|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||

|

Source: Fall 2004 Volume 41 Number 4, Pages 111–117 Elda Farm History and Recollections Hint for using the footnote reference links: Using the “Back” feature of your browser will return to the previous [Note] link location after you read the footnote. The Delete (Mac OS) or Back Space (Windows) keys often perform this function.

On October 2, 2004 Tredyffrin Township dedicated the new 90-acre Wilson Farm Park, located between the back of the Chesterbrook Shopping Center and Route 202. This area was formerly Elda Farm.

Elda Farm had been in the Wilson family for four generations by the time we moved there in the spring of 1930. The farm was acquired in 1836 by my great-great-grandfather David Wilson, Jr. and his wife Eliza Siter Wilson. He built the original farm buildings between 1836 and 1840. The name, Elda was an amalgam of their first names: Eliza and David. The farm was originally 101 acres, though much more recently it was reduced to 90 acres when the state widened Route 202. The land had been part of the much larger Havard Farm, known as the Lafayette Headquarters Farm for the role it played in the Revolutionary War.

David Wilson, Jr. was born in 1791 on the Wilson Homestead Farm on Swedesford Road in nearby Paoli. [Note 1] David, Jr. was the third generation of Wilsons to have lived at the Wilson Homestead. [Note 2] His father, David Wilson, Sr., was a Captain in the American Revolution. As a young man David Jr. left the Homestead Farm and moved to the village of Sitersville, now known as Strafford. It was there that he met his future wife Eliza Siter. Eliza's brother, Edward, was the keeper of an inn there called the Spread Eagle, where Old Eagle School Road meets Lancaster Avenue. The Spread Eagle Inn had a post office in it, and David served both as postmaster and host at the inn.

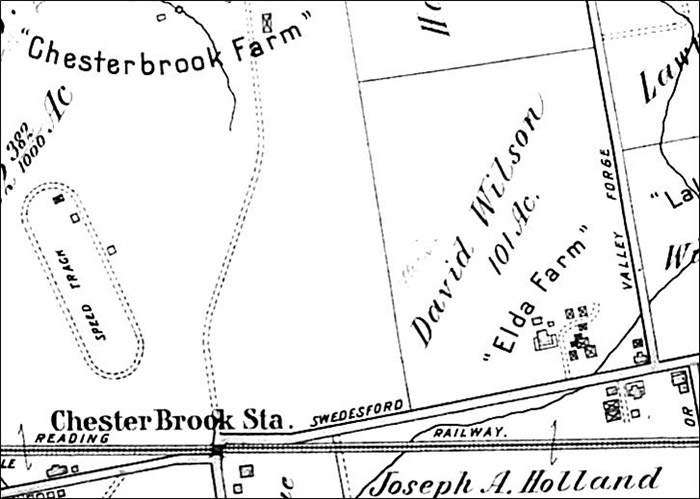

Elda Farm in 1912. The lower right corner of the farm on this map is the upper right corner of the map of Wilson Farm Park on the back cover. Eliza and David were married in 1812. For a decade or so after their marriage they lived in a house in Sitersville belonging to Eliza's family. All seven of their children were born there. As a young man, David was a "drover" of cattle - driving cattle from the more western counties to the Philadelphia market. He had became a prosperous cattle merchant by 1828 when his father David Wilson, Sr. died, leaving him the Wilson Homestead Farm. After living at the Wilson Homestead for ten years, David started building Elda Farm as a home for himself and Eliza, probably thinking that his oldest son, Edward Siter Wilson, would take possession of the Wilson Homestead. Instead, Edward married Sarah Ritter, the heiress to the Lafayette Headquarters Farm, just north of Elda Farm, and the Wilson Homestead went to David's second son, John Morton Wilson. Eliza and David lived for many years at Elda Farm, where he continued his trade in dairy cows and farmed Elda's fertile soil. He also served as a director of the Chester Valley Railroad and a bank in Norristown. David died there in 1873.

