|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 3 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 1940 Volume 3 Number 3, Pages 52–57 The archeological expedition of the university museum to Panama, 1940

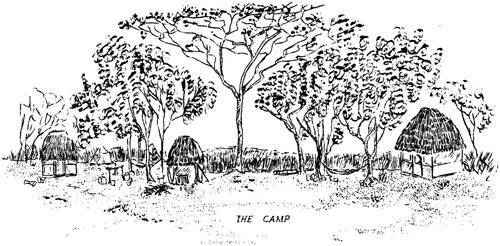

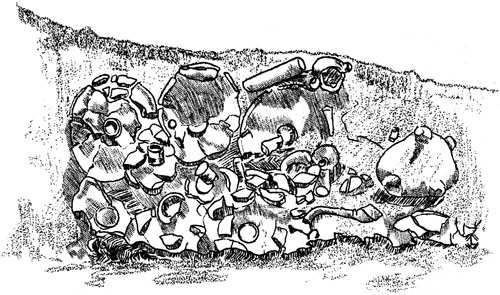

Owing to the present disturbed conditions in Europe and the Mediterranean, certain funds which are ordinarily spent for archeological work in Egypt and the Mesopotamian region became available late in 1939 for work in America. As the terms required that they be spent for the increase of the Museum collections, any project of pure research, such as a study of certain nearly extinct Indian languages of western Mexico, a job which I had long been eager to do, was out of the question. It was decided, therefore, to make excavations at a pre-Columbian Indian cemetery in the province of Cocle, Panama, where the Peabody Museum of Harvard University had dug for three years, in 1930, 1931, and 1933. They had secured many beautiful, artistic and unique specimens from an Indian culture that was heretofore quite unknown. Though there was no certainty that the site had not been exhausted, the probability was that much more remained there, and the results amply justified this hope. As work could be done there only during the short dry season which begins in January, the expedition was arranged very hastily, but I was very fortunate in my selection of personnel. As surveyor and engineer I was lucky enough again to get the help of Mr. Robert H. Merrill, a retired consulting civil engineer of Grand Rapids, Michigan, who had accompanied me in researches in Durango, Mexico, in 1936. Mr. Merrill now devotes most of his time to archeological work and is equipped for it, both by interests and training. He did a magnificent job of surveying, plotting, and photography, with such meticulous results that we could replace almost every specimen in its original position, depth and associations. If we return, we could again dig down to any point that we wish, although, in accord with the terms of our contract with the owner, our pit was filled up after work ceased in order to prevent injury to stock animals. Mr. and Mrs. John B. Corning of the University Museum and of Chestnut Hill served as assistant director and as camp-superintendent, respectively. Mr. Corning had had a thorough training in anatomy at Harvard and could at once identify any human bone and its owner's sex and approximate age. He also has great practical ability and before leaving made a study of the technique of preserving soft fragile water-soaked objects and of taking motion pictures. Mrs. Corning naturally took charge of the kitchen and the camp, in addition to assisting in the excavations, cataloguing and packing. My son, John, Jr., a senior in Tredyffrin-Easttown High School, also went along as general helper, and did most of the needed jobs around the camp as well as helping with the excavations. Though he lost the year in school it was a wonderful experience for him and the repetition of the school year is not regretted. Especially, however we were fortunate in securing the help of Dr. and Mrs. S. K. Lothrop of the Peabody Museum of Harvard University who were in charge of the last expedition of that Museum at this site. They helped us in making preliminary arrangements, accompanied us for several weeks and set us to work efficiently, after which they left for researches in another part of Panama. It is a pleasure to express my appreciation to all the other members of the Expedition for their efficient aid, hard work, and pleasant relations. By mail and cable we made contact with an agent in Panama who made the necessary arrangements with the owner of the property and with the Government of Panama. The latter at first insisted that the National Museum must receive a certain percentage of the finds, which was agreeable to us, but the landowner objected that the Government had no jurisdiction over his property - and proved his argument. However we intend to send a representative collection to the National Museum of Panama. The Lothrops, my son John and I sailed from New York on a "swanky" steamer of the Grace Line on January 12; the Cornings