|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 43 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Winter 2006 Volume 43 Number 1, Pages 10–26 GREAT VALLEY AREA LIMESTONE QUARRIES

Editor's note – Part 1 of this 3-part series about Great Valley area limestone quarries was about the Howellville quarries and was published in the Summer 2005 issue of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly. Part 2 was about the Cedar Hollow quarries and was published in the Fall 2005 issue of the Quarterly. As they drive along the eastern edge of Valley Forge National Historical Park on the busy Route 422 expressway and its intersection with Route 23, few people realize the area here between the park Welcome Center and the Schuylkill River was once the thriving industrial village of Port Kennedy where the main business was quarrying limestone and shipping lime. Today all that remains is the Italianate Style Kennedy-Supplee mansion, the First Presbyterian church, a railroad station, and a few old houses. As one travels or walks through the eastern half of the park along County Line Road, the rolling hills and open fields hide an area where there were once many old quarries and buildings.

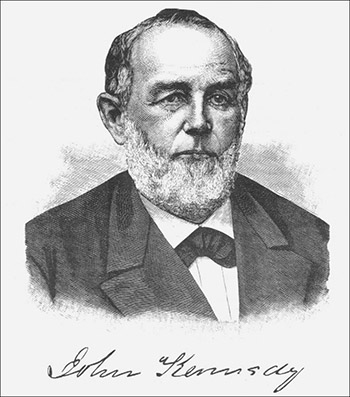

Before the Revolutionary War—and for several decades after that—the landholders in this area were farmers. A major landholder, Mordecai Moore, sold his farmland here along the Schuylkill River in 1803 to Alexander Kennedy, who had come to America from Ireland in the early 1790s. Alexander realized that his 128-acre farm had extensive areas of limestone. The use of lime to fertilize the soil was known and Alexander constructed small kilns to extract lime for himself and his neighboring farmers. The area was called Kennedy Hollow. Alexander died in 1824 at the age of 63 and is interred in the cemetery at Great Valley Presbyterian Church. He died without a will and his wife, Margaret, sold the Kennedy farm to David Zook, already a successful lime merchant. Alexander's youngest surviving son, John, was not yet 10 years old when his father died. He eventually grew to have many interests, but his greatest impact was as the force behind the growth and early prosperity of what eventually became Port Kennedy. The Schuylkill River Navigation had been chartered in 1815 to bring anthracite coal to Philadelphia from Port Clinton, an area above Pottsville, Pennsylvania. Bulk cargo traveling south on this route could then connect with New York harbor via the Delaware River and the Delaware and Raritan Canal in New Jersey. The Schuylkill River rose 588 feet and 92 lift locks were constructed along the side of the river—along with dams built across the river in conjunction with the locks—to make it navigable. The 108-mile waterway was completed in 1827 and had its most prosperous decade in the 1850s. Two of the area locks may be seen today: lock 60 at Mont Clare near the bridge over the Schuylkill at Phoenixville and the canal tow path in Manayunk. The canal period was brief as the growth of railroads quickly overtook them as the most economical means of shipping goods and moving passengers. The Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, whose tracks along the west, or south, bank of the Schuylkill River ran right by Kennedy Hollow, was completed around 1841. It was the railroad that then brought the coal from northern Pennsylvania—coal that, instead of wood, could now be used as a substitute for the charcoal as the fuel in the lime burning process of the kilns.

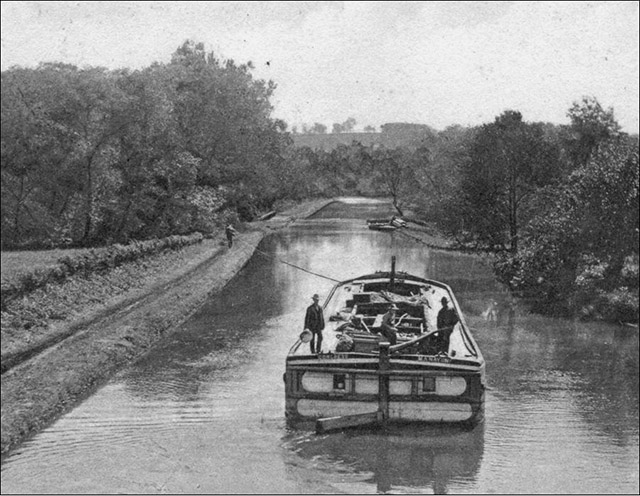

Postcard of a Schuylkill Navigation bulk cargo barge at Parker Ford, north of Phoenixville. This is thought to be the type of barge used for shipping lime. The name Congress is legible on the stern to the left of the rudder and the name Manayunk to the right. The postcard was mailed in 1908. Courtesy Herb Fry. John Kennedy must have quickly realized that with the ability to use the river to ship lime products from his quarries he could expand his business. He built a landing and wharves along the river and after that the name of the village was Port Kennedy. Kennedy shipped lime in large commodity barges that used the canal and in schooners on the river. A rail spur connected his quarries with the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad near the Port Kennedy landing. Today, the western part of the track bed of this now abandoned rail spur is the eastern section of County Line Road through the park. The earliest maps of the Port Kennedy area are:

The 1840 U.S. census, in addition to reporting the number of persons in a household, included questions about persons engaged in mining, agriculture, commerce, manufacturers and trades, the navigation of canals, lakes, and rivers, and learned professions and engineers. It lists 6 lime burners or lime dealers in Port Kennedy: Andrew Blair & Co.; Mrs. Violetta, widow of Robinson Kennedy; Messers. Hunter and Roberts; David Zook; John Kennedy; and David R. Kennedy, John's older brother. The census also reported that Port Kennedy produced lime in value of over $150,000. John Kennedy was the most extensive lime dealer in Port Kennedy. In 1842 he bought the lime works which he managed for the next 35 years. By 1858 he had 14 bank-style kilns—built into the side of a hill—not far from the village. The largest produced as much as 2,500 bushels. He employed 60 to 70 men and almost all of them were Irish immigrants. He is said to have been very kind to his employees.

Above: Exterior view from the southwest showing the south front and the west side of John Kennedy's Italianate Style mansion Kenhurst. HABS PA,46-POKEN, 1-1. Below: Detail of the plaster ceiling of the east room (drawing room) on the 1st floor of Kenhurst. HABS PA, 46-POKEN, 1-24. Both photographs taken October 1982 by Jack E. Boucher. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey.

