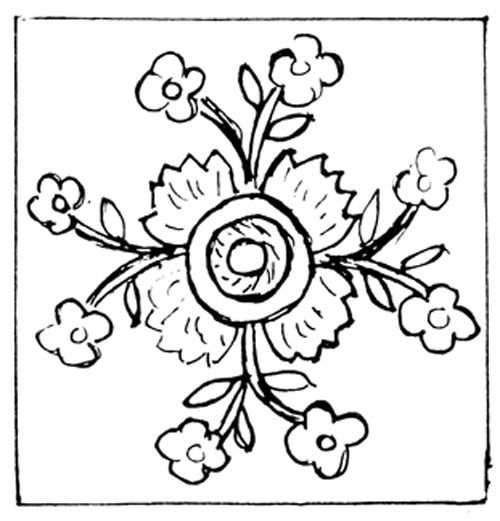

Log Cabin "Log Cabin" patterns, the "Roman Stripe", the "Roman Square"," and "Brick Work" were all patterns developed with the use of cloth cut in strips. The "Log Cabin" is pieced with rectangular strips around a center square, usually red and representing the door of the cabin. The strips surrounding the center are light on one side and dark on the other, forming two contrasting triangles. The placement of the lights and darks creates the overall quilt pattern. Such patterns have been given identifying names: "Barn Raising", "Sunshine and Shadow", and "Straight Furrow" are the most common. The "Crazy Quilt", the "Roman Stripe", and the "Log Cabin" quilts that were to appear late in the nineteenth century in a more luxurious form in silk and velvet were often designed with coordinating black strips. Such strips were plentiful then, for they were cut from the voluminous black taffeta skirts of the period, after they had become worn. These quilts were not always used in the bed room; often they were displayed as throws in the living room of the home. No country in the world has had the kind of involvement with patchwork that we have had in the United States. Until around 1850, patchwork was the most important element in quilting. Applique quilts were made from "whole cloth" and kept for the wedding bed or company, or perhaps stored away and never used at all. Patchwork quilts, on the other hand, were worn out with every-day use; and so, ironically, the early appliqued quilt is the one that more likely survived and thus came down through the generations. The rose was a popular theme of the nineteenth century. Adaptations as small as a change from a bud to a flower would change a pattern name, so rose pattern identification is complex. Almost any pattern with any resemblance to a rose was at some time called "Rose of Sharon".

Whip Rose or Democratic Rose One of the nost beautiful of the old rose patterns was the "Whig Rose", with its vines and flowers trailing out from a beautifully appliqued center. Women whose husbands were of a different political persuasion were still able to use this pattern by simply renaming it the "Democratic Rose", and so it appears to this day under both names. Medallion-type quilts are another of the luxury varieties. These quilt shave a center theme, pattern, or picture, surrounded by one, a few, or many borders. Early medallion quilts might have had an exquisite imported picture in the center. An elaborately appliqued center of flowers, with a trailing vine and flower border, was another quilt of this type. White on white quilts, with their elaborate needlework, were often made with center medallions. A medallion quilt made by Martha Washington around 1790 is a possession prized by the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association. It has a printed cloth center, portraying William Penn's Treaty with the Indians, surrounded by pinwheel patchwork blocks. The traditional patchwork star block named for Martha Washington features a pinwheel center. (Most likely the creator of this block made a connection here, but details of this are lost in history.)

