|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 30 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: July 1992 Volume 30 Number 3, Pages 87–100 The Amusement Park on the Trolley Line In the first quarter of this century the term "trolley park" was contrived to identify an amusement park or picnic park owned and operated by a trolley line. Actually, there were no trolley lines or trolley parks in either Tredyffrin or Easttown townships -- the all-powerful Pennsylvania Railroad discouraged such development in its operating territory -- but when the P&W relocated its terminus for its line from Upper Darby to Strafford in 1911 some interesting developments ensued, which led to a trolley park just over the North Valley Hill, in Schuylkill Township, not more than two miles from Tredyffrin. This is the story of Valley Park, as it was called, and its brief season as a place of amusement from 1912 to 1923. It is also the story of five other trolley parks, located within twenty miles of Tredyffrin and Easttown, which had opened earlier, during the first wave of trolley development, in the final decade of the nineteenth century. (As a matter of interest, it was just 100 years ago this spring that the West Chester trolley began to transport pleasure seekers to Lenape Park.) The technology which permitted the construction and operation of high speed rail electric cars had emanated from the laboratories of Thomas Edison at Menlo Park, New Jersey, particularly the improvements in electric distribution systems and dynamos so that power could be produced for commercial purposes. Charles Van Depoele, the "father of the trolley", first successfully applied the new technology in an electric railway in South Bend, Indiana in 1885. Trolley Parks located within 20 miles of Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships

* Park continued as Lenape Park until 1975, when it became a picnic area known first as Main Line Park and now is called Brandywine Park ** Park closed in 1905, but trolley ran until 1954 Two years later Frank Sprague, who had been an assistant to Edison for a brief period, installed the first practical city-wide trolley railway in the United States, in Richmond, Virginia in 1887. In the next twenty-five years the electric street railway spread in amazing fashion. West Chester had its first electric cars operating in 1891, Pottstown, in 1893, Norristown, the same year, and Phoenixville, in 1899. Trolleys made it possible for the workingman to live beyond walking distance of his job. The greater financial independence of the growing middle class led it to seek pleasure beyond its immediate neighborhoods. One thing the trolley operators had in common was the need for a traffic builder to enhance revenue, and for many of them an amusement part strategically located outside of town succeeded admirably. The parks were designed as a place to go for picnics, band concerts, swimming, boating, baseball, and perhaps a carousel or other amusement ride or two. Rides to and from the parks on the open-air trolleys were almost as exciting as the rides at their destinations. The West Chester Street Railway Company lost little time in establishing Lenape Park as a destination accessible by trolley, about four miles south of West Chester, on the Brandywine. In-town service on the West Chester line was inaugurated in 1891, and by early the next year work had begun on erecting a picnic and amusement park at Lenape. By 1894 a pavilion and boardwalk had been built along the river, for dancing and concerts. Later a dam was thrown across the river to provide for swimming and canoeing in the summer and for skating in the winter. In 1906 a shooting gallery and small merry-go-round were added. That same year the list of picnickers there included the Paoli Episcopal Sunday School. In those days the round-trip fare on the Pennsylvania Railroad to West Chester from Paoli, via Malvern, was $.40 for adults and $.25 for children. Once in West Chester, the trolley fare to Lenape and return was another $.15. The West Chester Daily Local News in May 1923 reported that the Paoli Sunday School was returning for its 18th annual picnic on June 16. In the 1920s the park introduced new rides and attractions, including a 1,400-foot roller coaster and a new swimming pool, fed from three deep artesian wells. But by far the favorite entertainment on the grounds was the Gustav and William Dentzel carousel, put together in 1926 from parts which had seen service elsewhere earlier. It was not the most expensive model available, but the 48 hand-carved figures were meticulously cared for by John V. Gibney, who managed the park for over fifty years. Lenape Park became the place for picnic outings each summer by Sunday Schools, fraternal organizations, "old fiddlers", and many other groups. It was, in fact, to survive the demise of the trolley line in 1929 and continue as a first-rate summer attraction until 1976, when Gibney, then 92 years old, sold it.

