|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 3 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: April 1940 Volume 3 Number 2, Pages 31–41 When the Redcoats came marching down the valley into Tredyffrin On the morning of September 16, 1777, Washington drew up his little army on the South Valley hills in East Whiteland township to give battle once more to the invaders but was prevented from engaging by an "equinoctial" storm of unusual violence and duration. The patriot army then withdrew from the high hills to an eminence in the Great Valley near the White Horse tavern (now Planebrook), where it remained in expectation of an attack until four p.m. It then retreated to Yellow (now Chester) Springs, and continued the next day to Warwick Furnace to replenish the damaged ammunition; wet miserable and utterly worn out from incessant marching and countermarching. The Division of Pennsylvania Continentals commanded by Wayne encamped on the farm of Christian Hench, who was an ardent Revolutionist, and supplied their needs as far as it was in his power, even to the slaughter of his herd of cattle. Meanwhile the enemy rested quietly on the hills overlooking the Valley until the rainstorm was over, contenting themselves with ingloriously robbing the hen roosts, smokehouses, barns and houses of the peaceful farmers, and in burning all the fence rails in the vicinity of their campfires. The fences were chiefly of the stake or worm fence type and in all probability the soldiers made shelters of fence rails and blankets in lieu of tents. On the farm of the Dunwoody's, General Mathew's command burned or otherwise destroyed 8,500 rails, notwithstanding the abundance of timber. The officers were largely drawn from the upper class, genteel, arrogant, fleshy from good living, and little actual field service. The men were mostly the riff-raff of Great Britain, Ireland, and Germany. On the 17th, Lord Cornwallis advanced with the right wing to the (Old) Lancaster road and on the 13th continued from Malin's farm past the Warren and Paoli taverns to the Black Bear, where he turned to the left down the Bear Road to Howell's Tavern. The main body of troops marched down the Swedesford Road into Tredyffrin and encamped between Howell's Tavern (now Howellville) and the Old Welsh Line or Baptist Road (now New Centreville). Howe was coiled like a rattlesnake ready to strike, with the most active troops in the rear under the command of Cornwallis, who was the most able general of the British army. Let us visualize the parade: horses and dragoons, the tall-hatted and white-belted grenadiers--shining marks for the backwoodsmen's rifles; the fierce, bewhiskered Hessians, the long files of tawdry-clad infantrymen, the lumbering cannon and the long train of wagons drawn by our own Conestoga horses. Its number has been variously estimated, but probably included fewer than 13,000 men, rank and file, though seemingly endless and long to be remembered by our people. The main body kept to the highway, but the flankers threw down fences and trampled the crops. Like the famous legendary and fabulously huge snake of early Tredyffrin, and immeasurably more dangerous, the hostile army crawled through the beautiful Great Valley. On either side of the well-fenced Swedesford Road appeared the fields of grain stubble, ripening corn and buckwheat, the dark soil of freshly plowed ground, the lush meadows in which small herds of cattle and flocks of sheep pastured; on pact snug well-provisioned farmhouses, barns filled to the rafters with grain and forage, barnyards loud with grunting swine and cackling fowls. The mud was axle deep in the road but there were sparkling brooks in the foreground, and a marvelous background of forest-clad hills in a mosaic of green, gold and crimson foliage. Never before had a British army passed through and desolated a fairer or more bounteous region. To the women and children peering from the attic windows, the drums seemed to repeat and portend "plunder". Following the line of march of the hated enemy came a train of forlorn prisoners closely driven by the Provost Guards under the brutal Major Proctor. In the morning they were drawn up at the road side and there remained until the army had passed and then fell in the rear. In the evening they were marched from rear to near the van, at which time, without the least check from the officers, they endured every kind of abusive and scurrilous remarks. No captive following a Roman triumph suffered more from the jeers of the rabble than those American unfortunates. The English cockney especially had an evil reputation for vile and putrid expressions. As the British army swung slowly through the Valley, soldiers detached themselves singly, or in small squads to forage. A Hessian caught a goose at the Thomas homestead with the remark, "Rebel goose goat for Hesse mans!" East of the Presbyterian meetinghouse dwelt Adam Rickabaugh, whose women folk set out pies and cakes at thehead of the lane as humble peace offering characteristic of the European peasant. A different reception awaited the advance party of the command of General Mathews as it filed into the field on the plantation of Samuel Jones. Some American scouts posted in the forks of a tree on the hill slope (said to have been the same chestnut laterused as a signal tree to the Valley Forge encampment) fired upon and wounded some of the enemy before they were dislodged and driven to the woods, but this appeared to have been the only hostile demonstration.