Eliza and David Wilson passed Elda Farm to their youngest son, Winfield Scott Wilson, my great-grandfather. Winfield was born in 1825 when his parents were still living in Sitersville, and he became the most successful of Eliza and David's children. He was a railroad executive who laid out the line for the Chester Valley Railroad, which ran through the Great Valley from Downingtown to Bridgeport, where it joined the Reading tracks and continued on to Philadelphia. The Chester Valley line was a one-branch line that ran parallel to Swedesford Road and served all the farms along that road. Later in life, Winfield became purchasing agent for the Reading Railroad Company, and then president of the Philadelphia, Germantown & Norristown Railroad, Pennsylvania's oldest railroad. While my great-grandfather Winfield Wilson was laying out the Chester Valley Railroad he was visited by two young railroad employees from New Hampshire, Tristam Coffin Colket and John L. Stearns. Winfield walked with them down the path of this new line from Downingtown to Bridgeport. It was a long walk, and they started early in the morning. By the time they reached Rehobeth Springs in Tredyffrin Township, they were good and hungry. Winfield suggested they stop at the farm of William and Sarah Pennypacker Walker. The Walkers predated even the Wilsons as an important early presence in the Valley. It was about time for the noon meal, and the Walkers were known to prepare great quantities of food. Besides, they had a brood of beautiful daughters, Winfield told his companions. So they went to the house and were invited to stay for dinner. Eventually all three young men - each of whom later became president of a railroad - ended up marrying Walker sisters. My great-grandfather Winfield married Emma Jane Walker in 1855. Though descended from an old Quaker family, she was an Episcopalian with a wide circle of fashionable relatives and friends. Judging from her diaries, now scattered among her descendants, Elda Farm was a lively household during the time she and Winfield operated it, literally bursting with visitors and social activity. It was a rare Sunday that did not see 15 or 20 people seated around the dinner table. During this time Elda Farm was operated by hired hands and produced a typical range of vegetable crops and livestock.

David Wilson 1860 - 1925 Winfield and Emma had four children. My grandfather, David Wilson, was born in 1860 and was the oldest son. He married Ruth Anna West, my grandmother, who came from a solid line of hardworking country Quakers. (The Wilsons remained Quakers through my own generation.) David and Ruth Anna moved to Elda Farm in 1907 after the death of Winfield's mother in 1907. At this time, David was secretary-treasurer of the Philadelphia and Reading Coal and Iron Company. At Elda Farm, Ruth Anna was not lively or outgoing as her mother-in-law had been. She preferred to remain at home and socialize with her own immediate family. But she ruled over her small domain with an iron hand. She had a large flock of sheep, and a wonderful orchard, perhaps ten acres, with every kind of fruit tree imaginable. I was told it was she who ordered the trees and supervised the planting and harvests at Elda Farm.

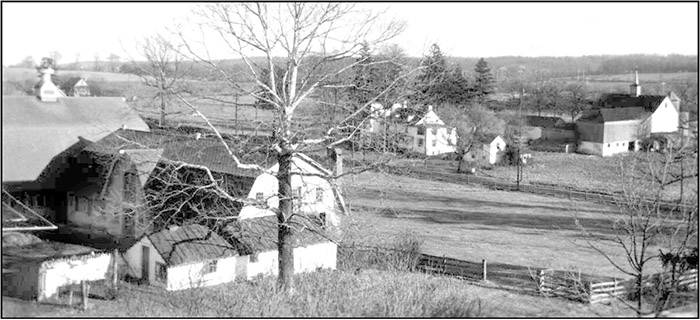

My grandfather, like his father and grandfather, never made a living from farming. Elda Farm was more of a hobby, but he invested considerable sums of money in the farm between 1907 and 1912, making it a model of progressive agriculture. David built a huge milking barn and box-stall barn, each with concrete floors, underfloor drainage, running water, asbestos-shingle roofs, and an overhead manure wagon on a rail that carried manure to an outside pile.

Above: Elda Farm barns. Below: Dairy barn.

Elda was also the first farm in the valley to have electricity. Its power system operated on direct current - unlike today's alternating current -and there was a great bank of batteries in the barn. (I believe the last of those blown-glass battery jars, which we long used for flower arrangements, was accidentally broken by my son a few years ago.) Farmers came from all over the country to see these modern barns. David had a prize-winning herd of Guernsey cows, a flock of sheep, riding and work horses, chickens, ducks, and geese. I don't remember pigs, but there was a building referred to as a pig shed, so I suppose there were pigs at one time. My grandfather also added a third floor and a front porch that wrapped around three sides of the farmhouse; this porch was later enclosed with 54 plate-glass windows. The farm was also one of the first to receive telephone service. I think the original phone number was Berwyn 3. As more houses were added the number became 13, then 613, then 0613. My grandparents also had the second automobile in the area, as I recall. David and Ruth Anna had five children, the eldest being my father, William West Wilson, who was born in 1884. His siblings were Emma Jane Wilson, born in 1886; Winfield Scott Wilson, born in 1889; Rebecca Thomas Wilson, born in 1891; and Elizabeth West Wilson, born in 1895. Being the oldest, my father was put on a pedestal by his mother and siblings. As he grew older, much of the family business was placed in his hands. When World War I began, farm help was no longer available and the Guernsey cows had to be sold. After my grandfather, David Wilson, died in 1925, his widow Ruth Anna ran Elda Farm with the help of only two old men. During this time, my father drove up to the farm almost every evening from our home in Bridgeport to check in on my grandmother. She died in 1929, right around the time of the great stock market crash. I remember her funeral at Elda Farm, a Quaker funeral with all the cousins and aunts and uncles gathered. I played with my cousin Richard outside. Grandmother left a list of specific items to be passed on to each of her five children. Shortly after her death, my father and his brother and three sisters went through the house, room by room and divided up the rest of her possessions, rotating the order of selection according to instructions she had left in her will. The sisters each received a sum of money. My father and his brother Winfield - Uncle Windy - inherited the farm.