Kennedy also built his elegant Victorian Italianate Style mansion, “Kenhurst,” in 1852 on a high point in the village overlooking the river and demonstrated the use of lime to make plaster with elaborate plaster ceilings. “Kenhurst” was thought of as the “big house” in the middle of an industrial village rather than as a country residence and is today's Kennedy-Supplee Mansion. He later was an Upper Merion Township school director, president of the Farmers' and Mechanics' Bank of Phoenixville, and president of the Montgomery Agricultural Society. He died in 1877 at the age of 61 leaving an estate valued at $100,000. The First Presbyterian Church was organized in 1845 mostly by members of the Great Valley Presbyterian Church on Swedesford Road in Tredyffrin Township. It was a mission of the Lower Providence Presbyterian Church until 1873 and the Reverend Henry S. Rodenbough served both churches for 27 years. The Lower Providence and Port Kennedy churches were on opposite sides of the Schuylkill River and a bridge was needed both for the reverend and to connect the villages of Betzwood and Port Kennedy. On March 9, 1846 the Port Kennedy Bridge Company was incorporated by an act of the Pennsylvania Assembly. William Wetherill of Audubon was the president of the bridge commission, Isaac Walker was the treasurer, and John Kennedy, his brother, William, and David Zook were on the board of managers. Until the bridge was built people were ferried across the river in flat boats. The first Betzwood bridge, a long covered bridge wide enough to allow 2 wagon to pass, was completed by the end of 1849. It was a toll bridge until 1886. The Port Kennedy side of the bridge also crossed over the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad tracks. A December 1901 flood and ice jam knocked down 2 of the bridge's 3 stone piers and some of the bridge was swept away. Montgomery County appropriated $26,000 to build an iron bridge in the same location. As traffic increased, this bridge, over the years, was replaced with several another bridges. The Betzwood bridge was closed to automobile traffic in 1991 because of structural deterioration but continued to be used by bicyclists and hikers until December 1992. It was imploded by the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation in June 1995. A new bridge was built for the new Route 422 expressway. The remains of the 3 support piers in the river and the old bridge approaches from the side of the river can still be seen. Today there is talk of rebuilding a new bridge in the location of the old bridge to relieve some of the traffic on Route 422. In 1846 a large cavern was found during a quarrying operation in the Port Kennedy area. Sweeney-Justice (p. 7) quotes a Philadelphia Public Ledger article that it was said to be 160 feet long, 60 feet wide, and 20 to 40 feet deep. It had many stalactites that formed arches and was so large that an audience of several hundred people attended a concert of the Great Valley Brass Band in one of its chambers on July 4th of both 1846 and 1847. Concertgoers traveled from Norristown by steamboat. Its walls were later quarried away and its location is lost to posterity. Woodman, in describing his visit to Port Kennedy in 1850, provides the earliest and most extensive picture of the lime business there (pp. 130-132). There is now (1850) ... more than fifty houses, sixty lime kilns in constant operation, employing more than four hundred men; a large hotel, three stories high and forty feet square; four stores, two blacksmith shops and wheelwright shops; and numerous other manufacturing trades carried on at the place; and two lumber yards and several coal yards. ... Port Kennedy ... is celebrated for the great quantity of lime that is burnt, and shipped in canal boats annually from there to various parts of the states of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Delaware and Maryland. The amount sent from this place during last year, I was informed by two of the proprietors, was more than one million, two hun- dred and fifty thousand bushels. We may then safely hazard the opinion that it is the most extensive opera- tion, in that line of business, in the Union. Here ... may be seen the jolly sons of Emerald Isle, some driving their carts loaded with lime and coal, to and from the river, some hauling stones to fill the kilns, others are quarry- ing, some engaged in filling, while others are loading carts, and, in fact, all the different operations ... are conducted at the same time, at different kilns, belonging to the same person. ... The boats that carry the lime from the place are large and commodious, and of late most of them are furnished with masts and sails to be used in tide-water. They generally contain about three thousand bushels. The limestone lies near the surface, and is easily quar- ried. There are two hills of considerable elevation ... which are a solid body of limestone. A small vale of about sixty feet in width passes between them, and gradually descends toward the river, which is the great thoroughfare for the numerous teams employed in conducting the business. ... In some places roads or cartways have been cut through solid bodies of limestone and lead to quarries belonging to different persons, one of which I lately examined. It had then a base line on a level with the causeway, of about one hundred and thirteen feet. Its perpendicular height was about eighty feet, and it extended in length more than two hundred feet. This quarry is owned by David Zook. ... A public road now passes through this prop- erty, between these low hills, and leads from Port Kennedy, through a part of the old encampment, to the Gulf Road. The lime kilns are erected at various places – some on the river, others on both sides of the road just mentioned, generally from six to twelve abreast, and containing from two to three thousand bushels. ... Several large basins have been excava- ted on the river, for the purpose of boats entering to receive and discharge their cargoes, and there are also a few docks for boats to enter. The greater part of the business of the place is done through the medium of the canal. Coal and lumber are brought in. ... Little business is done here, or at any other place on the river by the Reading Rail- road, when the navigation is open, except that the mail is transported ... and a passenger train stops daily at this place. There is a postoffice also established here.

