|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 18 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: January 1980 Volume 18 Number 1, Pages 15–20 When Wharton Esherick Had His Studio in Paoli It somehow seems fitting that it was a cherry tree in full bloom that induced Wharton Esherick to make his home and studio near Paoli in 1913. A young painter at that time, he was later to become known and recognized for his woodcuts, his wood sculpture, and his unique hand-crafted furniture, utensils, and accessories. In the spring of 1913 Esherick was looking for a place in the country, within twenty-five miles of Philadelphia, and preferably on the water. Someone suggested the Paoli area to him, and in late May he was shown a farm house and barn on about five acres of ground on the south side of Diamond Rock Hill. Near the house was a large cherry tree, about four feet in diameter, in full bloom, its feet in the well. When Esherick saw the tree, the search was over; he hardly even looked at the house itself because, as he explained to the realtor, he would probably change it anyway. Wharton Esherick was born in Philadelphia, in the area of 36th and Locust streets, on July 15, 1887. He was one of seven children, including a twin sister of whom he was very fond. From the time he could hold a pencil, his mother used to say, he was never without pencil and paper, drawing continuously, filling every piece of paper in the house with drawings and sketches. He attended the Philadelphia public schools, was graduated from Central Manual Training High School, and then studied for two years, despite his parents' objections, at the Philadelphia School of Industrial Art, from 1907 to 1909. The only artist in the family, his work was not really taken seriously by the family until he won a scholarship to the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. At the Academy he studied painting under William Herritt Chase and Cecelia Beaux. Finding the academic atmosphere too restricting, however, he left shortly before completing his course of studies to draw commercially, first for two Philadelphia newspapers and then for the Victor Talking Machine Company. When improvements in the reproduction of photographs eliminated his job at Victor, he decided to move out of the city and devote full time to his painting.

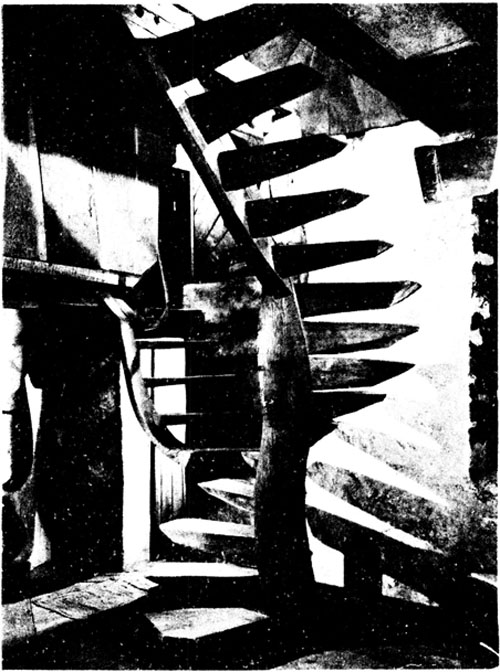

Wharton Esherick He used one of the bedrooms of his new Paoli home for a studio, producing landscapes and a self-portrait in a neo-impressionist style. He also tried raising turkeys, until he discovered how stupid turkeys are and the problems of turkey farming. He did cultivate the orchard and raise his own vegetables, however, with a few chickens from time to time. When his first daughter, Mary, was born in 1916, the bedroom was needed for the family, and he moved his studio down the hill to the old Diamond Rock octagonal school house, which he also helped fix up and renovate. Among other contributions to its restoration, he made the shutters, forging the iron work himself, so similar to antique iron work that on several occasions part of it was stolen. During the First World War, Esherick became involved in camouflage work. Although he wanted to be in the service, since he had a small farm he was encouraged to do his part by raising wheat. According to his daughter Ruth, however, he was definitely a better artist than farmer. Following the war, from friends at Arden, Delaware, he heard about another single-tax colony similar to Arden, located at Fairhope, Alabama. An artists' colony that attracted writers, painters, and other artists, it also conducted an experimental school for organic learning. In 1919 Esherick joined the faculty to teach drawing. (It was here, incidentally, that he first met and became friends with Sherwood Anderson.) It was also at Fairhope that Esherick first became interested in working in wood after meeting the widow of a German woodcarver, who offered him her late husband's chisels and tools. Returning to Paoli in 1920, but no longer needing his barn for a horse, he converted the barn into his studio, putting in large windows over the old hay mow for skylights and adding a fireplace. The Diamond Rock School studio was no longer large enough for both his painting and his woodworking interests, with the press he needed to print his woodcuts. His first wood carvings were frames he especially designed and carved to complement his paintings, but he also experimented with woodcuts and with some small figures and pieces of furniture. His first sculpture was actually a game, a horse race with six brightly colored horses and two dice, now titled The Race, while among his early woodcuts were prints of his farm on Diamond Rock Hill and a winter scene of the restored Diamond Rock School. After a few years, he decided that woodcuts and sculpture were really his primary means of expression. His first commissions were for book illustrations, including woodcuts for special editions of The Song of Solomon, and The Song of the Broad Axe. It was also at about this time that he first became interested in the theater, designing sets and producing posters and other graphic material for Jasper Deeter's newly-formed Hedgerow Company. During performances, for his personal pleasure he would also make numerous sketches of the action on the stage. He even was an actor in one of the plays, but it was evident that acting was not really his forte. By 1926 he again needed more room for his studio, as well as a chance to get away from Mary, Ruth, and Peter, his three children, while he worked. Having acquired additional land on the hillside north of the farm, he designed a separate studio, modeled after a barn, which his friend Louis Kahn has described as "a splendid example of architecture by inclination". On the top of the hill, just off the Horseshoe Trail, it was built of natural field stone and old barn timbers, to blend into the hillside and become a part of its surroundings. Esherick built the studio with the help of four men. On the date stone are the initials "WE" and "AK", in recognition of the assistance given by Albert Kulp, while in the entrance way the workmen are represented, together with an ever-present songbird, by four hand-carved coat pegs along the wall, cariacatures of John Schmidt, a carpenter, carved from mahogany; of Bert Kulp; of Aaron Coleman, a black hod-carrier, carved from ebony; and a beer-bellied Larry Hand, while above them is a sixth peg, depicting Wharton Esherick, hammer in hand. (Most of Esherick1s early carvings were made from imported woods, rosewood, snakewood, ebony, mahogany: it was later that he favored the native woods and more natural forms.) The dominant feature of the studio is a spiral oak staircase, with massive, irregularly shaped steps fitting into the large trunk of an old tree. It was added in 1930 to replace the original staircase connecting the two floors. (After its installation, it was dismantled on two occasions for exhibition, including at the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair, and then returned to its original setting.)