from the author's collection Bird's-eye view of Sanatoga Park Located over the Schuylkill river, in Lower Pottsgrove Township in Montgomery County, Sanatoga Park was the eastern terminus of the trolley line operated by the Pottstown Passenger Railway Company. The line covered a distance of about five miles, from Stowe, on the west, through Pottstown, and on to the east to Sanatoga. It was completed to the park in 1893. Early advertisements for the park called attention to its 40 acres of woodland and its lake. Sanatoga lake, 300 feet wide and over half a mile long, delighted visitors. Surrounding it were shaded paths, wooden bridges and rustic pavilions. Boats and canoes could be rented, and a naphtha launch carried as many as 18 persons at a time up and down the waters. There was also a swimming pool, complete with diving board, in a fenced off portion of the lake. But Sanatoga was mainly an amusement center. The premier amusement ride was the "Alpine Dip", a roller coaster which dominated the hillside to the east of the lake. It was nearly a mile long and was constructed especially for Sanatoga Park by the Philadelphia Roller Toboggan Company at a cost of $100,000. It is said to have been the first ride of its kind built in an amusement park, although a more sedate scenic railway appears to have preceded it in operation at Sanatoga. Other amusements included the "Palace" carousel, the "Curtiss" aeroplane, and the "Whip". Music also drew people to the park -- "name" dance bands at the pavilion on Saturday nights and a quartet for dancing week-nights and Saturday afternoons. Well known bands, including Creatore and his band, gave concerts in the park on Sunday afternoons. There were excellent facilities for baseball in the park and games were scheduled each Sunday afternoon during spring and summer. The most famous of those who participated was Bobby Shantz. A native of Sanatoga, he went on to fame as a star pitcher for the Philadelphia Athletics. A second trolley line began to serve Sanatoga Park in 1915. Track was laid between Sanatoga and Linfield, to the east, by the Pottstown and Phoenixville Railway Company. At 11 p.m. closing time for the park six to eight trolleys on the two lines would be waiting to transport the last patrons home. The Linfield extension, a shaky enterprise at best, folded in 1927. Sanatoga Park attracted most of the Pottstown area Sunday Schools for their annual picnics. In addition, many large groups from Philadelphia held annual picnics there, traveling by train to the Sanatoga station on the Reading Line and then walking about a half mile to the Dark. The park continued to operate until the last trolley service in Pottstown was discontinued in 1937. Pottstown could claim a second trolley line, the Ringing Rocks Electric Railway Company, and a second trolley park in 1894. The line purchased a 112-acre farm north of town, and turned it into Ringing Rocks Park, which was described as "a place of nature and wild beauty". A unique attraction was a large glacial moraine, covering nearly two acres of ground, the rocks piled one on another. When struck with a hammer or other hard object they could be heard a mile away, resounding over the hillside in bell-like tones ranging across the musical scale. Geologists believe that such rock deposits exist in only six places in the world. In the "east park" was the beautiful, though small, Lake Minnetoba, fed by spring water, and there were also interesting rock formations, given such names as "Hay Stack", "Bullfrog", "Table", and "the Caves". The high elevation of the property, on what local residents called "Ringing Hill", was enhanced by the erection of an 80-foot high iron observation tower, from which, using field glasses, one could see Boyertown, Phoenixville, Paoli, and the mountains immediately before Reading. The park was a "family" park, with more picnicking than amusements. . But while families went there primarily for the ride and a picnic in the beautiful woods and notwithstanding the natural beauty of the area, other attractions did appear. Work was begun in 1895 on a "Scenic Switchback Railway", a roller coaster designed by the Neshaminy Falls Amusement Association. When completed, it was more than 4,000 feet in length. A two-story pavilion, 70 by 100 feet, could accommodate 200 dancing couples on one floor alone, and contained a small stage for entertainments. There was also a merry-go-round, bowling, and shuffleboard, and a menagerie featuring deer, bear, and other wild life. In 1907 the trolley line became part of the Schuylkill Valley Traction Company network and an extension to Boyertown was completed the following year. After World War I, however, declining financial results led to the abandonment of the Boyertown extension in 1927, and eventually all trolleys to the park stopped running in 1932. Meanwhile, the Philadelphia and West Chester Traction Company was completing its trolley line from 63d Street in Philadelphia to West Chester. The first trolley ran as far as Newtown Square in 1896. Plans had already been made for a trolley park, in the rough terrain of Castle Rock just west of Newtown Square. John Shimer, who was in control of the company at the time, liked the idea of having an amusement park in the area where he grew up, and, wasting no time, he prompted the traction company to buy 37 acres there in 1895. (As it turned out, this was several years before the line actually extended that far west. In the interim, a temporary park was set up' in Broomall, "Broomall Grove", which