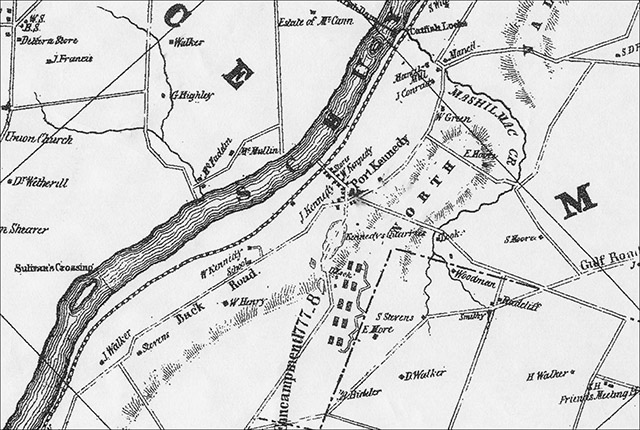

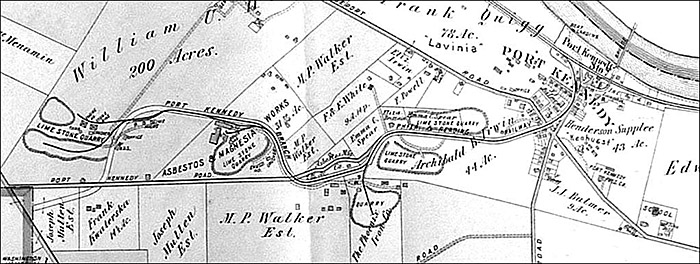

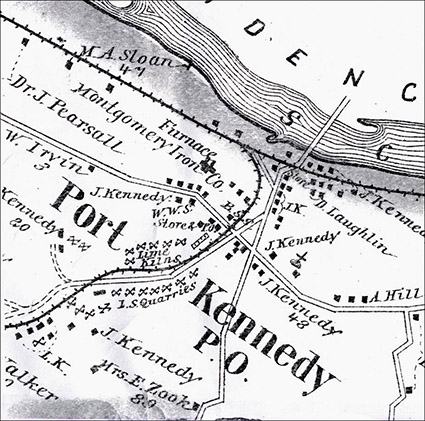

Port Kennedy in 1849. This earliest map of the village is part of the 1849 Map of Montgomery County Pennsylvania. The railroad, the properties of J. Kennedy and W. Kennedy, a store, Kennedy's quarries, the Zook property, Gulf Road, Back Road (now Route 23), and encampment buildings can all be seen. Sweeny-Justice provides more details in describing Port Kennedy at the time of the 1850 U.S. census as a busy place (pp. 8, 10). The quarries and canal boats, railroads and bridges meant business, and the village continued to grow. Four hundred and forty-seven people were listed as living in the village proper . . . and that number did not Include farming families like the Zooks, who ... lived just outside the defining lines of the village itself. . . . Of the population counted, 196 were women, 184 were children under the age of 16, three were over sixty-five years old, and eight were African-American. The majority of the names were Irish: Kennedy, Kelly, McMullen, McLane, Horton, McAllister, Collins, Mahoney, McKenny, etc. . . . There were eighty-six laborers, thirty-one quar- rymen, ten boatmen, seven limeburners, four clerks, three lime merchants, three blacksmiths, two engineers, two shoemakers, two masons, and two butchers, plus a hotel keeper, bartender, coal merchant, carpenter, toll collector, merchant, wheelwright and tailor, but only three farmers. Today's white stone building at the point where Route 23 and County Line Road meet in the eastern edge of the park was a quarry weighing station and was probably constructed between 1830 and 1840 on the site of an earlier log house and barn. According to Sweeny-Justice it was located near the center of town. By the turn of the century it was a residence for the Bird family and is now called “the Commissary Building.” When the building was examined in 1979 no traces of hoists or bases for scales were found (Dodd, vol. 2:117, “Quarry Building”). The Norristown Register and Montgomery Democrat for Tuesday, November 30, 1852 carried a notice of a sale of the limestone land and quarries of David Zook. At Port Kennedy, in Upper Merion Township, the subscriber desirous of relinquishing the Lime business, offers at Private Sale, his Limekilns, quarries and about 13¾ acres of limestone land at Port Kennedy. There are two quarries now open, one of them about 60 feet deep and the other about 40 feet deep, and both may be sunk many feet deeper and drained. The whole height may be increased to over 100 feet, thus furnishing the largest amount of good limestone there is to be found in the County of Montgomery. There are five kilns all in good order, a stone office, two stone dwellings, a frame dwelling and a large frame stable. The whole to be sold together or divided into two lots, the largest of 10½ acres with the largest and deepest Quarry, office and five kilns thereon, and the lot with the residue of improvements contains 3¼ acres. There is a right of road down to the River in connexion with the Kilns and Quarries, a large basin and wharves on the Schuylkill River. The Subscriber has expended a large sum of money in making good roads into his Quarries, in building bridges over the roads about his kilns, and he now offers all for sale, confident that upon examination, this will be found the best in Kennedy's Hollow, for an immediate and profitable business, and where the quantity of lime- stone far exceeds any other single property on the River Schuylkill. For terms apply on the premises to David Zook, August 24, 1852. Theodore Bean reports that when he visited Port Kennedy in 1858 it had 1 hotel, 2 stores, a furnace, a church, schoolhouse, blacksmith, wheelwright, and 42 dwellings. At the time of his visit, 3 schooners, 1 sloop, and 1 canal boat were loading at the Port Kennedy wharf. He notes that the masts on the schooners had to be able to be dismantled so they could pass under the bridges on their way to Philadelphia (vol. 2, pp. 1121-1122). Both Bean and Sweeny-Justice question whether the number of houses in Port Kennedy reported by Bean at his 1858 visit could have supported the 447 residents counted in the 1850 census. They speculate that they must have lived outside the village proper, yet the 1849 map does not show many outlying houses.

The furnace mentioned by Bean was the Montgomery Iron Company built in 1855 by Patterson & Company of Philadelphia. This was another industry in Port Kennedy and was probably established here to take advantage of the nearby limestone which, when added to the iron ore, reacted with its impurities forming flux which could then be removed as slag. It is reported that the furnace produced 12 to 15 tons of pig iron a day. The company first appears on the 1871 map, which locates it along the west side of the rail spur where it met the tracks of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. The furnace was remodeled in 1862 and 1869 and expanded in 1880. Cinderbank—also known as Cinder Bank, Cinder Road, and today's Cinder Lane—appears to have been the company's main “street.” The furnace, the engine house supplying the power for the furnace, and most of the worker's houses all stood here. A furnace office was said to be on the Port Kennedy Road facing Cinderbank at a point from where company operations could be supervised. Zimmerman describes some of the company workers (pp. 132-133): Billy Rankin and Peter Hugh were the furnace engi- neers. Jimmie Mercer, the furnace boss, lived in one of the three duplex houses along Cinder Lane. A descrip- tion of Mercer recalled him with his pipe, “the chamber down but never known to go out. And the stem but an inch in length.” Mercer was a cousin of Professor Henry Mercer who was in charge of the excavation of the Port Kennedy bone cave. Irish was the only language spoken. ... Among the speakers were Benny McMenamin [keeper of the fur- nace], the famous horse trainer of Valley Forge, and Barney McHenry, who snapped cinder and commanded a schooner alternatively, and [Andy] Quigg, the “wee man” who, after working hours might be seen with a game rooster under his coat en route to Abram Bleecher's, who was known to breed roosters with no other purpose but to compare roosters. ... Payday at Port Kennedy was a day to be dreaded, owing to the distributors of black eyes and cracked heads which invariably followed the passing of the pay envelopes. The question of super- iority had to be settled and the championship belt changed hands and waists as often as six times a day. Yet with their reputation for combativeness, it is not on record that Port Kennedyites were often represented in the county criminal courts.

Cinder Lane today. Photography by Joyce A. Post. February 2006. By 1857 the iron company had 30 hands and had erected several dwellings for them along both the north and south sides of Cinder Lane. Several masonry duplexes were probably built in the 1860s and one of them was said to have been an office and warehouse for the company. Several frame dwellings were built in between the duplexes. An 11-unit workers' house was built around 1900. This unit, all of the buildings—including the 3 stone cinderblock structures built for furnace workers and all of the furnace buildings—on the north side of Cinder Lane, and some of the buildings on the south side of Cinder Lane are no longer standing (Dodd, vol. 2:122, “Anthracite Furnace;” vol. 8:607-611, “Ruins: Limestone Quarry Area”). Today you can see 3 of the remaining duplexes on the south side of Cinder Lane. Also, from this area you can walk along what would have been the northern boundary of the company—and observe several old walls—on the cinder track bed of the rail spur out to its junction with the Reading Railroad tracks.

The Reading Railroad tracks may be seen on the left. Joining the railroad at this point is the track bed of the old rail spur coming in from the right. The white building In the distance is the Port Kennedy railroad station. Beyond that are two bridges over the tracks. The slanting bridge is what is left of the approach to the old bridge to Betzwood. Beyond that is today's Route 422 bridge. Photograph by Joyce A. Post. February 2006. Port Kennedy's first school was established in 1858. It was located east of the church and was called the Evergreen School because it stood in a grove of pine trees. It was a 2 story, 2 room structure, and grades 1 through 10 were taught here. Another school, called the Port Kennedy School, was built nearby of brick in 1912 and had 4 classrooms on one floor for grades 9 and 10. The Evergreen school building was damaged by a 1923 tornado that damaged other buildings and homes in the village and was abandoned in 1927. The Port Kennedy School was closed in 1930, reopened in 1931, closed again in 1953—it had 120 students at that time, reopened again in 1956, and closed permanently as a school in 1960. Today it is an office building at 1030 Old Valley Forge Road on the east side of Route 422. In addition to shipping lime downriver, it was also shipped 6 miles upriver to the Phoenix Iron Company in Phoenixville. The 1893 map is the earliest map showing a quarry on the south side of County Line Road on land owned by Phoenix Iron Company. This is thought to be the same quarry Buck describes in 1859 in his section on Port Kennedy (p. 47): Reeves, Buck & Co. have recently purchased a tract of land here, and keep a large number of men engaged in quarrying, hauling and boating the stone for the use of their extensive furnaces at Phoenixville, six miles distant. This is also the quarry used for the future park amphitheater.

