|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 3 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

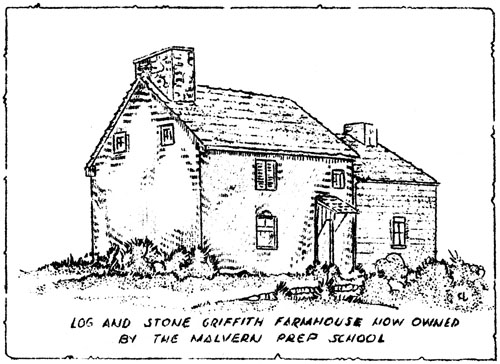

Source: July 1940 Volume 3 Number 3, Pages 58–72 II. The invasion of Tredyffrin: THE PAOLI MASSACRE Enroute to Warwick, Washington detached Wayne to threaten the enemy's right flank as soon as he broke camp in Tredyffrin and attempted to cross over the fords of the Schuylkill. Smallwood with his division of Maryland troops, variously estimated at from 1,850 to 2,600 men, coming up in the rear of the British army, was to reinforce Wayne as soon as it became prudent to attack, and he was to also act in conjunction with Maxwell's Light Infantry and Potter's Pennsylvania Militia ordered to the enemy's left flank, if it could be accomplished without too much loss of time. Wayne's Division moved from Yellow Springs in the early morning of the 17th of September to above Paoli and on the 18th selected a camp site on the Griffith farm, south of the present town of Malvern, on the plateau a short distance west of the continuation of the Longford road loading up from the Warren Tavern and about two miles above the Paoli Inn. As the Division had lost much of its baggage at Chadds Ford, the camp was largely of huts of fence-rails and brush. Here Wayne was in a position for a quick attack and he believed his presence was unknown to the enemy four miles away.

Log and stone Griffith farmhouse now owned by the Malvern Prep School Acting Division Commander, Brigadier General Wayne's Command, based upon the known fact that some of his regiments had been reduced to almost company strength, consisted of about 1,350 Pennsylvania Line troops, brigaded and regimented as follows:

FIRST BRIGADE:

SECOND BRIGADE: At least a part of the 3rd and 6th Regiments were also present, together with a company and four pieces of Field Artillery and two troops (Capts. Jones and Stoddard) of Bland's Dragoons, commanded by Lt. Col. Temple of Virginia, making a division of actual, not paper strength, of barely 1,500 men fit for duty. Col. Caleb North was posted on the summit of Mount Joy, Valley Forge, and Whitehead Weatherby, a patriotic citizen of Easttown, on the South Valley hills, to make observations of the British camp. In the early hours of the morning of the 19th, word was passed back that the foe was beating reveille and the Division marched by its left flank to White Horse, but as the enemy did not move, the troops returned to camp before dawn. Wayne, however, had secured reliable information of the enemy's intention to take up his line of march for the Schuylkill at two a.m. on the 21st, so he sent Col. Chambers on the 20th to conduct Smallwood's Division to the Paoli camp preparatory to an attack, while he, with Cols. Hartley and Temple, reconnoitered the road leading to the enemy's left flank, and as night approached and it was raining, ordered his men to lie upon their arms and protect their cartridges with their coats.