operated for a season or two.) Castle Rock was a picturesque, wooded hillside area, studded with rock masses and honeycombed with caverns, an ideal setting calculated to enchant the children among the its visitors. It had gained notoriety in history as a region frequented by the famed highwayman James Fitzpatrick, a Revolutionary War deserter from the American cause who terrorized the Chester County countryside during the latter part of 1777 and early 1778. He took particular delight in robbing Whig tax collectors and local taverns, but was finally captured on August 22, 1778 at the house of William McAfee, near Crum Creek and Castle Rock. He was hanged in Chester jail on September 26. Readers of Bayard Taylor's The_ Story of_ Kennett will recognize this character as Sandy Flash. Although the name of the area was Castle Rock, for some reason the company named what Ronald DeGraw called, "its glorified picnic grove" Castle Rocks Park. The park, which lay about two miles beyond Newtown Square on the south side of the West Chester Road where it crosses Crum Creek, was officially opened on Memorial Day in 1899, shortly after the trolleys began running to West Chester. The new park presented to its visitors a steam-powered merry-go-round, a shooting gallery, a small restaurant, a dance pavilion, picnic grounds along Crum Creek, fishing in the stream, hammocks and swings, and balloon ascensions and fireworks on the Fourth of July. An orchestra played on Saturday afternoons and every night except Sunday during June, July and August. Featured was a "noted cornetist", William Northcutt, who performed from a perch on a high rock on weekends. The traction company catered to Sunday School and company picnics. At least one Sabbath School from a church in Berwyn held its annual picnic there at the turn of the century. Although only five miles away as the crow flies, the location was somewhat inconvenient for this area, with no public transportation available in the area north of the park. Horses and wagons had to be rented from local livery stables to transport the picnickers to the park. Unfortunately, Castle Rocks was also a long distance from its principal constituencies: residents of West Chester had to travel only half as far to reach Lenape Park, and Philadelphians found Willow Grove or Woodside parks much closer, and much bigger. Thus Castle Rocks suffered from a persistent lack of patronage, and it was closed after only seven seasons, in 1905. Sunday Schools continued to hold picnics at its location, but finally in 1926 the traction company divested itself of most of its park real estate. The Montgomery and Chester Electric Railway, or M&C, opened in 1899, providing local trolley service in Phoenixville and also connecting that borough with Spring City to the west. (The original line was broken at Ironsides, just west of Phoenixville, where the Pickering Valley Railroad prevented the operation of through cars between the two boroughs. Thus the M&C ran cars from both ends of the line, meeting at Ironsides, where the passengers were compelled to change cars, one car taking them as far as the railroad crossing and the other picking them up at that point. The trip between Phoenixville and Spring City required 40 minutes. Finally, in 1908 arrangement was made with the Pickering Valley Railroad to permit building a trestle 517 feet long, bridging the railroad right of way so that it was no longer necessary for passengers to pile out and change cars.) Bonnie Brae Park was built along the line in 1901. It offered picnic grounds, light refreshments and various amusements; later it had movies, too, when they became popular. The park was located about midway between Phoenixville and Spring City in East Pikeland Township, along the south side of the old Schuylkill Road. A carriage road separated it and Zion Lutheran Church, where Henry Muhlenberg was the first preacher. The name "bonnie brae" was aptly bestowed upon the park. True to name, there is a brae (Scots for hillside, slope, bank, as of a river valley) which is bonnie (handsome, beautiful). The eminence overlooks the Schuylkill Valley, including portions of Berks and Montgomery counties. Spring City is in full view and the Bonnie Brae Farm of David MacFeat stands on the same side of the Schuylkill Road just west of the park and church. It is likely that this Scotsman or his ancestors are responsible for the apt name designation. In 1907 a Daily Local News reporter wrote, "it seems to fill the bill as a park in that it has many attractions in the way of a zoo, afternoon and evening concerts, a respectable carousel, steam driven, and an auditorium. It is a Mecca of the Sunday School and other picnics, without dance platform or questionable games. From dromedary to monkeys the animals are in good condition and the elk has immense horns. Ponies and goats carry children a number of times around a fenced circle at the price of a dime a head." Trolley service on the M&C terminated July 8, 1924, but there is a newspaper report as late as 1938 of use of the park for public gatherings. Highway construction ultimately forever changed the face of the "bonnie brae": the Daily Local News reported on August 14, 1940, "a landmark which has stood for more than a generation was being razed today to make a way for the relocation of the Schuylkill Road. Workmen began the task of removing the frame building which once served as the trolley station at Bonnie Brae park. ... Since the passing of the trolley the park was purchased by other interests and the