The rail spur to the quarries was incorporated in 1859 by an act of the Pennsylvania Assembly. By now the quarries extended over a long area in a southwest direction from Port Kennedy. Many of them were at the far end of the line in an area called Cedar Hill. A 5 mile railroad was planned to link all the quarries, the lime kilns, and, later, the waste piles along the way to the river and the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. There were no provisions for passengers. David Zook, John Kennedy, and David R. Kennedy were among the commissioners for the railroad. The capital stock of the Port Kennedy Railroad Company was $150,000 and the Phoenix Iron Company was a major shareholder.

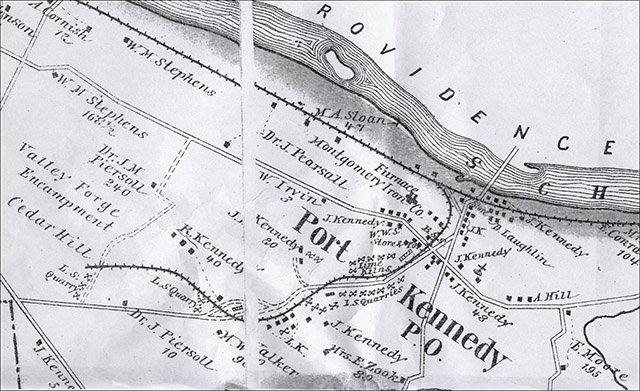

This map of Port Kennedy in 1877 is part Plates 100-101 of the Combined Atlas Map of Montgomery County Pennsylvania. The rail spur branches off the Reading Railroad tracks and curves past all the quarries and kilns out to the westernmost quarries in the Cedar Hill area. Many symbols of what appear to be crossed pickaxes along the spur represent quarries and kilns. The Montgomery Iron Co. is seen at the junction of the spur and tracks. The Zook property and the encanpment area are also shown.

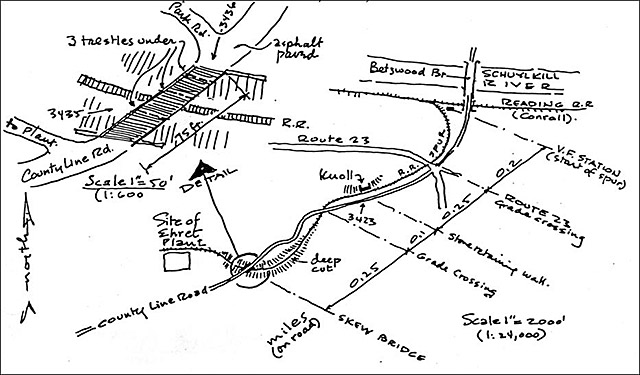

The inset in the upper left corner of this 1979 drawing shows the earlier trestle bridge area over the rail spur cut. Today the area looks like part of County Line Road, but the careful driver can determine the exact location of this spot. The location of the Ehret plant is shown near the lower left corner. It was not built until 1895 and was mostly razed by the time of this drawing. Several other rail cuts are also shown. John and Cherry Dodd. List of Classified Structures Reports. Valley Forge National Historical Park, 1979. Vol. 8:4860, 703, “Port Kennedy Railroad Spur.” The charter stipulated that the railroad's shipping charge could be no more than $.60 a mile. The track was standard railroad gauge. It had 3 grade crossings and one 75-foot timber trestle-type bridge over one of the railroad cuts along the way. Several of these cuts can still be seen near the stretch of County Line Road in the former bridge area. One report states that the total length of the rail spur was 1.3 miles. Dodd gives original dates of 1848 to 1871 for the rail spur and the name of Quarry Road, so it is thought that perhaps sections of the rail spur existed before the act of 1859 (Dodd, vol. 8:4860, 703, “Port Kennedy Railroad Spur”).

Above: Postcard showing the 3-story Port Kennedy Hotel and the 1910 railroad

station along the Reading railroad tracks. This station has not been moved and

is the same site of today's station. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs

Division, Historic American Buildings Survey, HABS PA,46-VALFO.V,2-67.

Daniel Loughin's 3-story Port Kennedy Hotel is first mentioned in the 1850 census and in Bean's 1858 account of his trip to Port Kennedy. It sat on the riverbank along the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad tracks and across the main road in the village from the combined passenger and freight station. The station was built in 1910 and is said to have replaced an earlier station built between 1879 and 1884 that was located on the river side of the railroad tracks (Sweeny-Justice, p. 18). Passenger service was discontinued in 1980. The station is still standing in its original 1910 location and the sign on the station still says “Valley Forge Park.” Loughin had come to Pennsylvania as a youth from Ireland. He originally settled in the western part of the state but came to Port Kennedy in 1847 by stagecoach and canal boat, having been attracted by the industrial nature of the town. The Loughins were the most influential family in Port Kennedy after the Kennedys. They did not have the financial and commercial influence of the Kennedys, but they ran the village hotel, a general store, a coal yard, and rented out all the dwellings. Another village general store was operated by Moore Kennedy, a son of John Kennedy. The Port Kennedy Post Office was established on August 8, 1846 and the first postmaster was Joseph B. Powell. Alex Loughin and John Kennedy were later village postmasters. Many of the houses in Port Kennedy were located along the east side of the road between Kennedy's mansion and the railroad station along the river. Some of these are 2 story frame houses built around 1890 and are still standing near the base of the mansion. Their Victorian style is evident in their colorful—though fading—exterior paint schemes. The one closest to the mansion, the Haney House at 880 North County Line Road is the most Victorian and is painted yellow and green at this writing. The small Nichols house at 884 North County Line Road is still standing. Two other houses here have been demolished. The house formerly at 886 North County Line Road was purchased in 1891 by Margaret Jane Andrews and was said to be the village post office and store in the early part of the twentieth century. The house at 890 North County Line Road was owned by Hires Garnett (Dodd, vol. 3:131, “Haney House;” vol. 3:132, “Nichols House;” vol. 3:133, “Andrews House;” vol. 3:134, “Garnett House”). Toll and Schwager state that in 1919 a country store had been run for many years by Hires Garnett (p. 707).