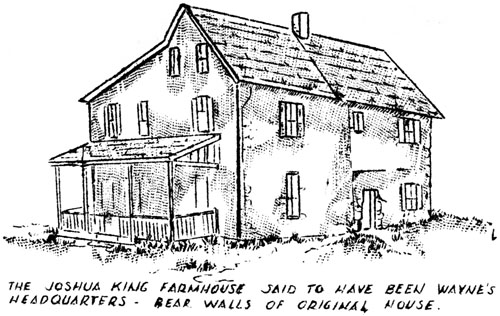

The Joshua King farmhouse said to have been Wayne's headquarters - Bear Walls of original house Eager to be off as soon as the Marylanders arrived, he next ordered his horse led out in front of his quarters at the King farmhouse, saddled and holstered, with his cloak thrown over the saddle to keep it dry. With a flooded river on the enemy's front, Wayne wrote Washington: "We only want you in their rear to complete Mr. Howe's business." The British Commander was not nearly as supine as Wayne thought. He refused to move until a dangerous foe was driven from his rear and had spies and scouts abroad who secured not only exact information of the identity and number of troops, the approximate position of their camp and the roads leading thereto, but even their countersign and of Wayne's intention to attack at an early hour of the morning; and Howe's intelligence appeared common knowledge in the Light Infantry camp. Between nine and ten o'clock of the evening of the 20th, a patriotic Welsh gentleman, Thomas Jones, a retired farmer of Easttown, came to Wayne with the information that a bound boy, a servant to William Clayton, landlord of the Black Bear Tavern, had wandered down the Bear Road in search of a cow and had been detained in the British camp for a short time, where he heard some Light Infantrymen speak of an attack to be made that night upon Wayne's camp. Cols. Hartley, Brodhead and Temple were present during the interview. Wayne instantly ordered out additional videttes to patrol all roads leading to the British camp and planted two new pickets, making six in all, exclusive of the horse picket under Captain Stoddard, well advanced on the Swedesford Road. Brigade Major Nichols, going the rounds, missed a sentinel, but a light horseman dispatched to the spot returned to report that the man was on duty and all was well. Wayne testily advised Nichols to go to bed. The enemy detachment was already assembled on the Swedesford Road in the vicinity of the Davis Schoolhouse and Howell's Tavern, commanded by Major General Grey, the same cold-blooded officer who later superintended the surprise and slaughter of Bayler's regiment near Old Tappan, New York, and who was finally rewarded with the title of Earl. His force consisted of the 2nd Battalion of Light Infantry composed of the best drilled and most active companies from six regiments, the 42nd and 44th Regiments, and some Light Dragoons. The 42nd or "Black Watch" was the famous Scotch Highland Regiment, and the whole command appeared well fitted for the desperate enterprise. Grey, sensible of the difficulty in distinguishing friend from foe on a night expedition, ordered the charges drawn or the flints removed from all muskets and the attack to be made with bayonets and swords only. From the 2nd Brigade there came the 40th and 55th Regiments under Lt. Col. Musgrave, as a reserve. They filed off over the fields to the left at eleven p.m., gained the (Old) Lancaster Road at the Bear tavern by the way of the Bear road, and took position across the road and fields at the Paoli Tavern. They were not engaged. A detail searched the Wayne homestead for the General and even thrust bayonets through a large boxwood bush at the corner of the house, hoping to find him, but otherwise behaved with politeness to Mrs. Wayne, though they carried off her two man servants.

Paoli Inn Grey's column advanced on the Swedesford Road at ten p.m., preceded by an advanced guard of four Dragoons, a company of Light Infantry, a company of Riflemen armed with swords, and one or two troops of Light Dragoons, whose duty was to dispatch all sentinels. At or near Bull's Corner, the advance was challenged two or three times and fired upon by one of Stoddard's videttes, who then put spurs to his horse and escaped. The column turned south on the Longford Road (Valley Store) where the first sentinel challenged, fired and escaped, and another likewise near Warren Tavern. Tradition states that the British made use of the American watchword but the sentinel discovered they were not Americans and fired. Every adult male inhabitant along the route was hustled out of bed and taken along to prevent an alarm being given. It is related that a corporal's guard entered the home of Captain Bartholomew on the Swedesford Road and took an aged uncle clad only in his night shirt. He died shortly afterward from the exposure and rough treatment received at their hands.

The Batholomew Homestead - remodeled Peter Mather, landlord of the Admiral Warren, was pulled from his bed and, unclad as he was, forced downstairs and out to a row of tall poplar trees in front of the tavern, where there was a crowd of civil prisoners coupled together like malefactors and under guard. Mather was bound to Squire Bartholomew, a man of almost eighty years. Mrs. Mather forced her way to her husband and helped him on with his buckskin breeches.