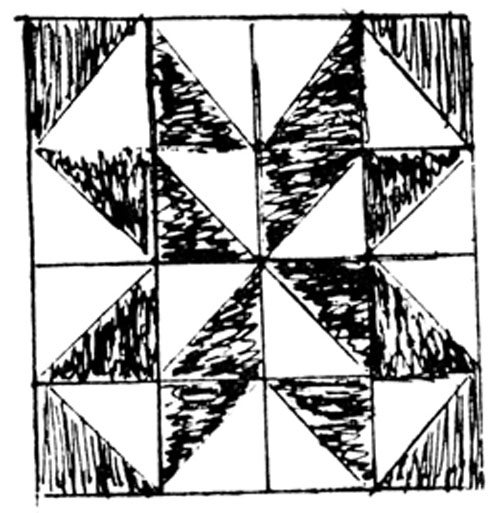

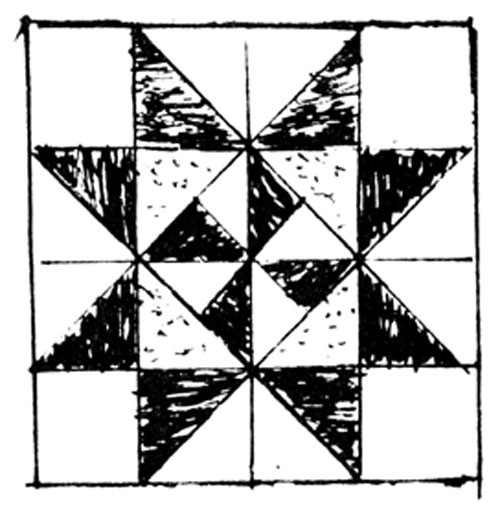

Barbara Frietchie Star

Martha Washington Star

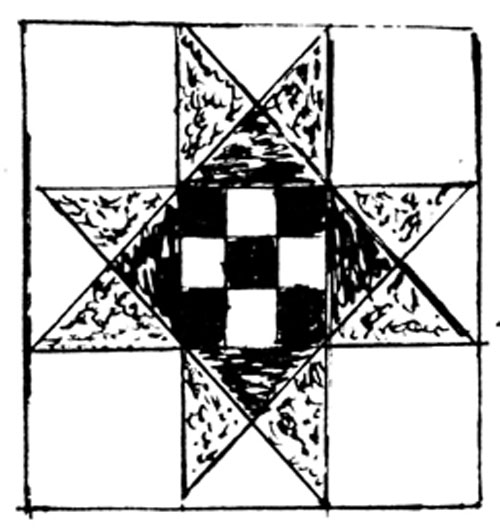

Dolley Madison Star Star patterns are the most numerous of all quilt patterns, probably because they can be created in infinite variety and carried to successful completion by any reasonably competent seamstress. They were named for heroines: "Barbara Frietchie", "Martha Washington", "Dolley Madison"; for states" the "Ohio Star", "Virginia Star", "Texas Star"; for times of day: "Morning Star", "Evening Star"; and on and on. One star certainly in the lead in popularity is the "Variable Star", also known as "Eight Point Design", "Flying Crows", "Lone Star", "Ohio Star", and "Texas Star", among other designations. This block is a straight-forward design, capable of many color variations and creative possibilities. Periods, personalities, and events in history are noted in quilt design. One very visual portrayal in purely geometric form is a block named "Burgoyne Surrounded". This block is always made in red and white. Four large red square blocks are at the center of a white field. Twenty tiny red blocks are at the corners, and between them are small red bars. Marching in from adjoining fields are lines of more of the tiny red blocks. The move from pattern inspiration to pattern construction was not an easy task for the early house-wife. Her lack of measuring tools was not to hold her back, however, as she used her dishes and folded paper to expand her supply of quilting block patterns, One can imagine a "Drunkard's Path" being made from a square and a teacup, or the "Wedding Ring" being doubled with lines traced around her dinner plates. Even though such patterns were widely copied, someone first had to design them. Generalizations can be made about the regionalism of quilt patterns, but only with caution that complete conformity is never seen. Trends were visible, however. New England patterns show a solid sureness, with an avoidance of the really time-consuming patterns. Work by the Dutch and German women reflects more experimentation. Their bright colors and unique pattern exploration show more willingness to chance and fail and try again. This difference has been attributed to the differing lifestyles. New England women were more involved in community affairs, while the Dutch and German women's devotion was almost completely to the home. In the south, quilt fashions reflect that region's love of luxury, and are characterized by exquisite needlework. The "Baltimore Brides" quilt, a beautifully appliqued album type, exemplifies this. In spite of such regionalism, using quilt block patterns to determine a quilt's origin is unreliable. Patterns moved to all quiltdom, and the names were changed to accommodate the new location, making the design relevant to the quilt maker. Thus we see a coastal design, "Lost Ship", became "Rocky Glen" when used inland; "Washington Sidewalk" became the "Chicago Pavements"; "Ohio Star" became the "Texas Star"; and "Clay's Choice" became "Star of the West". Amish patterns are the exception to this. They were not widely copied until recently, and their strong colors and bold geometric designs clearly identify their origin. Students of a particular culture have a better feeling for identity within their specialty. The Goschenhoppen Quilt Show in 1984 brought out patterns particular to this northern Perkiomen Valley culture. One is the "Vine Patch", diagonally cut into light and dark halves and arranged in an overall quilt pattern much as the "Log Cabin" is used. Another is their "Pie Quilt" block, a hexagonal block of six triangles, with points meeting in the middle, giving it the look of a pie cut. A mixture of patterned and plain blocks shapes the quilt design. Signed "album" quilts are among the most valuable for collectors. One of the most cherished of these quilts is the "Circuit Rider's Quilt" now hanging in the Chicago Art Institute. This appliqued quilt was made by the women of the United Brethren Church of Miami, Ohio in 1862. The quilt typifies what makes a quilt valuable: it was presented to the Rev. C. C. Warvell, who himself was an historical personage; the women signed their blocks, and their names are among those important in Ohio history as well as among leaders in the state today; and, finally, the blocks represent each maker's idea of beauty and symmetry, and were so well done that most could stand alone as a theme for an entire quilt. These blocks have been reproduced for use by today's quilters. Religious beliefs have woven a strong thread through quilting patterns. "Jacob's Ladder", with climbing blocks; "Golgatha", with three crosses, the "Star of Bethlehem" name in a number of interpretations, "The Crown of David" - these are some of the religious block patterns that come to mind. In some religious communities, the quilter was cautioned that "only God is perfect", and she was not to take pride in a perfect quilt. If she had not made a mistake in her work, she should make one deliberately! Sometimes these deliberate mistakes were slight - but sometimes not, too. If you see a very pale block in an otherwise brightly colored quilt, or that a particular material has faded, it is more likely really to be the quilter's "humility" patch! Embroidery has also taken a place in quilting. Embroidered birds and flowers are around in abundance, and so is the cross stitch. One unique kind of twentieth century embroidery is "Red Work", turkey red embroidery on stamped blocks, purchased for a penny at the five-and-ten cent store or its local equivalent. After these blocks were placed together, the seams were feather stitched or cross stitched. This work was done in such abundance in the early part of this century that these blocks are still readily found at antique sales.