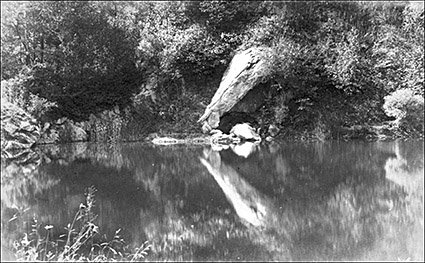

September 23, 1923 photograph of the bone cave found in the Archibald B. Erwin quarry. Tredyffrin Easttown History Club archives. In 1871 workers blasting at the Archibald B. Erwin quarry opened up a sinkhole about thirty feet below the surface where remains of plants and animals from the Late Pleistocene Epoch (~750,000 years ago) were found. Edwin Drinker Cope and Charles Wheatley excavated the site at this time and Cope published his findings in 1871 in the Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. The site was covered over and “lost.” Current thinking is that the sinkhole had opened up, animals and plant matter fell into the hole and were trapped, and then the sinkhole closed. Some of the remains were of large, now extinct, mammals including the mastodon, ground sloth, and saber-toothed tiger. More of the remains were of animals and plants still familiar to us today. No human remains were found. The cave was reopened again in new blasting in the mid 1890s and the remains were rediscovered. This time Dr. Samuel G. Dixon, Curator at the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia, and Dr. Henry C. Mercer, Curator of American and Pre-Historic Archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania Museum spent parts of 1894, 1895, and 1896 examining the remains. Mercer was mainly looking for human remains. Cope also spent some time here again at this time. It was not fully excavated then, either, because of groundwater flooding, and the precise location was again forgotten. Reports of both Cope and Mercer were published in 1899 in the same volume of the Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia. In 2003 Dr. Ted Daeschler made a thorough search of all existing records and maps and compared them with existing conditions in an attempt to find the location. It was concluded to be in an area currently called the “Cave Quarry” by the National Park Service (see the site map at Valley Forge NHP: Asbestos Release Site). The 1912 map is the earliest one showing Archibald B. Erwin—spelled Irwin on this map—as the owner of 44 acres of land on which there were two quarries, one on each side of the rail spur. According to the NPS site map just cited, the “Cave Quarry” is Erwin's quarry on the north side of the rail spur. [His quarry on the south side is thought to now be the park Welcome Center parking lot.] In the summer of 2004 a University of Pennsylvania geophysical survey crew was brought to the park to determine whether the unexcavated portions of the cave were still intact. The results of this study are uncertain about whether the site is acceptable for future excavation (Strategic Plan for Valley Forge National Historical Park ... pp. 16-17).

Toll and Schwager provide a snapshot of life in Port Kennedy in 1888 (p. 713). Daniel Loughin was still in the hotel business, although his daughter, Isabella, was said to be running it. Willis Davis was the hotel bartender. John W. Covington of Port Kennedy was the railroad agent. One of the two physicians in Upper Merion Township, George G. Hartman, lived in Port Kennedy. Joseph Zotnoski and Michael Zielinski were marble quarry workers in Port Kennedy. Marble is metamorphic limestone changed through high temperatures and pressures. When it appears in the Great Valley area, it is on the southern edge of the limestone belt. John Kennedy's sudden death in 1877 had an impact on the prosperity of Port Kennedy. There were other factors too. Cement—which uses lime—became a more important product. The Kennedy family went bankrupt. The Montgomery Iron Company went out of business in 1893. By the early 1900s new equipment was available for making lime, as well as new methods of transportation and new uses for limestone. Crushed limestone was now in demand for road building. Other quarry owners in the Port Kennedy area continued digging out their quarries. Two of

1912 Mueller map of Port Kennedy showing Archibald B. Erwin's—spelled Irwin here—2 quarries, The Phoenix Iron Co. quarry, Ehret's asbestos magnesia works, and the westernmost quarries in Cedar Hill. The Montgomery Iron Co. is gone but the buildings along both sides of Cinder Lane still stand. The boat landing is shown on the other side of the railroad tracks a bit upriver from the bridge and the center of town. The Evergreen school is in the lower right corner and is beyond “Kenhurst” and the Presbyterian church and quite a ways away from the main part of town. them were I. Heston Todd, whose quarries and kilns were west of Port Kennedy on land he purchased in 1872, and who later was an influential person in the early days of the park, and John Robb & Co., operator of quarries to the west in the Cedar Hill area at the far end of the rail spur. Today these westernmost quarry areas are used for park maintenance offices and vehicles and access to most of them is restricted.

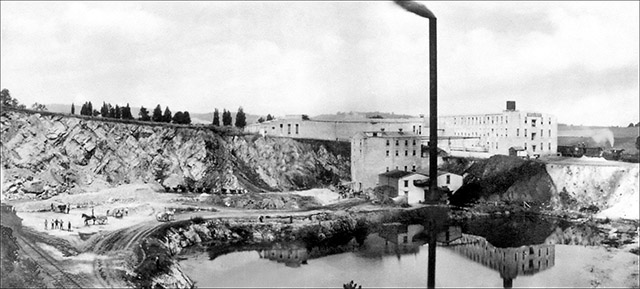

This c.1910 photograph of the Ehret Magnesia Manufacturing Co. has not been published before. Rail cars can be seen on the rail spur at the right and quarry tracks and cars and horses and wagons are at the left. The long 3-story building toward the right is the original 1895 main building. Other associated plant buildings are shown. Courtesy of Valley Forge National Historical Park. The manufacture of magnesia products was another use for the dolomitic limestone of the Great Valley. This is calcium magnesium carbonate, not the calcium carbonate of normal limestone. Between the time of John Kennedy's death in 1877 and the construction of their first buildings in 1895, the Ehret Magnesia Manufacturing Company started buying up and consolidating many of the smaller Port Kennedy quarries. An early vice-president of Ehret was Russell E. Crawford (d. 1965) of Norristown. Bean states that the magnesium content—carbonate of magnesia—of Port Kennedy limestone was as high as 42% (vol. 1, p. 26)—very high. Asbestos is a naturally occurring mineral silicate with strong white fibers. The insulating and flame retardant qualities of asbestos were known as far back as ancient Rome and by the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 1800s, asbestos was used in the manufacture of thousands of products. By the 1970s the health hazards of asbestos had become known. This was what Ehret was manufacturing in Valley Forge. They specialized in what were called 85% magnesia products—insulating pipe covers, insulating blocks, and felt fiber. The 85% was the magnesia; the other 15% was the mineral silicates—the stuff that causes asbestosis and mesothelioma. Over the course of its 80-year history in Valley Forge, Ehret built 20 buildings.