The Warren Tavern, original tavern was on opposite side of the road Here a party was sent to fetch the blacksmith, whom they forced to guide then to the picket a few hundred yards up the road. Two sentinels were dispatched by the riflemen's swords after they had challenged and fired. Lt. Samuel Brady of the 6th Regiment was on guard and lying down with his blanket buckled around him. Tho British advance was nearly on the picket before the sentinel fired. As Brady jumped a fence, an infantryman struck at him with his musket and pinned his blanket to a rail; the officer of the picket tore loose and ran. A dragoon overtook him and ordered him to halt. He wheeled and shot the horseman dead, then escaped to a small swamp in which he hid until morning. The expeditionary force, guided by the straggling fire of such of the retreating picket who had escaped their bayonets and swords, reached the summit of the hill and saw at their right the line of huts by the dim light of the dying campfires and the glimmer of a few stars. General Grey then rode to the head of the column and commanded, "Dash on, Light Infantry!" Without another word, the whole battalion dashed into the woods and gave such a cheer that made the wood echo. Many of the Americans were taken completely by surprise. Some with arms, others without, ran barefooted in all directions. The Light Infantry bayonetted every man they came up with, while the Dragoons raged, sabres in hand. The 44th Regiment followed to bayonet all who had escaped the first line, and the 42nd Regiment followed in close rank. Even some of the British officers were horror-stricken at the havoc. "The shrieks, groans, shouting, imprecations, deprecations, the clashing of swords and bayonets, no firing from us, little from them, except now and then scattered shots, was more expressive of horror than all the thunder of artillery," so wrote a British officer. The enemy gained the plateau about midnight, hence the slaughter was consummated in the early morning of the 21st. Howe stated in his report "about one o'clock." The attack was made in the most fiendish manner, the enemy shouting "No quarter to the Rebels!", and in derision the American watchword: "Here we are and there they go!" Many were awakened by the cry, "Up, men, the British are on you!", and could offer no defense while they endeavored to form, and in consequence were routed from the field. There were many narrow escapes. Chaplain David Jones barely escaped. Sergeant Andrew Wallace of the 4th, a native of Scotland, was hard pressed in camp and jumped into a clump of chestnut saplings, where he hid until the enemy had passed. His brother was killed, but he lived to relate his various campaigns with Wayne until 1835 at the reputed age of 105 years--one of the last survivors of Paoli. At the first alarm the 1st Regiment, supported by some Light Infantrymen and Dragoons, had been posted in a strip of woods some 300 yards in advance of the right. Wayne's order to Captain Wilson, senior officer in Col. Chamber's absence, was to "Stand like a brave soldier and give them fire". This frail line broke after one scattered and ineffectual volley, and the enemy rushed upon the 7th, which was next in line and at a great disadvantage in the light of their own campfires. The huts were immediately set on fire and with the cries of the wounded presented a dreadful scene. When the first line broke, Wayne endeavored to cover the retreat with the 4th Regiment, and, later, with the assistance of Lt. Col. North and Captain Herman Stout of the 10th, rallied enough men to form a rear guard to all who had taken the right direction to reach the summit of a hill on the White Horse Road. At the first alarm the Artillery, which was on the right, had been drawn off, but the repeated orders of General Wayne, carried by his aide, Major Ryan, to Col. Humpton, had been misunderstood and some troops had taken the wrong direction and out of support. Only a part of the enemy, perhaps a company or two, had followed the Artillery on the White Horse Road where they encountered the 4th Regiment. The main push was through the right of the camp and beyond, almost at right angle with the White Horse Road along which the American Left retreated. Grey followed the disorganized Americans who had fled out of all possible support, but soon satisfied with the damage inflicted, sounded the recall and returned to the camp in Tredyffrin with eight captured baggage wagons, many arms, and a reported loss of Captain Wolfe and three men killed and four men wounded. When the attack had driven through, the advance of General Small-wood was encountered and easily dispersed. Most of the Maryland troops (with one Delaware regiment) were raw recruits, the same who later made that brave and hopeless stand in the battle of Camden, determined to die with DeKalb, rather than flee with Gates and the militia. Of the Americans, the 1st lost Dr. Christian Reinick, surgeon mate, slain, besides some privates; the 2nd, 1st Lt. Walbron killed and 2nd Lt. John Irwin badly wounded; the 4th, Major Marion Lamar whose last words were, "Halt, boys, give these assassins one fire!" The 5th lost Ensign William Magee and two privates, and the 7th, Col. Grier, Captain Robert Willson, Lt. Andrew Irvine, wounded, the latter with seventeen bayonet stabs, and 61 men, exactly half of the men on the ground fit for duty. There were some privates wounded in the 8th, 11th, and Col. Hartley's Regiment. Exclusive of the two regiments in reserve at the Paoli Inn, the British probably numbered about 2,000 men, while at no time were there over 200 Americans in active opposition to them. The total American loss cannot be definitely known. It has been placed at from 150 to 300 men, with a probability that the former is more nearly correct. Stille gives the loss in slain as 61 men. There are eight Revolutionary soldiers buried along the wall south of the gate to the St. Peter's Cemetery whom tradition indicates as the picket slain near the Warren Tavern, and 53 mangled dead were found upon the field and interred in a double row in a trench 12 by 60 feet by the yeomen of the neighborhood, and another body found two weeks later in the woods was buried where it lay. The poor, mutilated bodies were wound in their blankets, with squares of linen cloth over their faces. The linen weaver, James Neilley of Old Cockletown (now Berwyn) claimed to have furnished the sheets from which his wife cut the squares for that purpose. While the citizens were engaged in gathering the dead and wounded, a number of British officers rode up to view the ground and they erroneously reported 460 Americans lying dead and their own loss as only 20 killed and wounded. Howe in a letter to Lord Germain stated that no less than 300 Americans were killed or wounded on the spot, showing that the British estimates of losses are not to be depended upon. The local people have always referred to this as the Paoli Massacre and how nearly correct they are may be told in the report of Howe and the journals of his officers. Of the 71 prisoners carried off, 40 were so badly wounded that they had to be left at different houses along the road. Two excavations for foundations to monuments, 1817 and 1877, in which the remains of seven or eight bodies were removed to one side, revealed an equal number of bayonets and proved that these men had been slain before the removal of their bayonets from the scabbards. In 1877 there were little left beyond a few of the larger