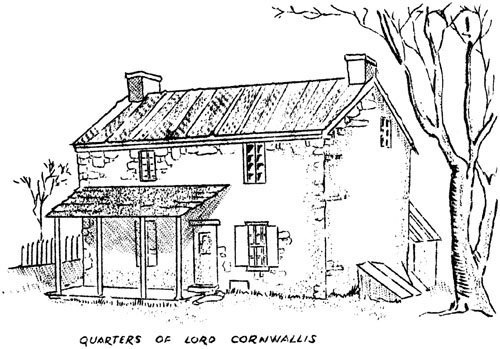

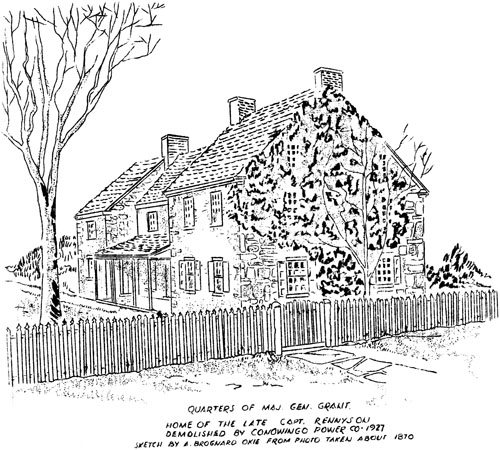

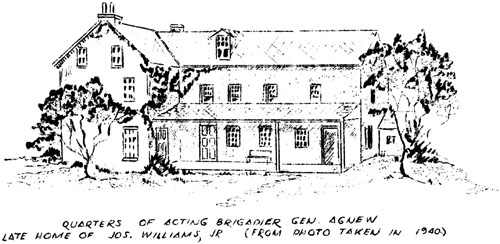

Cockletown Lancaster Road, Camp Tredyffrin Sept. 18th - 21st, 1777 THE BRITISH CAMP IN TREDYFFRIN The British Army encamped from the late afternoon of the 10th to the early morning of the 21st of September, 1777, mainly on the farms of David Howell, Christian Workizer, Valentine Shewalter, Abel Rees, Samuel and James Jones, and Jacob Frick. Nearly all the troops were bivouacked immediately south of the Swedesford road, with the Royal Artillery parked close to the highway near the centre, Brig. Gen, Cleveland in command. The Foot Guards, under Capt. DeWest, occupied the crest of the detached elevation near the rear of the dwelling of Samuel Jones, which was the headquarters of Sir William Howe, and faced the northern slope of the South Valley hills upon which the First and Second Brigades were situated in the midst of the once great apple orchard and nearest to the present town of Berwyn. The regiments were the 5th, 49th, 10th and 4th, the latter the "King's Own" Regiment, and the 40th, 55th, 27th, and 23rd. Brig. Gen. Mathew's quarters was probably at the mouth of the ravine, on the west border of the swamp near the excellent spring in the original Griffith John house, later a tenant house on the Jones plantation. Col. Harcourt and Major Tarleton, with the 16th and 17 th Light Dragoons, were quartered below the Second Brigade and near the headquarters. Brig. Gen. Sir William Erskine and Col. Monckton and the 1st and 2nd Battalions of British Grenadiers, occupied the slope and continuation of the great orchard east of the swamp and ravine. Readers will recall that later at Monmouth, Monckton was slain and his brave Battalion repulsed with slaughter by Wayne immediately after the traitorous Gen. Charles Lee had declared to Washington that American troops could not stand before the British Grenadiers. Opposite the British Grenadiers and near the Swedesford Road on the farms of Jacob Frick and James Jones were the Hessian Grenadiers. Count Donop was soon to fall at Red Bank. West of them was Col. Von Stirn's Brigade of Hessians. One regiment, however, under Col. Von Loo, occupied Wilmington. Knyphausen's quarters were at the James Jones house. Lt. Gen. Wilhelm, Baron Innhausen and Khyphausen commanded the Hessian troops after the departure of Gen. DeHeister. He remained in America until the close of the war. Bodily infirmity and the loss of an eye caused his retirement in 1782, having, as he said, "achieved neither glory or advancement." The Yagers or Amspath Chasseurs, horse and foot, commanded by Lt. Col, VonWurmb, were in a field on the Havard land, the northwest corner of the Baptist and Swedesford Roads, later the site of the Stone Chimney Picket, and were the only troops encamped north of the Swedesford Road. West of the Guard, on advantageous elevations in the Valley, were the Fourth and Third Brigades. Of the former, the 13th Regiment was raised in Ireland, the 46th and 33rd Regiments, and of the latter the 17th, 44th, 42nd and 15th, the last being the Yorkshire Regiment which lost its beloved Lt. Col. Bird in the battle of Germantown. The 64th Regiment was apart and in the rear of the Fourth Brigade. Lord Cornwallis had his quarters at Abel Rees', Major Gen. Grant at Valentine Shewalter's, Lt. Col. Agnew, Acting Brigadier, who was another unfortunate at Germantown, quartered at Christian Workeiser's, and Major Gen. Grey at Howell's Tavern. Gen. James Grant was the same officer who, a Major in Forbe's advance on Fort Duquesne, French and Indian war, by a foolhardy display caused the massacre of his Highlanders and a part of Washington's Virginia Regiment under Major Lewis. The 1st and 2nd Battalions of Light Infantry commanded by Lord Cathcart and Major Maitland were on Quarry Hill near the cedar grove and northwest of the present Bear roadbed.