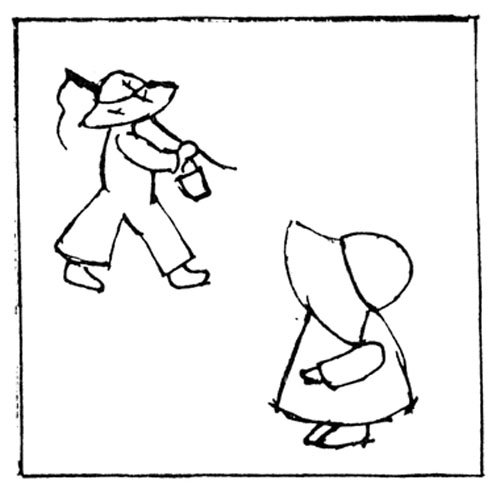

Sunbonnet Children Some of the best loved patterns of the early twentieth century were in the "Sunbonnet Babies" series. "Sunbonnet Sue", "Fishing Freddie", "Overall Bill", the "Sunflower Babies" themselves, directly from their primer all were part of this series - children whose faces were hidden by large hats. We are indebted to a woman in Kansas, Betty Hagerman, who in 1979 wrote a history of this art. She went searching for enough of these patterns to make a sampler quilt, and found more than she could use. So she not only made her prize-winning quilt, "A Meeting of the Sunbonnet Children", but also compiled the patterns and history into a book of the same name. Inspiration for these patterns came first of all from Kate Greenaway's charming drawings of English children, then developed further through Beatrice Corbett's "Sunbonnet Babies", and finally moved into needlework catalogs from then on. Quilts of the 20's and 30's were often made in light colors - peach, seafoam green, baby blue. Sometimes such colors were combined with muslin, or natural food bag material. Such quilts had a soft, muted appearance, and until recent years brightly colored quilts were seen as the most valuable to collect. But now these pale quilts, a significant representation of their time, are highly valued too. From this period, too, we find a particular type of applique that is embroidered and finished with an outline of the pattern in pink blanket stitch. Quilting activities diminished during the 40's as World War II made new demands on women. No re-awakening of the art seemed apparent for the next two decades, and in the the 60's the preponderance of double-knit polyester in the fabric stores did little to stimulate hand sewing. For a time, quilting was looked upon as a fund raising activity for country churches, and what was being done was not particularly innovative. Then came the 70's, with communities across the country reviving the traditional domestic arts as a part of their bicentennial celebrations. Groups that had never quilted before were putting together commemorative quilts with the help of a dedicated handful of women who had never left the art. The country seemed eager to get back to this kind of natural activity, and to create something enduring. Everywhere was a dissatisfaction with the growing plastic, throw-away society. From the 70's on, quilting moved to a new phase that was to be the strongest in our history to date. Fabric makers responded to this re-awakening with cotton-polyester blends in calicos of bright colors. Ten years ago, pure cotton fabrics were hard to find. Today if a quilter has some of the blended fabrics of a decade ago in reserve she uses them in a limited number of patterns, such as the "Dresden Plate" or "Grandmother's Flower Garden". For now we have pure cottons in the softer colors and the patterns of our earlier years. Much of this cloth is coming to us from China, coming in colorless, to be dyed in colonial patterns in American mills. Today's quilter not only has the wonderful selection of fabric, but she also has the tools and precise patterns that were not available to the housewife of a century or two ago. She is also instructed in better sewing methods, concerned with the straight of the fabric and avoiding selvages - luxuries that the salvage quilter never knew. Today's copy of a traditional quilt can be quite excellent. A new kind of quilter, not content to reproduce the past, is also in the field. Educated in our art and engineering schools, these women have brought new visions and new capacities to quilting. Among these gifted women are those who generously give of their talents to teach the skills of pattern construction and the mysteries of color selection, opening up a lifetime of creative expression and artistic growth for their students. Jinny Beyer, of Virginia, is one of these gifted women, and she has added a whole new dimension to quilting, both with her own medallion quilts and those of her students. She has always recognized the contribution of the women of the past centuries who, nameless though they were, were responsible for the trunks, roots and branches of quilting. The books written by Jinny Beyer that identify and classify the patterns of our heritage are merging the old forms with the new. The quilter today has so many patterns available to her that pattern study alone could be a satisfying involvement - even if she never reached for a needle. More likely, though, she will have two or three quilts or quilting projects underway! Whatever she decides to interpret with her cloth and pattern will be her contribution to the art and history of our years. TopSources Beyer, Jinny, Medallion Quilts. EPM Publications, 1982 - The Quilter's Album of Blocks and Borders. EPM Publications, 1980 Bishop, Robert; Secord, William; and Weissman, Judith R., Quilts. Coverlets. Rugs and Samplers. Alfred Knopf Co., 1982 Hall, Carrie and Kretsinger, Rose G., The Roamnce of the Patchowrk Quilt in America. 1935. Caxton Printers, reprinted, Bonanza Books Hagerman, Betty J., A Meeting of the Sunbonnet Children. Baldwin City, 1979 Hechtsinger, Adelaide, American Quilts. Quilting and Patchwork. Garland books, 1974 Lichten, Frances, Folk Art _of Rural America. Charles Scribner & Sons, 1940 Obenchain, Mabel, White House Quilts. Pattern Services News, c. 1976 Roan, Nancy and Gehret, Ellen J., Just a Quilt. Goschenhoppen Historians, 1984 Drawings by the author |