My father, William West Wilson, was a civil engineer. After graduating from Swarthmore College in 1904, he worked on engineering projects in many places around eastern United States. He was building the tunnel under the East River in New York City for the Pennsylvania Railroad when he met his future wife - my mother - Marie LaVake. They married in 1911 and had four children: William West, Jr. (Billy), Ruthanna, David, and Conrad. Realizing that his engineering work was hard on his wife and growing family, he and my mother, now with three children, settled in Bridgeport, where I was born in 1920. Father shifted careers and took a position at a bank in Norristown. I think it had been planned all along that Father would take over the farm. Uncle Windy and Aunt Bidda were living in New Jersey, and they spent summers in Vermont with her family. Father still had his job at the bank, but he had lost his entire fortune in the stock market crash - at an uncle's urging he had invested his entire assets in a single company which went bankrupt. Given our strained circumstances, he must have welcomed the opportunity to live at the farm, where we could at least produce our own food. Uncle Windy and his five children visited frequently, and my first cousin, Jim Wilson, worked alongside my brother Dave on the farm off and on for years. While the Wilson family had long been prosperous, suddenly, we were struggling during the Depression. Others in the extended family could go away for vacations to the Poconos, the Jersey shore, or Vermont. For years to come, we would spend our summers working on the farm as my father worked his way out of debt and we lived off the land. The Depression years must have been hard on my father. His job at the bank was extremely demanding. He also worked on the farm. I remember him coming home and changing out of his banker's suit into his work clothes to help get the hay in before a thunderstorm. We grew oats and wheat, alfalfa, timothy, soybeans, and corn. We had two big silos, and haylofts in both barns that the cousins would play in when they came to visit. We had a Ford tractor, but we still used horses - a team of two big, powerful draft horses - for certain jobs.

William West Wilson and Marie Wilson at Elda Farm. We all helped with haying. It was my job to lead the horse that pulled the hay up into the haymow. Someone stood on the haywagon and operated a great metal fork that grabbed a load of hay, which was lifted by a rope onto a rail track over the haymow. I could feel the strain as the horse pulled the rope that lifted the hay fork. Then it went slack when the hay reached the conveyor rail. The person on top would yell, "That's enough" and I'd stop the horse and lead it back for another load. It wasn't a hard job, but you had be kind of agile not to get tramped on by the horses with their huge hooves. We had an enormous vegetable garden, and rows upon rows of gooseberries, currants, raspberries, and blackberries. There was rhubarb, and a great long row of asparagus that had been there for years. There were orchards and flower gardens, too. We put up most of our own fruits and vegetables. There was a root cellar under the carriage house where we stored our potatoes. We also had a room in the basement - a dark room - with shelves from floor to ceiling that was always packed with canned goods for the winter. I remember Mother canning in the summertime. She canned beans and beets and all sorts of vegetables. She put up enough tomatoes to last all year. My brother Dave did barn chores in the morning before school. I had to feed the chickens, but I don't think I ever worked in the barn. We had ten or twelve cows, and a farm manager named Jimmy Danehower. There was also a hired man who spoke with a thick European accent and had six children - maybe more.