Quarters of Lord Cornwallis Neither of the original sketches of the camp show the position of the 7th or Royal Fusileers of London, the 28th or Gloucester Foot, the 43rd or Oxfordshire Regiment, if present. Capt. Patrick Ferguson's Independent Rifles and a part of Simcoe's Queen's Rangers were certainly present but not shown on the maps. Ferguson, it will be remembered, invented and his corps used a breech-loading rifle. He ended an eventful life four years later on King's Mountain, where his troops were defeated and captured by an irregular force of bordermen. Andre's sketch of the camp in Tredyffrin places the First and Second Brigades too far west where it is known there was at that time a heavy stand of timber. His map is doubtless far less accurate than that of an engraved, unsigned draught discovered in England fifty years ago by Charles Pennypacker of West Chester. The map shown here is an endeavor to combine the published data, the traditional sites and the cartographer's knowledge of the terrain. The encampment covered approximately seven or eight hundred acres, bounded on the south by the forest on the South Valley hills, and on the north side and parallel with the Swedesford road there was a thin and almost continuous stand of hardwood, mostly hickory. Branches of the Valley Creek and Trout Run provided abundant water for the camp. Videttes (horse pickets) patrolled the contiguous sections of the (Old) Lancaster, Baptist, Yellow Springs and Bear Roads, but apparently no further. A large cattle pen was built on a branch of the Valley Creek as it emerged from VanLeer's (now Prissy's) Hollow. Here the cattle and sheep taken from the farmers was confined and slaughtered for the army. The British Army Quartermaster and Commissary Generals Erskine and Wier swept the neighborhood bare of food for man and beast, despite Howe's proclamation that if the inhabitants remained quietly at home, nothing would be disturbed. Cut off from its base and fleet the Army was compelled to live upon the country, and it lived upon the fat of the land while stuck in the mud of Tredyffrin awaiting the flooded Schuylkill to subside. Some of the farmer's boys, in fear of impressment, "skedaddled". British officers pretended that all the young men of the neighborhood were in the American Army. Nathaniel, a young son of Samuel Jones, drove through the lines to go to the mill and did not return. Attaches of the headquarters amused themselves by repeatedly informing the family: "Well, we caught the young rebel today!" Hector Mullen, a pickaninny belonging to Jones, lived to become the patriarch of a numerous tribe and took great pride in his old age recalling the time he held Howe's war horse in front of the headquarters. It was the proudest event of his life. The General threw him a small English coin which the delighted negro tossed into the air until he failed to make the catch and the coin rolled under the great stone doorstep, lost to him forever. Although Howe's personal desire may have been that of conciliation, his army behaved as if in a conquered country, sweeping the land bare of provisions, forage, and stock, leaving the inhabitants in many instances absolutely destitute. There are many almost forgotten traditions of their depredations. A party of Hessians visited the Jacob Bach (now Baugh) farm and were in the midst of looting and wanton destruction when John, the young son of the owner, voiced his disapproval. A soldier pricked him with a bayonet and kicked him through the kitchen doorway. John's mother was frying doughnuts and was ordered to keep on with her occupation, but she became so enraged that she hit the man over the head with the frying pan filled with hot grease. At the first alarm the two negro slaves were ordered to drive the geese into the woods; they obeyed and then took "leg bail" themselves. The marauders robbed the farm of everything they could haul away, even digging the potatoes. The beds were ripped open in search for money and the goose feathers cast to the wind, and as an additional annoyance the window panes were poked out. Glass being then unobtainable, the windows had to be boarded up until spring and