trolley station enclosed to serve as a storage building. The proposed new concrete road has caused the telephone and electric lines to be moved and demolition of the station is part of the clearance work." In general, the trolley lines established in the 1890s prospered during the first decade of the twentieth century. But there was in motion a force which the trolley operators would soon have to reckon with. Just as the speed and convenience of the trolley had permitted its rapid growth against the competition of the steam railroads, so the even greater convenience of the automobile was about to overtake the trolley. Over half a million cars and trucks had been built between 1900 and 1910, and the number built would swell to nearly 2.6 million in the next five years. In the year 1907, however, it was still business as usual for the trolley magnates. The opening of the Market Street Elevated Railway in Philadelphia to 69th Street and the completion of the Philadelphia and Western, or P&W, to Strafford seemed to inspire a rush by trolley promoters to project the next link westward in this rapid transit network. In the fall of 1907, however, there was an interruption in the business prosperity, precipitated by bank closings in New York City, and the so-called Panic of 1907 was followed by a business depression. Notwithstanding the general economic malaise, Thomas E. 0'Connell, a promoter and the builder of a number of Chester County electric railways, appeared in Phoenixville in November 1909 to organize an effort to construct a trolley line from Phoenixville to Valley Forge and then on past the residence of Secretary of State Philander C. Knox to Strafford, where direct connection would be made with Philadelphia by way of the P&W. Early on there was also mention of the possibility of running a spur from Valley Forge to Bridgeport, opposite Norristown. 0'Connell was a veteran electric railway builder, having had a hand in constructing, among others, the lines between Llanerch and West Chester, Lenape and Kennett Square, West Chester and Downingtown, and a line at Bowie, Maryland. The Phoenixville to Valley Forge project would bring his total construction of trolley lines in Chester County to more than 75 miles. As a promoter, he was a cheer leader of sorts -- enthusiastic, assertive, entertaining in speech. He could argue, and did argue, masterfully; his was pure Irish wit. He was not fearful about various contracts, always giving fair and best to his work. Interviewed in West Chester upon his return from two days of meetings in Phoenixville promoting his new venture, he said this was his best trolley project yet, and that he was very sanguine about its success. At two public meetings in Phoenixville he told of the advantages of the new line, noting that it would take about $60,000 to capitalize the new road and that before a new charter could be obtained $20,000 would have to be subscribed. The citizens responded very liberally to the proposal, with $12,000 subscribed at the first meeting and ten per cent of that actually paid into the treasurer. O'Connell afterward reported, "It was the most enthusiastic meeting I ever had, and the best men are with me. Look at the names, and Phoenixville has pride and enterprise that can back it up." But while the Phoenixville business community was caught up in the infectious optimism of the moment, O'Connell may have oversold the project, promising more than he could deliver. Apparently he had not discussed his project with the Valley Forge Park Commission, which would have to grant a right of way for construction. Nevertheless, maps were provided by the company for inclusion in the Guide to Valley Forge, published by the Rev. W. Herbert Burk in 1910, showing in detail the route of the trolley line under construction. At the same time, in a Valley Forge Guide and Hand-Book by the Rev. James W. Riddle, also published in 1910, the trolley line was described as extending through the park. Writing in the Phoenixville Daily Republican in April of 1952, Phoebe H. Gilkyson, the widow of one of the investors in the trolley line, noted, "The late Thomas 0'Connell conceived the idea of linking Phoenixville with Valley Forge and eventually the 'Main Line' via Strafford, and although he had more ideas than funds [many canny citizens] put money into the project." Eventually the new line did get built to the east -- but only as far as Valley Forge. In 1913 the completion of a bridge bringing the trolley across Valley Creek, to the corner where Valley Creek Road turns toward Tredyffrin, closed out the construction. For whatever reason, lack of right of way or lack of funds, that was as close to Strafford as the line ever got. The official name of the line, as specified in its charter, was the Phoenixville, Valley Forge and Strafford Electric Railway Company, but it came to be known simply as the Valley Forge line. The line left Phoenixville on Nutt Road, travelling east to Corner Stores, and from there proceeded south along the east side of White Horse Road, bridged the Pickering Creek, turned left at Williams Corner onto Clothier Spring Road and then left again at the Pickering School onto the back road to Valley Forge today called Valley Park Road. It was here, about mid-way between Phoenixville and Valley Forge, that O'Connell built the trolley line's amusement park, named Valley Park. It was located on the south side of the road, about a half-mile west of the intersection of the road with Country Club Road, adjacent to the Anderson family graveyard.