followed two weeks later, and Merrill traveled via New Orleans. The day after leaving chill, slushy New York we were in balmy weather which continued the rest of the trip. Our first stop was at Barranquilla, South America, from which it is only a step to Panama. The traverse of the Canal was most interesting and we left the steamer in Panama City on the Pacific side. The trip down on the palacial boat filled with tourists was the epitome of luxury, and in great contrast to the return trip. Although the latter was on one of the better boats of the same line, on account of the diminution in tourist traffic due to the war this boat had been turned into a freighter, limited to twelve passengers. Most of the cabins, the great dining salon, the bar, the swimming-pool, and most of the other luxuries were closed. Instead of evening dress at dinner we agreed that any man who appeared at meals with a necktie on would be at once thrown overboard. We left the camp on April 14, sailed from Panama April 17, and arrived in New York April 24. The expedition was a success in every way. The great explorer Stefansson says that for a scientific expedition to have adventures is a sign of lack of preparation or foresight, or of knowledge of the country; we had no adventures, no illness and no discomfort, and all members of the party were happy and congenial. In addition to the many beautiful objects secured, and to Mr. Merrill's admirable plans, careful scientific notes were made on all excavations, and about two hundred excellent photographs were taken as well as many hundred feet of motion picture film, both in color and in black and white, showing all phases of the life and work. On arrival at the site two large houses were built with board floors, thatch roofs, and walls of canvas and netting. One of them was used as the headquarters house for dining and work, the other was occupied by the Cornings. The other members of the Expedition lived in three tents. We also built a kitchen, small piers at the river for the laundress and for bathing, and bought two small native houses for the use of the camp help and for storage. We had an excellent cook who was able to provide delicious food prepared in all possible ways. Although Panama is blessed with nine months of rain, of course our work was done in the dry season, and we had only one thunder-shower and several light drizzles during the entire period. The region being on the Pacific side is of a nature very different from that of the Atlantic slope. Instead of the dense forest of great trees that we were accustomed to at Piedras Negras it is an open country with much grass and few trees, used entirely for grazing. During our stay it was very arid. The temperature was very high, certainly over one hundred degrees in the sun every day but the dryness of the air and the strength of the almost continuous trade-winds from the north-west made it very comfortable. There were only one or two evenings when we felt at all inconvenienced by the heat. The insects, one of the great discomforts of life in the tropics, were very few. On trips outside the camp we were certain to be covered with tiny ticks, but those in the camp-enclosure disappeared after a few days. Owing to the dryness of the season there were practically no mosquitoes. Venomous snakes are rather common in the region and we took great pains to keep the paths in the camp enclosure cleared, and always kept at hand the anti-venim and apparatus for treating snake-bites, but no member or employee of the expedition was bitten. For the Gorgas Memorial Laboratory in Panama City we collected snake-heads for their survey, paying the natives for such heads brought in. The report on those heads indicates that only twelve of the one hundred and eighty-three heads collected were those of poisonous snakes, and all but one of these were of the small Coral snake. However, the cook was frightened one day by having a very large boa fall on his floor from the roof. Frequently native wild animals were brought in to us and at various times we had around the camp anteaters, armadillos, squirrels, and parakeets. All of these died or escaped except for a little fawn which thrived, became very tame, and was taken to Panama City.