Quarters of Maj. Gen. Grant, home of the late Capt. Rennyson, demolished by Conowingo Power Co., 1927 sketch by A. Brognard Okie from photo taken about 1870 the family would have fared badly but for the kindness of neighbors. Two deserters were shot and buried under a tree near the quarry on this farm. It has been said that the Hessian hirelings had been promised the lands and chattels of the Rebels whom they were to dispossess. Many were eager for plunder and made no distinction between Whig and Tory. Until recently there had been a large jagged hole in the stair door and several lead slugs in a stair riser of the house formerly occupied by Benjamin Jones, but now a tenant house on the Brookmead Farm. There is a tradition to the effect that a Hessian thought he saw a Rebel soldier in the kitchen and fired a shot through the window. The Hessians would sneak out of camp without their muskets and visit the nearby Quaker farmhouses in search of plunder. A typical instance is that of a small party at Rehobeth farm. They first drank all the milk and cream in the springhouse and without pausing to wipe the cream from their beards continued to the house in search of something to eat or to carry away. The Walkers called them "unwelcome visitors". Woodman and others relate that when three Hessians approached the Stephen's house there were several visitors present, seated outside around the front door, enough to have prevented the looters from entering, yet all but the owner and his young son fled, among them Chaplain William Rogers, a Baptist parson belonging to Mifflin's Division, who ran into the house, divested himself of his military coat and gold watch, which he gave to Sarah Stephens and hid himself under an empty hogshead in the cellar. Sarah locked his timepiece in a bureau drawer and hid his coat outside under a bush. When the soldiers arrived, one of them seized Abijah by the collar, presented a dagger at his throat and relieved him of his watch. They then entered the house, shook hands with the aged grandmother who had suffered a paralytic stroke and was tied in her chair. They called her "Mutter" before ascending the stairs to break open the drawers, chests, and cupboards to take whatever they considered of sufficient value and among the very first objects was the Chaplain's valuable gold watch. Meanwhile the family availed themselves of the opportunity to place the silver spoons and some other small objects of value into the old lady's pockets, feeling that the respect they paid her would insure her from search. When they came down the poor old dame fumbled the silver in her pockets and chattered, "Prissy, does thee think the spoons are safe?" Fortunately the aliens did not understand English well enough to comprehend, so the spoons were saved. A large detail of British approached the Stephens home and halted while the officer in charge inquired the location of the farmhouse of Thomas Waters (who was the father-in-law of Col. Dewees toward whom they seemed to nurse a particular grudge). Sarah Stephens once more proved disloyal to a neighbor and fellow countryman, for she pointed to the next farm, which they proceeded to loot of over 173 pounds worth of personal property including a substantial amount of cash in gold, silver, and paper. The Waters' were peculiarly unfortunate. A bag containing 55 pounds in gold and silver had been hastily thrown under an outbuilding where it would have been safe had not a soldier chased and cornered a particularly fussy old hen under the same structure. Of course, he found and seized the bag for his own good fortune. They also took a servant who had thirteen months to serve, to the value of fourteen pounds.