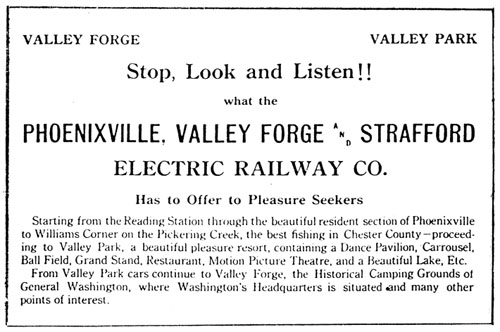

courtesy Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area Early advertisement for Valley Park (It is an historic site in its own right. A hundred and fifty years ago or more it was a private burial ground, and in it repose the remains of the mother of one-time Republican boss Matthew Stanley Quay; she was a daughter of Patrick Anderson and related to the Anderson clan which traces its roots back to the union of James Anderson and Elizabeth Jerman, of Jerman's Mill in Tredyffrin Township.) Valley Park opened on Sunday, August 4, 1912. The first day was marked by a well-attended performance of the Phoenix Military Band, beginning at two o'clock in the afternoon. In the park a concourse led south from the trolley stop and Valley Park Road, with picnic areas and amusements aligned along the side. Things were actually pretty primitive that first summer. Some of the ground was low-lying wetlands, and not very attractive, but over the off-season improvements were planned. The following March the company announced that it had purchased eight acres of ground from Gen. B. F. Fisher, adjoining the park, and that it would build a lake covering part of the original park and about two-thirds of the Fisher tract. (Fisher had lived across the road from what was to become the park since 1874. He was an authentic hero of the Civil War, having risen from the rank of lieutenant to brigadier general. During his army career he had been captured by Confederate troops, confined at Libby Prison in Richmond for seven months, and escaped with other men through a tunnel they dug. He died at his home near the park on September 8, 1915.) An up-to-date merry-go-round and various other attractions were also promised as special features for the new park in the coming season. Improvements did in fact materialize, and the park succeeded in building a faithful following of devotees which did much to encourage ridership on the Valley Forge line. John V. Norris, Phoenixville historian and newspaper columnist, writing in the Evening Phoenix in 1977, related that many "still recall the free movie theater that O'Connell operated as a magnet to get the people to the park. These movies were the silent ones that were inexpensive to rent from Philadelphia. At that time there were no such things as talkies. Another attraction was the dance hall, usually packed on Saturday nights at 35 cents a head. A three-piece orchestra could be had for three hours, 8 to 11 p.m., for $45. They weren't the best and they weren't the worst. They would never make the Lawrence Welk unit. "There were a number of other concessions," Norris continued, "like knocking over ducks with a pop gun, operating 'bump cars' and guessing weights to name just a few. There was also a small lake or pond in front of the merry-go-round for those who wished to go boating." It was no more than a couple of acres in size. Ellis Roberts, who grew up in the neighborhood next to the park, remembers that there was an ice house nearby and that they cut ice off the pond and filled it in the winter. "It cost nothing to watch a baseball game on the park's diamond," Norris also noted. "Some of the visiting teams were more fun to watch than some major league games. The seats were not the most comfortable [boards or planks across stumps] but what does one expect 'for free'? In 1916 the famous Bloomer Girls, who hailed from Philadelphia, attracted the biggest crowd in the history of the park. It took the big summer trolley several round trips to transport the crowds back to Phoenixville. O'Connell also pressed into service two of the winter cars (only half as big) for several trips to get the people back [home]. The younger ones hiked to Phoenixville, thereby saving 10 cents." The merry-go-round at Valley Park, according to Norris, "was one of the most beautiful to be found anywhere. The animals were all hand carved by a German wood carver. It was exact in every detail. O'Connell told us that he had paid $9,500 for the entire unit. A few years later, he was offered twice this amount, but refused the offer. It had a beautiful sound to it. When the park was closed, the merry-go-round was sold to the owner of an amusement park in Palisades Park, New Jersey, across the Hudson river from