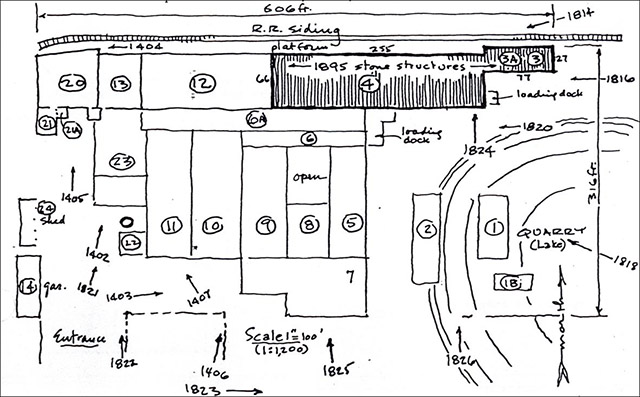

Most of the buildings on this diagram were razed by the time of this 1979 drawing. John and Cherry Dodd. List of Classified Structures Reports. Valley Forge National Historical Park, 1979. Vol. 8:612, “Ehret Magnesia Manufacturing Company Plant.” The original 1895 buildings were stone with reinforced concrete to handle the heavy machinery inside. Building no. 4 on the diagram was the oldest, the largest, and the most striking. With its 3 floors and long façade facing the rail spur tracks it had the look of a typical mill building of the Industrial Revolution and was built by Walter F. Ballinger, a noted Philadelphia architect specializing in industrial buildings (see Philadelphia Architects and Buildings). The second floor of building 4 was where most of the work of making the insulating pipes and blocks was carried out. Here were drying kilns, steel decks and rails for carts, conveyor belts and rollers, band saws for trimming the ends of pipes and blocks, a metal shed for dust control, and tracks and gates for sorting, packing into cartons, and stenciling labels on packages. The first floor had a partitioned office area at the east end and conveyor rollers for moving cartons to the railroad platform. The third floor had a large dust collecting system, a freight elevator, and space for storing finished and packaged products. The cellar was also used for storage and had a chute from the railroad platform. Building nos. 3 and 3A on the diagram are also from the earliest part of the plant (Dodd, vol. 8:612, “Ehret Magnesia Manufacturing Company Plant”). Treese describes the ongoing conflicts between the Valley Forge Park Commission, which was buying up land in an effort to expand the park, and Ehret, which was trying to enlarge its operations at a time of rapid U.S. industrial growth (p. 78). During World War I Ehret was manufacturing insulation products the U.S. Navy needed at the same time the park was planning to acquire—by demolition—land on which plant workers' houses stood. The commission delayed its plans in support of the war effort. After the war, Ehret planned to spend $100,000 to build new workers' housing and make other improvements to its plant site next to the park. Ehret refused to cooperate when the park commission resumed its demolition of workers' houses and the commission retaliated by declaring Ehret's new proposed housing tract a future part of the park: They said: The contention of the Ehret Magnesia Company that it is being harassed in the operation of its work by the Valley Forge Park Commission is not tenable. It is true that the Commission had taken steps, necessary to protect public interest, which were objected to by the company, but the Commission feels that the interests of the public are paramount to the interest of the Company (Treese, p. 78). Around 1920 Ehret added several concrete buildings to the plant site. These are building nos. 12, 20 and 21 on the diagram and were used for the plant engineers and foremen offices (no. 12), railroad shipping and receiving (no. 20), and quality control and a testing laboratory (no. 21). On May 13, 1921, when the Upper Merion tax collector tried to collect delinquent taxes from workmen at Ehret, a riot broke out. Toll and Schwager quote a May 14th report in the Norristown Herald: The riot occurred late in the afternoon at Port Kennedy near the plant of the Ehret Magnesia Company while the tax collec- tor made a request for money. . . . The arrival of constable George Bailey with the tax man evidently made things worse for, when the two attempted to secure the delinquents, a general riot broke out. So many people took part that it was soon evident that the two would be badly beaten. A call was put in for the State Police, who responded from Berwyn on motorcycles. Only the quick response saved the two men from injury. Several arrests were made on the charges of rioting, assault and battery, and making threats (pp. 715-716). Around 1950, metal clad buildings were added to Ehret, bringing a total of 20 to the plant. These were on the western edge of the complex where a completely automated magnesia insulation plant was built and which was later found to be the area of the plant with the highest amount of asbestos waste (building nos.10, 11, and 23 on the diagram). As the company grew, its name was changed to the Baldwin-Hill Company, in 1959 to Baldwin-Ehret-Hill, Inc., and some time in the 1960s or early 1970s it was purchased by the Keene Corporation, a Fortune 500 company. By that time the plant was completely surrounded by land owned by the park. Keene continued manufacturing insulating pipe covers and blocks, felt products, and insulating cement. Between 1925 and the early 1970s Ehret and its successors disposed of waste products from manufacturing operations directly into the Schuylkill River and through a slurry pipeline into several of the inactive limestone quarries.

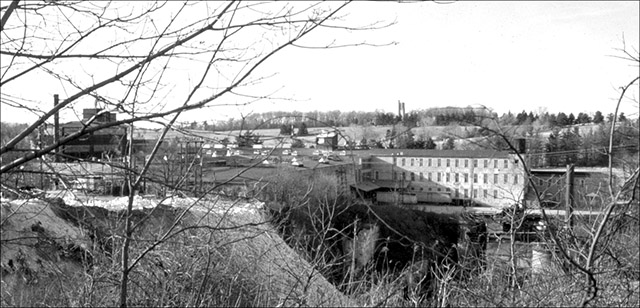

The Keene quarry and magnesia plant c.1974. The original building is on the right . The magnesia insulation plant built in the 1950s is on the left. The Washington Memorial Chapel bell tower is on the hill in the distance. Photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy of R. Toland, Jr.. Unrau reports that in 1975 the U.S. Department of the Interior recommended that the Keene property be purchased and gave an estimated cost of $3,878,450 (p. 559). The plant was closed in 1976 and the rail spur was abandoned. On October 13, 1976 the National Park Service purchased the 46-acre Keene property and the asbestos manufacturing plant. The site had been heavily vandalized and the park razed several of the buildings in 1978. Keene filed for bankruptcy in 1993, having been sued in many thousands of asbestos lawsuits and named in several other related large class-action suits. In 1994 Keene counter-sued in a U.S. Supreme Court case, Keene Corp. v. United States (508 U.S. 200); that case was dismissed. (For a preview of this case see http://justia.us/us/508/200/) On June 12, 1996, Keene announced it was emerging from bankruptcy and reorganizing. In January 1997, while installing underground fiberoptic cable in the amphitheater area, the park discovered asbestos in the soil. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency was brought in and between May and October of 1997 emergency response action was taken to abate immediate risks to public health and the environment in all quarry and related areas. All quarry buildings and structures were demolished and buried and, since these areas were popular with hikers and rock climbers, all access was restricted. Today it is nearly impossible to determine the location of the Ehret/Keene site. If you drive along County Line Road to the point where you can look north across the rolling hills and see the Washington Memorial Chapel bell tower in the distance, the land just to your left in front of you is where it was. Toll and Schwager report that around the turn of the century Loughin's Port Kennedy Hotel was purchased by Hyman Mann, an early Jewish settler in Upper Merion (p. 715). Sweeny-Justice describes the village as a still bustling place in 1908: Three stores—Balmer's, Garnett's and Loughin's—were in business, as were a livery stable and feed store. The United States Post Office shared space in Loughin's Dry Goods and Grocery Store. Gas lamps lined the streets, and it was up to local constable George Bailey to light them. Archibald Erwin had a large quarry operation, and boats continued to move the lime along the river to market (p. 23-24). Also, around this time, Valley Forge Park was a popular tourist destination and it is said that Port Kennedy, with its hotel, was viewed by many as a summer resort (Treese, p. 52; Sweeny-Justice, p. 22). The hotel thrived until it was condemned and razed by the Valley Forge Park Commission in the early 1920s.