"in account of a Sacrilige Comited in the Baptist Meetinghouse:

Tredyffrin x x x by some of the British army, x x when sd Meetinghouse

was Broke open & was Stole from thence the sacramental Dishes,

viz; 2 pewter Dishes 0.15, 2 do. pints 0.8. 1 Diaper Table Cloth

0.12. 1 Bible of the English Language 0.15. A Change of Raiment

for the administration of Baptism viz 2 Linen Shirts 0.16. 2 pr.

Linen Drawers 0.10. the Lock of the Chest the Good were in 0.5.

The Saxtons tools for Burrials: 1 Grubing hoe 8/ 1 Spade 7/8 -

0.15.8. They Destroyed and Burnt on the Parsonage farm viz: 195

Pennell of Fence Equl to 810 Rails at 4/ pr. Hundred 1.12.4,

6.8.10. It is a pleasure to record a single act of courtesy. Some Hessians had halted the wife of Whitehead Weatherby as she was riding out ostensibly to the grist mill with a bag of wheat, but actually to carry provisions to her husband who was watching the British camp from a vantage point in the South Valley Hills near Cockletown. The Hessians were about to rob her of her jewelry when a gentlemanly British officer rode up to her rescue and conducted her safely home to Grove Hall in Easttown. THE BRITISH FORAY ON VALLEY FORGE Valley Forge appeared as a notch in the North Valley Hills plainly visible from the British camp and loss than three miles distant, yet unvisited by the military until the day before their departure from Tredyffrin. There was then no road through the length of the gap. William Dewees was the well-to-do iron master whom the Quakers accused of being aristocratic. He had been a colonel of militia but was attached to the quartermaster's department during the Pennsylvania campaign and when that department began the delivery of army supplies at his place, he entered protest that it was directly in the path of the enemy and if discovered by them it would cause his ruin. Nevertheless, as wagon after wagon arrived, his mill and storehouses became stocked with military stores. On September 13, a British spy discovered, as he reported to Howe, upward of 3800 barrels of flour, soap, and candles, 25 barrels of horseshoes, several thousands of hatchets, kettles, and entrenching tools, and 20 hogsheads of resin, in a barn at Valley Forge; but it was not until the 20th that the Guards and Light Infantry were ordered forward with some Dragoons to destroy the magazine. As they approached at five a.m., they were fired upon by the sentinels and an officer of the Guards slightly wounded. They took the whole. This is Captain Montressor's story which differs from that of the Americans.