New York City." Valley Park also provided facilities for community and school events. On June 6, 1917 the park pavillion was the scene of commencement exercises for the four one-room schools of Schuylkill Township. (Students attended the local township schools for the first eight grades, and then went on to Phoenixville High School.) Early in the day the pupils of the schools enjoyed their annual picnic at the park. Luncheon was provided, and the scholars remained for the commencement exercises in the evening, which convened at 7:30 p.m. Sabina Brittain Setzler grew up in Valley Forge. She remembers her father taking the trolley on the Valley Forge line. When the Valley Forge School burned down in 1920, two years before her graduation from eighth grade, she went to school for one year in the dance hall at Valley Park, and then for one year in the church at Valley Forge. Roberts remembers the Valley Forge line as pretty much an O'Connell family affair. Jerry O'Connell, the son of the president, ran the hot dog stand in the park. It had a kerosene stove, and when the supply of fuel ran low he would ask Roberts to hop the next trolley from Valley Forge up to the store at Williams Corner, about a mile away, to get a new supply. The next trolley on its way back from Phoenixville would provide the return trip. (The trolley company car barn and office were also located at Williams Corner, in back of where the Schuylkill Township office now stands. The story goes that after the company closed down and sold off its properties the office was moved across White Horse Road and converted into a dwelling unit still occupied today.) The park continued to be a favorite destination for many, but as the year 1919 wound down the effects of the proliferation of the automobile were unmistakable. Still, at the end of August that year, when O'Connell visited West Chester he was quoted by a representative of the Daily Local News about business conditions, "He [O'Connell] asserts that the automobile has largely hurt the suburban and interurban electric railway companies' business,", it was reported, "but believes that there are still many persons who cannot own motor cars, and hence will use trolley lines. But Mr. O'Connell differs with some trolley officials and says, 'The raising of a ride [of] reasonable distance by increasing the fare from 5 cents also raises the ire of the public and when a company or businessman get the ill will of the patrons and public, they lose patronage. A man who is angry would rather pay ten cents to an auto truck driver to carry him the same distance that he formerly paid a trolley company 5 cents for. For this reason I have not increased the fare on the 5-cent limit on our road. We still carry them three miles for the nickel.1" Commenting specifically on Valley Park, he added, "'But if a company has no large villages or much population along its route it must furnish something to draw passenger traffic. That is why we established a big park, with attractions, amusements, base ball, boating, and so forth. It cost money, but we fill our cars, at 5 cents the ride of over three miles each way. On picnic days and evenings this pays.'" But even the weather conspired to thwart the efforts of O'Connell to keep the line afloat. On January 28-29, 1922 a severe snowstorm and blizzard blanketed the county with 18-1/2 inches of snow, and many trolleys were marooned. Ellis Roberts remembers crews shovelling out the cut along Clothier Spring Road on the Valley Forge line. It had to be done in two stages; one man lifted the snow up to a bench, and then another shoveler would pitch it out of the cut. All you could see of the trolley was the pole on top. The competition of the motor car and increasing costs of operation after World War I finally led to the demise of the Valley Forge line on December 24, 1923. This also meant the end of the park, since it depended on trolleys to take the people to and from the park. "The trolley bondholders," Norris remembers, "had a special meeting to wind up the financial affairs on January 10, 1924, at the old Rialto Theater, with Thomas B. McAvoy, the well-known brick manufacturer of Perkiomen Junction, as the chairman. The special committee, which had been named several months previously to make arrangements