bones (the thigh bones of one man appeared those of almost a giant), besides small pieces of cloth, cloth-covered pewter buttons, bayonets and a knife blade or two. We hear to this day canards of Wayne's supposed laxness on this, the only occasion in which he was taken by surprise. The most plausible may be easily disposed of, this substantially as follows: A Whig farmer sent his bound boy early in the evening with a message apprising Wayne of the contemplated surprise. Wayne was at home in Waynesboro playing cards with some of his officers when the boy delivered the note and, in his abstraction of the game, stuffed it in his waistcoat pocket and subsequently forgot it. Later, when he heard firing in the direction of the camp, he jumped on his horse and galloped forward to observe the enemy close upon the camp, and quickly turned his cloak with the red lining outward, boldly dashed up on the enemy front, halted the line as one in authority, and then rode back to rally enough men to cover his retreat! Gossip like this is venison and wine to the pseudo-historian. In fact, a recent biographer, without the least authority, intimates that practically the whole camp was in a state of intoxication! In view of the fact that Judge Futhey's excellent account has been accepted and quoted almost verbatim by Dr. Godcharles and others, it should be observed here that Prof. Teener's technical study has shed additional light upon the engagement and corrected some obvious errors. There were apparently two practical routes open from the north, both leading up from the Warren Tavern through ravines and that the enemy took the easternmost where there was an unaccountable slackness in guarding the approach. The assault was some distance east of the monument and burial ground, and the attack composed of English and Scottish troops only. Tradition places the actual campground on the plateau on which the present Borough of Malvern has been erected, along the lines of the former West Chester Intersection R.R., now King Street, and that the spring flowing into the Great Valley on the North was used by the troops. Judge Futhey is our authority for the statement that the King farmhouse was Wayne's Headquarters, though a local tradition thus honors the Griffith log house which probably was the quarters of Acting Brigadier Hartley. Grey's detachment was guided by a local Tory spy who was perfectly familiar with the situation and approaches to the American camp. He has been described as a man who limped badly, who had a wife and seven children eight miles away, and who later with his family departed from Philadelphia with the British army. General Wayne and some of his officers were informed of his identity but his name is not essential here. THE HIGHWATER MARK OF BRITISH INVASION In the early hours of Sunday, September 21, immediately after the return of the detachments from Paoli where Howe trumped Washington's ace with Grey, the British army in Tredyffrin broke camp and took up their line of march directly for the Schuylkill. An observation party had found the Swede's ford strongly guarded on the opposite bank with cannon behind breastworks. Here was General Armstrong with the Pennsylvania militia. Picked corps from the British army could and often did move with rapidity, but the ponderous army as a whole seldom averaged above five miles in a day. The forward movement began at five a.m. by way of the Baptist and Gulph Roads to Valley Forge and out Nutt Road. The evening's camp extended along that road from Fatland Ford to Fountain Inn (Nutt Road and Bridge Street, Phoenixville, the direct road to Gordon's Ford). The site is marked with a boulder as the farthest inland point reached by the British invasion of the Northern Colonies during the Revolution. The headquarters was at the first house below Bull's tavern, then occupied by William Grimes, and Knyphausen's quarters was midway between the Corner Store and Morris' woods, home of Frederick Buzzard. Montressor reported that all the houses along the route were filled with military stores, probably removed from Valley Forge, and immediately after the army encamped, hordes of soldiers swarmed out of camp in search of plunder. A detail raided the farm of Captain Patrick Anderson along the Pickering Creek and burned his furniture and butchered his cattle and sheep which they dressed in the best room of the house. It is said that Lord Cornwallis entered the home of Benjamin Boyer after it had been more or less dispoiled and where the owner had carried his bee hives and covered then with sheets. Cornwallis, not to be deceived, impatiently removed the covering. The rebel bees flew into his hair, stinging him unmercifully, and compelled his retreat from the room. Meanwhile, Washington had called in his detachments, crossed breast high at Parker's Ford on the 19th and took up position along the Reading Road from the Trappe to Evansburg. Tradition places his headquarters at the home of D. Morgan Casselberry, from where he rode out to Fatland Ford to observe the movements of his opponent. Howe's move up the river was interpreted as a threat to gain his right, prevent the juncture of Wayne's and Smallwood's divisions with the Continental Army, and to destroy the military magazines at Reading; so, on the 22nd, Washington moved westward on the Reading Road to Limerick and thence on the road leading by Swamp Tohr, and encamped in the vicinity of Falconer's Swamp southeast of Fagleysville on the Sanatoga valley or Crooked Hill slopes. Headquarters was at the home of Col. Frederick Antes, and the militia, stores, and bake ovens were nearby. Wayne and Smallwood, in their retreat from the White Horse, turned northwest at Limerick, and the former camped on the farm of Andrew Smith, where the wounded from Paoli were operated upon on a bar-room table. Camp Pottsgrove established strong outposts at Swampdoor east of Fagleysville, Jackson Hill near Sanatoga, and Washington Hill near Potts' Grove (now Pottstown), and here the ragged and rugged little array had a brief repose among the "Pennsylvania Dutch" until the 26th when it again moved back to the Perkiomen Creek at Pennypacker's mill. British couriers reported that Washington had retreated to Reading, so on the 22nd at five p.m. the Hessian Grenadiers passed over Gordon's Ford, under cover of artillery and small arms fire, and returned again to deceive chance observers, and at the same time the British Light Infantry and Grenadiers passed over Fatland Ford and took position on the eastern side. On the 23rd just after midnight, the whole army moved over and by ten a.m. the last had passed over with the heavy baggage without opposition. At Gordon's Ford the Dragoons were in advance, followed by the Hessians who began to chant their German hymns as the water reached their knees. Cornwallis accompanied this column and Howe at Fatland Ford. American scouts shot and killed two British officers at the upper ford, but there appeared no serious opposition. Howe with the right wing united with Cornwallis at Bean's Tavern via Ridge and Swedesford Roads, and on the 26th entered Philadelphia, the goal of forty days on the high seas and thirty-two more days on land, having marched, as one of their generals recorded, a hundred miles cheerfully and successfully, subsisting on the country and with nothing to drink for many days but water. If they had not dependable guides as volunteers, British gold or the prick of the bayonet secured all necessary information.