In the midst of gradual decline Port Kennedy experienced a brief reprieve between 1912 and 1921. In 1910 Siegmund Lubin, a German-Jewish immigrant who had developed a technically innovative motion picture projector, established a filmmaking enterprise called Lubinville at 20th and Indiana Streets in north Philadelphia. Here he made one-reel silent films and developed film processing knowhow and equipment. He needed more space and in 1912 purchased the 400-acre estate of John F. Betz—a major Philadelphia brewer—called Betzwood, on the opposite side of the Schuylkill River from Port Kennedy. The tracks of the Pennsylvania Railroad ran through the property. Here Lubin built the world's largest state-of-the-art automated film processing laboratory. Some of his technical workers, who processed the film, perforated it, inspected it, and prepared it for shipment, lived in Port Kennedy and crossed the bridge to work. They received at least $5.95 a week, 3 hot meals a day—and the plant was air conditioned! The Betzwood side of the river was also used for film settings and interior shots while the Port Kennedy side was Lubin's back lot. Much of what was going on at the Betzwood Motion Picture Company would have boosted Port Kennedy's economy, from workers processing film, to the hired extras, to the carpenters and other skilled workers building sets, to the animal handlers helping with production. Lubin was one of the earliest pioneers at this time of rapid change in the film industry—silent films were becoming longer with more spectacular scenes and settings. Westerns were very popular. Port Kennedyites of all ages were routinely hired as extras. When a desert scene was needed, lime was spread on the ground. Any regular train between Norristown and Philadelphia on the Pennsylvania Railroad might be attacked by “Indians.” Scenery crews put “Sheriff's Office” and “General Store” signs on Port Kennedy buildings and Loughin's General Store is clearly visible in Sweeter Than Revenge (1915). Hundreds of horses and oxen from the west arrived at the Betzwood station and were marched across the bridge whenever they were needed for scenes filmed in the Port Kennedy area. Live ammunition was used in shootouts and, later, in a Civil War epic. Port Kennedy children loved to cross the bridge to play with the props and mingle with the “real” cowboys, also brought in from the west. Children from the Evergreen School were always sneaking away during filming and the village had to hire a truant officer, Miss McClain. Western facades were constructed at the bottom of Port Kennedy quarries—their rock cliffs resembled western canyons and provided a remote and barren setting.

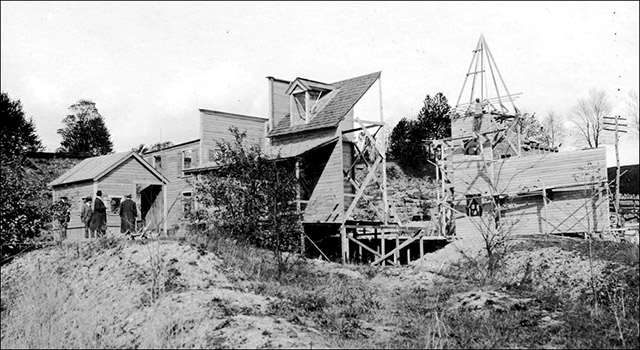

A Port Kennedy quarry was the setting for Through Fire to Fortune or The Sunken Village, a 5-reel 1914 spectacular, filmed by the Betzwood studio. The set was under construction in this autumn 1913 photograph. Courtesy Theater Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia. Spectaculars were ambitious. The 5-reel Through Fire to Fortune or The Sunken Village (1914) called for an entire village to be swallowed up by the sinking of a mine. At a cost of $15,000, a block long platform with houses, stores, and a church was constructed in an abandoned Port Kennedy quarry and, to film the “collapse,” the platform supports were blasted out from under the set and the whole thing fell into the quarry—filming all the while. According to Eckhardt, the film received decidedly mixed reviews. In the 4-reel Battle of Shiloh (1915) fortifications built on the tops of quarries were exploded and filmed as they cascaded down the cliffs. Military personnel from nearby bases were cast as the Union army and arrived for filming at the Port Kennedy station. The Confederate army was played by extras from Port Kennedy and Norristown. Eckhardt estimates Lubin spent about $3,500 a day to shoot this film, and says it received mixed reviews. Between 1920 and 1921 the Betzwood studio made 17 two-reel Toonerville Trolley films—the most successful of all their films. Since 1917 the company had been owned and operated by Wolf Brothers, Inc. of Philadelphia. Since 1908 Fontaine Fox had been drawing his daily and Sunday Toonerville Trolley cartoons and comic strips. They were syndicated in over 300 newspapers and were very popular. The two came together when the Wolf brothers were filming a western on location at the bottom of a Port Kennedy quarry and one of them joked that the little shuttle cars used by the laborers in the quarry looked like Fox's trolley. In both the cartoons and the films the dilapidated trolley was the star, but who could forget the antics of the Skipper, Katrinka, the mule, Aunt Eppie Hogg, and the other regulars. The first film, The Toonerville Trolley That Meets All Trains (September 1920), was filmed on narrow gauge tracks laid down next to the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks on the studio grounds in Betzwood. Eckhardt, a major authority on Lubin and the Betzwood studios, describes the studio's attempt to find a more rustic filming location for the future Toonerville films: For more interesting topography, the studio also planned to use the narrow-gauge tracks of a small mining operation on the slope of Mount Misery on the other side of the river in Valley Forge. But a hair- raising episode soon changed everyone's mind (1992, p. 26). During staging, the trolley brakes failed, they had a runaway trolley on their hands—and the cameramen missed the whole thing. This location proved unsatisfactory. What is fairly certain is that for many of the rest of the Toonerville Trolley films, the producers turned to the scenery along the standard gauge tracks of the Phoenixville, Valley Forge and Strafford Electric Railway running between Valley Forge and Phoenixville. They filmed at the eastern end of the tracks near the no-longer-standing cotton mill that stood at the intersection of today's Route 23 and Route 252 in Valley Forge and at the western end near the no-longer-standing P, VF & S trolley car barns at Williams Corner, southeast of Phoenixville and thought to have been near where today's White Horse Road crosses the north side of Pickering Creek. The P, VF & S didn't operate very often, so during these off hours they made the Toonerville Trolley films. It is said that sometimes both trolleys were on the track at the same time and when that happened, the Toonerville trolley was lifted off to let the “real” trolley go through. It is also said that this Toonerville trolley was stored in the P, VF & S car barns when not in use. In one of the films made in 1921, The Skipper's Flirtation [shown at the 16th annual Betzwood Silent Film Festival, May 13, 2005 at the Montgomery County Community College], the Evergreen School can be seen, as well as a brief glimpse of the newer brick Port Kennedy School. The quality of the Toonerville films was uneven, the novelty wore thin, and, most importantly, they were now competing with the films of Mack Sennett, Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton, and Harold Lloyd. Much speculation exists about the fate of the two trolleys—most people never realized there were two of them. It is said that in 1923, while riding his pony along the Schuylkill River, young Reeves Wetherill found the narrow gauge trolley in the mud and weeds along the bank. He couldn't convince his grandparents, who lived in Mill Grove in Audubon, to store it. It is said that the other trolley—the standard gauge one—was found in a junkyard outside Phoenixville. In 1923 both the Betzwood processing labs and the studio closed for good. By 1918 there were 118 homes in Port Kennedy—most of them for workers. There were also two barbershops—the one owned by Morris Bailey was next to the hotel—and, a little later, a gas station and mechanic's shop, a sadlery and shoe shop, a tailor, a fire company, 2 bands—the Port Kennedy Fife and Drum Corps and the Port Kennedy Cornet Band—and a fraternal lodge.

In 1919, the Valley Forge Park Commission, in an effort to expand the park and improve its main entrance at the eastern edge of the park, received a state appropriation of $250,000 to condemn homes and buildings in Port Kennedy, including sixty homes, the hotel, a store, and the physician's residence. Villagers protested and rioted and found a supporter in Reverend W. Herbert Burk, founder of the Washington Memorial Chapel at Valley Forge. Plans were drawn up to relocate the villagers to a planned community called “East Valley Forge” on the north side of the Schuylkill River—but that never happened. A map of the planned community may be found on pages 32 and 33 of the Sweeeny-Justice booklet. After World War I was over and more funds were appropriated, demolition resumed in 1926. Houses that had been condemned earlier had been lying vacant for years. The tornado on April 5, 1923 had not helped. Eighteen of the old lime kilns were demolished in 1929. Sweeny-Justice quotes a Norristown newspaper at that time reporting that Port Kennedy had taken on “a forlorn and bedraggled appearance” (p. 30).