The spiral oak staircase in Wharton Esherick's studio, also exhibited at the World's Fair in New York in 1939-1940 Everything in the studio was hand crafted. The door latches were individually hand carved, with the door hinges also forged by Esherick. Similarly, the furniture, utensils, and accessories were all hand crafted, with additions made during the forty years he spent building, enlarging, and altering the studio. Each piece took its form from its natural characteristics. As Louis Kahn observed, "Esherick would take a piece of wood or stone and, in using it, he would never allow it but to be itself. Even when it was finished as a stool or a table or a wall, it maintained a sense of its basic identity." Even the iron grilles for the heating system ducts were cast from designs Esherick traced with his finger in a sand mould, a map of the farm, showing the road leading into it, the farm house and barn and pathways, the orchards and gardens, the woodlands and fields. Esherick's first one-man show of his sculpture was at the Wayne Gallery in New York in 1927, and in 1933 there was a show of his sculpture and drawings in the Mellon Gallery and of his prints and woodcuts at the Philadelphia Print Club. Pieces of his sculpture were also included in exhibitions at the Whitney Museum in New York and at the Brooklyn Museum in the late 1920's and early 1930's, as well as in the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, and the Philadelphia Art Alliance. Socially, Esherick tended to keep to himself, perhaps even more so than other artists, though he included among his friends people like Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, Ford Madox Ford, and Louis Kahn. He disliked crowds and random conversations. He also traveled little; as a teen-ager he had been to England and Ireland, while in 1931 he traveled in Bavaria and Scandinavia and in the 1950's visited in Mexico. He also returned for a visit to Fairhope in 1930, where he experimented with carvings in the native Alabama sandstone, and with ceramics. But most of his work was done in wood. During the 1930's he became best known for his furniture and interior designs, for which he received many commissions, perhaps the best known of which was for an entrance hall for the home of Judge and Mrs. Curtis Bok in Gulph Mills. With the architect George Howe he also designed and created a model interior for a Pennsylvania Hill House for the 1939-1940 New York World1s Fair. The exhibit included the spiral staircase from the studio in Paoli and a couch from the Bok home, among other furnishings that were designed for their efficiency and function as well as for their unique artistic qualities. Some of these furnishings, notably a large white pine and mahogany sofa, incidentally, were later incorporated into the studio, and when a wing was added to the studio in 1941 the rough-hewn cherry panels that had been a part of the model house at the Fair were used to panel the side walls. It was through George Howe that Wharton Esherick first met the architect Louis Kahn, on whose views of design he was to have great influence and who was to become a close friend. In 1956 the two collaborated to built a new workshop, a few yards to the northwest of the studio, made of cinder block but again designed to harmonize with its surroundings. With this additional working space, the main floor of the older building was turned into a sitting room and study, and a gallery for his work. (After Esherick's death, the building was made into a museum to exhibit over 200 pieces of his work, including paintings, woodcuts, prints, sculpture, furniture, and utensils that he had created over a sixty year period of activity. It is also on the National Register of Historic Places.) In the meantime, both his sculpture and his furniture became widely known and were exhibited in many galleries and museums. His work was included in exhibitions not only throughout the United States, but abroad as well, including a traveling exhibit in 1952 entitled Sculpture of the 20th Century; three U.S.I.A. Fine Arts traveling exhibits; and at world's fairs in Brussels and Milan. The Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, the Whitney Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Crafts, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and the Library of Congress also have acquired representative pieces of his work for their permanent collections. Wharton Esherick was still active when he died on May 6, 1970, at the age of eighty-two. His work, ever the years, revealed a "progression from natural forms, through the sharp prismatic angles of cubism, eventually evolving into swirling, lyrical forms wanting to be touched as well as viewed". (One of his sculptures, Andante was in fact named by a blind musician during Esherick1s second visit to Fairhope.) K. Porter Aichele, in the catalog of the Esherick Museum collection, has noted that "he developed a style uniquely that was his own", a style "evolved, at least in part, out of his commitment to merging fine craftsmanship with creative design". It was Louis Kahn who recalled, "Trees were the very life of Wharton... He had a love affair with them, a sense of oneness with the very wood itself... I could never be around him for a very long time without feeling some deeper and more profound appreciation and respect for nature." And this is why it somehow seems fitting that it was a cherry tree, its blossoms full, that brought Wharton Esherick to Paoli. TopSources

Interview with Ruth Esherick Bascom |