The farthest inland point reached in the British invasion of the northern colonies during the Revolutionary War September 21-23, 1777; erected by the borough of Phoenixville... DAMAGE INFLICTED UPON THE INHABITANTS OF TREDYFFRIN AND EASTTOWN BY THE BRITISH ARMY Major General Grant wrote that they continued their march on the 18th to Tredyffrin where they were obliged to halt two days, as the wagons could crawl no further. It is well known that the British lost hundreds of horses while at sea, but it is not generally known that when on the march from the head of the Elk, they were virtually without tents, baggage, provisions, or a possibility of communication with the fleet, but it is so stated by Grant. A state of affairs which would have proven disastrous had the Americans been more nearly equal in numbers, training, and arms. The damage sustained by the peaceful inhabitants of our neighborhood through the emissaries of "His Most Graceous Majesty King George the Third" that "fusty old drone from the German hive," in less than three days occupation, is almost beyond belief, since they wanted everything except arms and ammunition. One farmer bitterly characterized Howe as a falsifier of his word and a plunderer of private property. Another wrote, "Not even a spoon left to eat my victuals nor a comb to comb my head." There is a long list of damages for the loss of stock, grain, forage, provisions, wagons, harness, saddles, tools, household furniture, metal and earthenware, linen, blankets, personal apparel, objects in gold and silver, but not a single firearm, and only one silver-hilted small sword, that of Surgeon Davis. One negro slave valued at 130 pounds was stolen from Samuel Havard. Samuel Jones (Howe's headquarters) lost all of his crops and livestock except one horse which they were unable to catch. Abel Rees (Cornwallis' quarters) lost everything including the two ends of his barn and his apple orchard, and Christian Workizer (Agnew's Quarters) likewise, including thirty apple and peach trees destroyed. Howell's Tavern and farm losses, itemized, included 1 hogshead of whiskey, 1 ditto run, 20 gallons gin, 3 horses, 23 head of cattle, 36 sheep, 500 bushels of wheat, large quantity of other grain, and 6,000 fence rails. Samuel Davis lost the entire stock of his store consisting of a hogshead of rum, two wagonloads of earthenware, crock of butter, cake of tallow, snuff, tobacco, coats, trousers, trimmings, sewing silk and remnants, gold weights and scales, money out of drawer, and his account book cut and destroyed to the amount of 300 pounds. Doubtless his farmer customers ran accounts payable after harvest. Beside other losses, Dr. John Davis lost what was then considered a very full stock of medicines consisting of:

The Havards lost heavily, especially in household goods, personal apparel, and luxuries, in which they appeared more liberally supplied than many of their neighbors. Their losses included the following interesting items:

The Rev. Dr. William Currie, on the Yellow Springs Road opposite the camp, circumstantially related that "On the 19th of Sept., 1777, a Company of Soldiers from Camp Came to my House and Robbed me of all my Cabbage Bacon Cheese & Butter, a Bushel of fine Salt, & all my fine Sheets, Table Linen fine Shirts head Dresses, Stockings, & Table Silver Spoons to the value of 20 pounds. There is the Strongest Presumption--Likewise that at the Same time they robbed me of 200 pounds Continental Money in Sheets the money 3 for 1 is 66.13.4 and the day following a forraging party took from me two Wagon Loads of Oats one do. of wheat, besides Several Horse Loads of Both, a Good Cart & Geers all my Wagon and Plow Geers, Collars & Blind halters & Ropes, 2 Mens Saddles, half worn & 3 Bridles all of which I Judge to be worth 20 pounds." A detail went to the Leopard to rob the Rev. Dr. and Brigade Chaplain David Jones of his riding chair, 14 sheep, 1 hog, 17 geese, 105 bushels of wheat, etc. Valentine Shewalter, Jacob Baugh, and Thomas Pennington did not itemize their losses, but an approximate total of some commodities commonly itemized by the local inhabitants is given below.

Philip Upright (Epright), as well as many others failed to respond to the call of the State in 1782 for a list of damages. Epright had been a redemptioner from Saxony, after which he prospered from 1771 to 1777 as a tenant landlord of the Blue Ball Tavern, until the night of the massacre above Paoli, when the British under Colonel Musgrave plundered him of his all. Ruined, he filed no claim, but quietly gave up his lease. Since none of the Quaker families and few of the Mennonites made returns, and others neglected to do so, it is difficult to estimate the total loss in Tredyffrin and Easttown. Possibly the appended list represents fifty per cent of the neighborhood cost of entertainment and that the total damage reached $50,000, a large sum for those days. If there remains any question whether our community remained undecided, pro-Whig or pro-Tory, we might take into consideration the contrast in the treatment of the inhabitants by the haughty invader and by the paternal American Commander. Howe left a path of desolation, while Washington was always considerate of the right of the farmer. The list of damages in Tredyffrin:

Easttown

Credit from the British Paymaster

Source Material Andre, Captain John; Journal, Vol. I. Boyd, Thomas; Light-horse Harry Lee. Burns, Franklin L.; Ms. Collection of Local Traditions. Chester County Historical Society; Ms. Transcription of Damages in Tredyffrin and Easttown by British Army. Putney, J, Smith; One Hundredth Anniversary of the Paoli Massacre. Putney, J. Smith, and Cope, Gilbert; The History of Chester County, Pennsylvania. Harris and Smith Collateral Ancestry. Grant, Major General James; Major Cuyler's Excerpts from Letter. Am. Autograph Journal, December 1939. Linn, John B.; Annals of Buffalo Valley, Pennsylvania. Linn, John B. And Egle, William; Pennsylvania Archives, Vol. X, Second Series. Pennypacker, Charles Whitaker; Annals of Phoenixville and Its Vicinity. Pleasants, Henry; The History of Old St. David's Church (de luxe edition). Stille, Charles J.; Major General Anthony Wayne and the Pennsylvania Line. Streets, Priscilla Walker; Lewis Walker and His Descendants. Woodman, Henry; the History of Valley Forge. Acknowledgements are also due to Henry J. McQuiston, Paul Prichard, Howard S. Okie, Mildred F. Bradley and Mary W. Baugh for the loan of photographs and to R. Brognard Okie for the fine sketch of Agnew's quarters. The drawings were made by Caroline Logan. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||