“Downtown” Port Kennedy in February 2006. Over the next 4 decades more and more of the village was taken for park expansion. The commission condemned more land on May 26, 1937. Port Kennedy land was also needed for the expanding roads and highways on the eastern edge of the park. In January 1946, 5,286 acres in the area belonging to the Reading Railroad along the banks of the Schuylkill River were con-demned. Ten more structures in Port Kennedy were condemned and removed in 1965 to make way for the new 4-lane County Line Expressway—now the busy Route 422 expressway. Port Kennedy officially ceased to exist on October 26, 1973 when the post office was transferred to Norristown. The Andrews and Garnett houses were demolished in 1979. It was the new Route 422 corridor that dealt the final blow to Port Kennedy—dividing what little was left of the village in half and putting the Kennedy-Supplee Mansion on one side of the highway and the First Presbyterian Church on the other.

Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad From Devon to Downingtown and West Chester Embracing Boroughs of Downingtown, Malvern, and West Chester, and Easttown, East Bradford, East Caln, East Goshen, East Whiteland, Newtown, Thornbury, Tredyffrin, Upper Merion, Westtown, West Goshen, West Whiteland, and Willistown Townships. Compiled From Actual Surveys, Official Records and Private Plans by J. M. Lathrop and St. Julian Ogier, Civil Engineers. Under the Direct Supervision and Management of A. H. Mueller, Publisher. Philadelphia: A. H. Mueller, 1912. Plate 4: Part of Upper Merion Township. Atlas of the County of Montgomery and the State of Pennsylvania. From Actual Surveys & Official Records. Compiled & Published by G. M. Hopkins & Co. Philadelphia: G. M. Hopkins, 1871. Bean, Theodore W., ed. History of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1884. 2 vols. Vol. 2, pp. 1121-1122, “Port Kennedy;” vol. 2, pp. 1129-1130, “John Kennedy.” Buck, William J. History of Montgomery County within The Schuylkill Valley: containing Sketches of all the Townships, Boroughs, Villages. ... Norristown, PA: Printed by E. L. Acker, 1859. Combination Atlas Map of Montgomery County Pennsylvania. Compiled, Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys. Philadelphia: J. D. Scott, 1877. Combined Atlases of Montgomery County, 1871, 1877, 1893. Mt. Vernon, IN: Windmill Publications, 1998. Cope, E. D. “Preliminary Report on the Vertebrata Discovered in the Port Kennedy Bone Cave.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 12 (1871), pp. 73-102. ________. “Vertebrate Remains from Port Kennedy Bone Deposit.” Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, vol. 11, pt. 2 (1899), pp. 193-267. Dodd, John and Cherry Dodd. List of Classified Structures Reports. Valley Forge National Historical Park, 1979-1981. 8 vols. Donovan, Frank, J. “The Real Toonerville Trolley.” Railroad Magazine, February 1938. http://www.trainrunners.com/pages/Toonerville%20Trolley.htm. (Accessed February 13, 2006.) Eckhardt, Joseph. “Clatter, Sproing, Clunk, Went the Trolley ... ” Pennsylvania Heritage, vol. 8, no. 3 (Summer 1992), pp. 25-31. ________. The King of Movies: Film Pioneer Siegmund Lubin. Madison, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997. Map of Montgomery County Pennsylvania. From Original Surveys, under the direction of Wm. E. Morris. . . . Smith & Wistar, 1849. Mercer, Henry C. “The Bone Cave at Port Kennedy, Pa. and its Partial Excavation in 1894, 1895 and 1896.” Journal of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, vol. 11, pt. 2 (1899), pp. 269-286. National Canal Museum. The Schuylkill Navigation. http://www.canals.org/education/schuylkill.html. (Accessed February 13, 2006.) Philadelphia Architects and Buildings. “Ehret Magnesia Co.” http://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/image_gallery.cfm/100252. (Accessed February 13, 2006.) Post, Joyce A. “What's in a Picture: Looking at the Details” and “Phoenixville, Valley Forge and Strafford Electric Railway Company.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 3 (Summer 2004), pp. 90-91. Property Atlas of Montgomery County Pennsylvania. Compiled by M. A. Naeff, C. E. from Official Records, Private Plans, Actual Surveys. Philadelphia: J. L. Smith, 1893. Robertson, Jane E. “Betzwood Bridge Comes Down.” Daily Local News, June 14, 1995. Spencer, Kyle York. “A Town Swallowed Up By A Future That Had No Room For Its Past.” The Philadelphia Inquirer, April 23, 1995. Strategic Plan for Valley Forge National Historical Park, October 1, 2005 – September 30, 2008. “NPS Goal ID Number: Ia09, Other Paleo Resources.” pp. 16-17. http://www.nps.gov/applications/parks/vafo/ppdocuments/ACFA741.pdf. (Accessed February 13, 2006.) Sweeny-Justice, Karen. Port Kennedy: A Village in the Shadow of Valley Forge. Gettysburg, PA: Thomas Publications, 1994. This booklet contains many old photographs of Port Kennedy. Toll, Jean Barth and Michael J. Schwager, eds. Montgomery County: The Second Hundred Years. Norristown, PA: Montgomery County Federation of Historical Societies, 1983. 2 vols. Vol. 1, pp. 707-722, “Upper Merion.” Topographical Map of the Revolutionary Camp Ground at Valley Forge Pennsylvania 1906. Philadelphia: Franklin & Clark, 1906. Treese, Lorett. Valley Forge: Making and Remaking a National Symbol. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1995. Unrau, Harlan D. Administrative History of Valley Forge National Historical Park, Pennsylvania. Denver, CO: Denver Service Center, U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1984.

Valley Forge NHP: Asbestos Release Site. http://www.nps.gov/vafo/vafoasbestos/default.htm. (Accessed February 13, 2006.) Woodman, Henry. The History of Valley Forge. Oaks, PA: John U. Francis, 1920. Zimmerman, Deborah L. “Port Kennedy: Prosperity and Decline.” Bulletin of the Historical Society of Montgomery County, vol. 33, no. 2 (Spring 2002), pp. 127-142.

Portrait of John Kennedy. Date unknown. Theodore W. Bean, ed. History of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: Everts & Peck, 1884. 2 vols. Vol. 2, p. 1130. The author wishes to thank the following individuals for additional information, photographs, and sources: Mike Bertram; Robert M. Deger, Historical Society of the Phoenixville Area; Geraldine DuClow, Theater Collection Librarian, Free library of Philadelphia; Joseph P. Eckhardt, Professor of History and originator of the Betzwood Film Archive and Film Festival, Montgomery County Community College; Herb Fry; Scott Houting, Museum Specialist, Valley Forge National Historical Park; Dona M. McDermott, Archivist, Valley Forge National Historical Park; Jeffrey R. McGranahan, Collections Manager, Historical Society of Montgomery County; Paul Marr, Associate Professor of Geography, Shippensburg University; Lance Metz, Historian, National Canal Museum; Roger D. Thorne.

Port Kennedy Bone Cave Remains Many of the animals and all of the plants are still familiar today.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||