Dave loved to work in the barn with the farm hands, and he picked up a lot of their rough speech. Once or twice that language slipped over into the house and

he had his mouth washed out with soap. Dave always wanted to be like other people and tended to adapt his ways to whomever he was associated with. All the while we were growing up he planned to be a farmer. He went to Penn State Agricultural College - with his cousin Jim Wilson - and introduced a number of innovations to Elda Farm, including contour farming and crop rotation. I think we were the first farm in the area to introduce alfalfa. But by that time, following World War II, the taxes were so high that it was no longer profitable to farm. My grandfather had overbuilt. His fancy barns were an extravagance that cost too much to maintain. Most of our farm help had been passed down with the farm as well. Old Al Jacobs had worked at Elda Farm for four generations. His family had been slaves, I suppose, to the Jacobs family, which lived up the valley. [Note 3] Al had worked for my great-great grandfather, David Wilson, Jr. He had started as a boy of ten, carrying the mail and doing little chores for which my great-great-grandfather paid him. When he grew up he went to work full time. After David died he worked for my great-grandfather, and later for my grandfather. Al did some gardening and mowed the lawns with the great horse-drawn mower. He was also my grandfather's coachman. Our family had a horse-drawn station wagon, a fancy enclosed carriage with beveled plate glass windows and velvet seats. You entered it from the back. Inside were two long seats, facing each other. Outside, in front, perched up high, was the coachman's seat. The coach was used for taking family members to the train, or sometimes to the store. Al Jacobs was old and losing his sight when we moved to the farm in 1930. He continued caring for the lawns as long as he was able to. Then my father set him up with a pension in the little house where he lived with his wife Debbie and his daughter Reba. Hobos were very common during those Depression years. They were homeless men riding the rails and traveling the roads on foot, going from farm to farm begging for food. I heard somewhere that they used to leave a stone marker of some sort to signal a family that would take them in. They stopped regularly at our place. Mother never turned away anyone who was hungry. Sometimes they would offer to do some work for food, and Mother would find chores for them to do - even emptying the garbage. Sometimes they would sleep overnight in the barn. Father and Mother would warn them not to smoke, because of the danger of fire. I remember once a man came at dinner time. Ida Shine was with us, an older woman who had worked for us, helping in the kitchen, since we lived in Bridgeport. Ida let the man in and fed him in the kitchen while we ate in the dining room. He sat there, talking a blue streak about how glad he was to get back into some real country after being upcountry with those stingy Quakers. And Ida put her hands on her hips and said, "I'll have you know you're in a Quaker household right now." One relative of ours who was famously generous was my father's cousin Billy Walker. He had a meat market below King of Prussia. It's said that he fed most of Bridgeport during the Depression years with free milk and meat. Many people came to our farm for milk. We always had a surplus. We gave away baskets of fruits as well, or let people go out and pick over the orchards. As the economy rebounded after World War II, reliance on the farm waned. My brother Dave gave up farming and eventually became a science teacher in the Radnor schools. Most of our fields at the farm went fallow and, in 1959, my father and Uncle Windy sold the property. The era of Elda Farm ended.

Conrad Wilson, a genealogist and historian, worked during the 1960s and 70s at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia and at the Chester County Historical Society, where he served as director. He also taught local history at Conestoga High School in Berwyn for several years in the 1960s. In 1985 he and his wife moved from Pennsylvania to Dummerston, Vermont where he currently resides. His son, Alex Wilson, also of Dummerston, assisted him with this article.

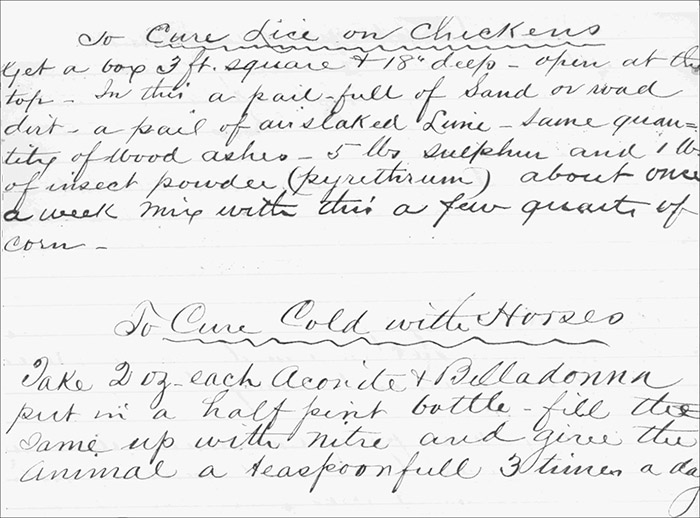

This handwritten excerpt appears to be from a farm journal or handbook used at Elda Farm. It was included with the photographs from a Wilson family descendant used in this article. It's not too difficult to imagine curing horses with colds - but chickens with lice is another matter. |

||||||||||||||