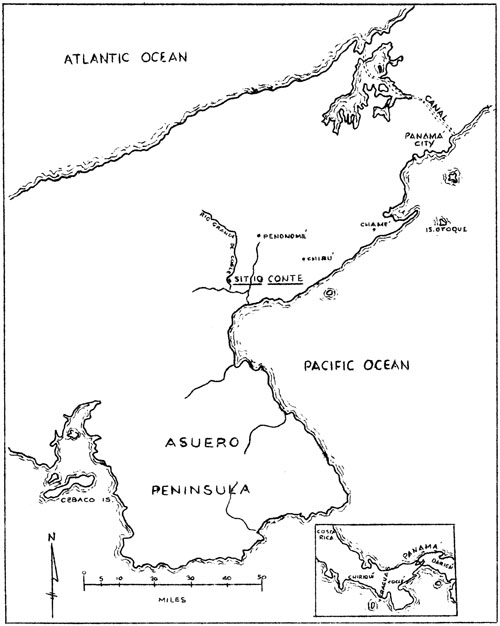

The Camp The present population of the country is not great, as it is a non-agricultural, cattle-grazing country. The natives live in scattered houses along the river where they grow corn and other crops for their own use, but are often forced to move during the deep floods of the rainy season. They are a mixture of Negro, White, and Indian, with the former predominating. It is a pleasure to record the friendly personality and perfect honesty of these natives. Both our expedition and that of the Peabody Museum left gold ornaments in plain view in the ground for several days at a time without any loss, and nothing whatsoever was stolen from the camp during the entire period. With their sharp eyes they constantly found gold beads and similar objects in the dirt thrown out, and I firmly believe that they turned over to us every piece of gold thus found. They are a happy though very poor people, and the relationship between them and the members of the Expedition was most cordial. The principal diversion of the people is a celebration or dance one of which is held at some house in the region at least once a week. The men and women dance by couples, but independently, to the music of a number of native drums and the singing of the rest of the women. At these "Tamboritos", as they are called, enormous quantities of a native beer made of corn and called "chicha" are consumed. Several of the members each brought home one of these native drums. It is a precedent for every expedition to give a "tamborito" with free "chicha" before departing, and our dance afforded an interesting side-light on Panamanian life. We had ordered about forty gallons of chicha for the crowd that we expected and had announced a certain night for the fiesta. It takes three or four days for the chicha to ferment, and it becomes sour and vinegary in a few days more. On the morning of the dance a policeman came from a nearby town to announce that by order of the Governor of the province all festivals, public or private, were called off for that night. It seemed that the "official" candidate for the presidency in the coming election was to be in the nearby town of Penonome early the following morning, and all the inhabitants of that region were expected to be there to give him a welcome. As we had gone to considerable expense to prepare for our farewell, I sent the Governor a telegram explaining conditions and asking for special permission to go ahead, with the promise that the dance would break up by three in the morning in order to permit the people to get to the "popular" demonstration. He replied that we might hold the dance on the condition that we broke up at midnight. As it turned out it would have been better to postpone it a day or two, as most of the population assumed that our dance had been prohibited like all others, did not learn of our permission and only about half the number came that we expected. Most of our food was imported, but chickens and eggs were available and occasionally natives came in with game such as venison, and some large birds. The greatest delicacy however, is the "tepesquintli". This is the Aztec name for an animal found throughout much of Central America; locally it is known as the "painted rabbit". Occasionally fish are caught in the river and a small sawfish was caught which had probably ascended from the ocean. Large crocodiles formerly inhabited the river, and there must have been many in aboriginal days, but most of these have recently been shot, though some are said still to be found in pools not far from the camp. Much of the last two weeks in camp was spent in packing. As wooden boxes were difficult to secure we made most of the boxes of lumber. Sixty-four boxes weighing some 6600 pounds were packed with pottery and stone, all but three of these being of small size. Most of the equipment was left at the ranch house of the Contes, in expectation of a return next year. The site of the work is a place which our contract stipulates is to be known as the Sitio Conte, or "Conte Site", from the name of the owner of the property. It lies in the province of Cocle, about a hundred miles west of Panama City, and possibly ten miles from the Pacific Ocean. There are no surface indications and the field looks exactly like those in hundreds of square miles of surrounding territory. The ancient inhabitants had no masonry but lived in houses of wood and thatch like those of the present natives. On some of the surrounding sites rudely sculptured small stone columns have been found and some have been unearthed at this site, but they were under ground and show no surface indications. The nearest large town is Penonome, fifteen miles to the northeast where the Conte family have their residence. In this flat country the rivers frequently cut new channels during the floods of the rainy season, and some forty years ago the Rio Grande de Cocle cut a new channel and disclosed this small area as an aboriginal graveyard, when pottery and gold ornaments began to be washed out of the river banks.

The closeness of the river was a great advantage as it permitted bathing after the hot work of the day, afforded water for drinking, and cooking after it had been boiled, and for washing objects. The site obtained considerable local publicity, and gold ornaments from here were frequently sold in Panama City. The owner made some small excavations many years ago, but it was some years before the site reached the attention of museums and archaeologists in this country. As a result of this the Peabody Museum of Harvard University conducted excavations there in 1930, 1931 and 1933. One large publication treating of non-pottery objects has been published by the Peabody Museum (Memoirs, Vol. VII., 1937), and Dr. Lothrop has finished a second volume on the pottery. (To be Continued) |