for the sale of the trolley line, was headed by J. B. Acker and included such prominent local businessmen as Hamilton H. Gilkyson, Jr., A. W. Kley, Charles F. Bader and Leonard Grover in the group." There being no prospective purchasers, the bondholders decided to buy the line themselves and sell it for junk. This process took the remainder of the year, and the cars and other property were sold in the spring of 1925. "The bondholders of the trolley line took an awful financial beating," Norris continued. "A $5,000 bond was not worth the paper it was printed on. Rolling stock went for a ridiculous figure, the big summer cars [for] $500 and the winter cars [for] $300. Among the bondholders of note was Col. Archie M. Holding of West Chester, who owned $55,000 worth of them. He received about $6,000 back from his investment. The total amount of bonds outstanding was $320,000. The bondholders lost about 90 per cent of their money. The coupons on the bonds had paid a six per cent interest rate." The final chapter in the story of Valley Park may not yet have been written. A proposed 240-acre residential development, called Fernleigh, which is to include 325 single and multi-family houses has been before the Board of Supervisors of Schuylkill Township for a lengthy period. The approval process has given rise to a number of court cases, including one which went before the U. S. Supreme Court. The proposed development, which is further complicated by wetlands, includes the former site of Valley Park. The names of two other trolley parks or parks on the trolley lines should be added as a footnote to record their brief existence. Peoples Traction Company, P.T.C., the predecessor of Philadelphia Rapid Transit, in 1897-1898 constructed the Chestnut Hill Amusement Park, better known as "White City", just over the county line in Erdenheim in Springfield Township, off Bethlehem Pike. Apparently pressure by local residents who were displeased with its operation closed the park permanently in 1911. And when the Philadelphia and Western Railway Company opened its line in 1907 it also opened an amusement park, Beechwood Amusement Park, in Haverford Township, about five minutes from 69th Street. Financial reverses and poor management, however, led to its closing after only three summers of operation. The trolley park or amusement park on the trolley line, during the last decade of the 19th century and the early decades of the 20th century, made affordable entertainment available at a time when there was limited leisure. When such activities were also greatly restricted by limited transportation options, it provided a place to go for picnics, band concerts and dancing, swimming or boating, baseball, and perhaps a ride on the carousel or other amusements. For this reason this unique institution is fondly remembered by all who look back to the time when they took the trolley to the park. TopReferences Bowman, Stanley F. Jr. and Cox, Harold E., Trolleys of Chester County Pennsylvania. Forty Fort: Harold E. Cox, 1975 Burk, Rev. W. Herbert, Guide to Valley Forge, 2d ed. Norristown: Times Publishing Co., 1910 DeGraw, Ronald, The Red Arrow: A History of the Most Successful Suburban Transit Companies in the World. Haverford: Haverford Press, Inc. 1972 Foesig, Harry and Cox, Harold E., Trolleys of Montgomery County. Forty Fort: Harold E. Cox, 1969 Gilkyson, Phoebe H., "Our Yesterdays", Phoenixville Daily Republican, April 18, 1952 Lichtenwalner, Muriel E., Lower Pottsgrove: Crossroads of History. Lower Pottsgrove Township, Pa.: Lower Pottsgrove Bicentennial Commission, 1979 Newspaper clippings about East Pikeland township, Schuylkill township, Transportation, Valley Forge, Fisher family, and O'Connell family, in Chester County Historical Society clipping files , West Chester Norris, John V., "Purely Personal", The Evening Phoenix, October 6, 1977 Riddle, Rev. James W., Valley Forge Guide and Hand-Book. Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1910 Roberts, Ellis. Interview, May 13, 1989 Setzler, Sabina Brittain. Interview, May 13, 1989 Toll, Joan Barth and Schwager, Michael J. [eds.], Montgomery County: The Second Hundred Years. Norristown: Montgomery County Federation of Historical Societies, 1983 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||