Quarters of Acting Brigadier Gen. Agnew, late home of Jos. Williams, Jr. (from photo taken in 1940) Colonel Dewees with some help had labored all the night before in the removal of the stores by wagons and rafts to a place of safety. Washington, who was then in the vicinity of the Trappe, had sent his youthful aide-de-camp, Colonel Alexander Hamilton, attended by Capt. Harry Lee and six dragoons, with orders to destroy that which could not be removed. In corroboration of this, Sarah Stephens, then in her nineteenth year, a few days before had left her home in lower Tredyffrin in company with her aunt, to visit the hospitals in Philadelphia in search of her aunt's son, Jheu (sic) Stephens, who had been wounded in the battle of Brandywine. On their return they rode up the east side of the river as far as Paulding's but found the fords impassable, and finally in the early morning obtained passage on one of the rafts constructed by Colonel Dewees and were ferried across to Valley Forge where they saw Leo guarding the stores while Hamilton was engaged in their removal. As the two women rode out the Gulph Road and drew near the old schoolhouse at the crossing of the Baptist Road, a troop of British Dragoons approached silently with a guide whom Sarah recognized but refused to name. Here the officer rode up to inquire if they came from Valley Forge and had seen Colonel Dewees removing stores. He received the Quaker affirmative and proceeded toward the river, but not by the direct route. The mill stood on the right bank of the Valley Creek not far from its mouth. Approaching either way there is a long down hill road which then led to a bridge over the mill race. Eastward on the summit, Lee had posted two videttes, both of whom fired and galloped down the hill as the enemy came into view. Colonel Hamilton had provided a flat-bottomed boat at the river's edge and instantly ordered the remaining four members of his little party aboard. Captain Lee, preceded by his two videttes, made quick decision to regain the bridge and escape up Nutt Road by the speed and soundness of his steed. Hamilton and his men struggled desperately against an adverse current increased by recent rains, while the enemy engaged by Lee's bold rush for the bridge, delayed for a few minutes their attack upon the boat, which enabled them to escape. Colonel Dewees' horse on a raft was the only casualty on the American side. Lee's apprehension for the safety of Hamilton increased as carbine volleys issued from the riverside. He trembled for the probable fate of his comrade and as the pursuit of his own party ended, he dispatched a dragoon with a note to the Commander-in-Chief, reporting the occurrence and expressing his presentiment of disaster. Washington had scarcely read the note when Hamilton appeared with the conviction that his friend Lee had been cut off, inasmuch as directly after the Captain had turned for the bridge, the British horsemen had reached the mill. Washington with joy relieved his fears by handing him Lee's dispatch. This was one of Lee's favorite stories after the war. Since the stories were almost all removed, there was nothing the British could do in their rage but apply the torch to the saw mill, dwellings, store, charcoal, and iron storage houses and the forge, to the ruin of the proprietor, as he had anticipated. Owing to Montressor's entry in his journal as of the 23rd when they fired Valley Forge, there has been some doubt among later historians of the exact date of the destruction of the forge. Woodman could not give the exact date but asserted that it occurred a short time previous to the massacre at Paoli. However, Colonel North, who was secretly observing the British camp from Mt. Joy, noted the conflagration on the 20th and later, with William Jackson and George A. Baker, signed as witness. Captains John Davis and Benjamin Bartholomew estimated the damages sometime after the war, and in 1809, seven years after Dewee's death, $7500 was allowed his widow.

Quarters of Maj. Gen. Grey, the Howell Tavern, demolished in 1935 Years ago some writers proved to their own satisfaction that the forge was much lower down, not in Tredyffrin, but on the opposite side of the creek in Upper Merion, also that it was not burned down. I well remember when an old resident pointed out to me the traditional site in Tredyffrin, as well as the cartroad down Mount Misery from whence the charcoal came, the private trail on the west side of the creek to Nutt Road over which the pig-iron was hauled from Warwick, and the road over the dam breast and its continuation in the rear of Mount Joy to Fatland Ford. Subsequent excavations have proved the traditional site and I can now offer proof that the forge was destroyed by fire in a piece of charred timber taken from the ruins. (To be continued) |