|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 18 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 1980 Volume 18 Number 3, Pages 89–95 Dating Old Barns Architectural history may be observed in the many styles of residential, commercial, and industrial buildings that remain a part of our landscape. Over time, there have occurred both stylistic and functional changes in agricultural buildings as well. These adaptations illustrate the evolution of American farming. As Bernice Ball points out in her Barns of Chester County, "The functional quality of barns makes them more neatly tied to their time and place than any other type of building." A barn's architecture is as indigenous to its region as to the era of its construction. The reason for this is that each group of settlers who arrived in the new world brought with them the vernacular architecture peculiar to their European homelands. In the early stages of colonial settlement, barns were distinctly recognizable as English, German, Swiss, and so on. As America emerged out of scattered settlements, farmers borrowed from one another those structural and functional adaptations for their barns that were best suited to the climate and the available building materials of their surroundings. The English style barn is typically a three bay structure with a single deck. In plan, it consists of two mows separated by an aisle, with wagon doors at each end. Early barns of this type were of frame construction; later versions were built of stone, brick, and combinations of stone and frame. In Pennsylvania, the English barn often appears as a two-level barn, with the characteristic three bays. TopSome Tredyffrin Barns

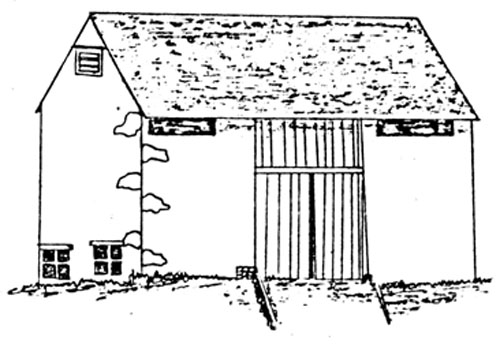

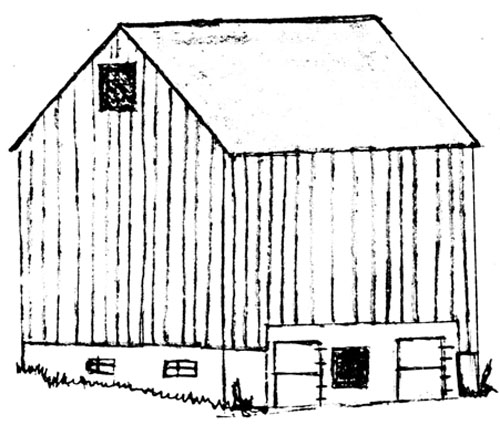

Barn at Poole's Headquarters Repportedly Built in 1732

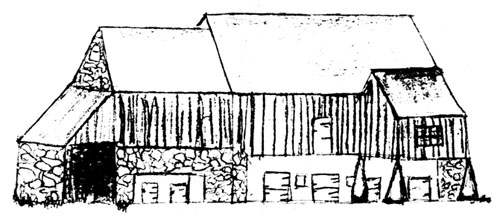

Barn at Pulaski's Headquarters Dated 1739

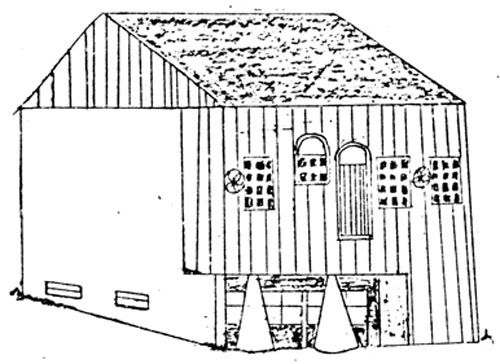

"Federal" Barn at DuPortail Complex Dated 1791

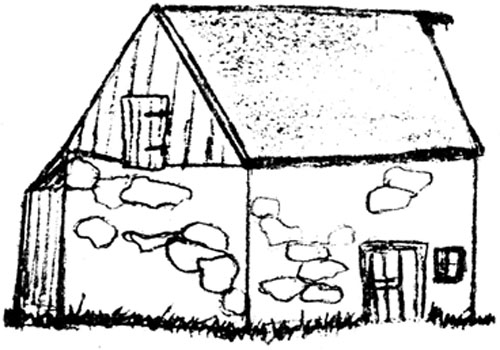

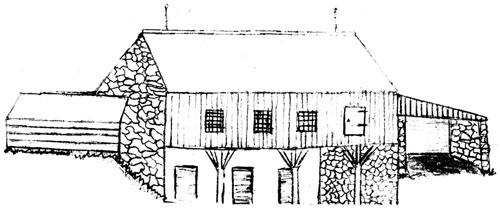

Barn on Clare Property Yellow Springs Road Reportedly Built from Stone from an Old Blacksmith Shop

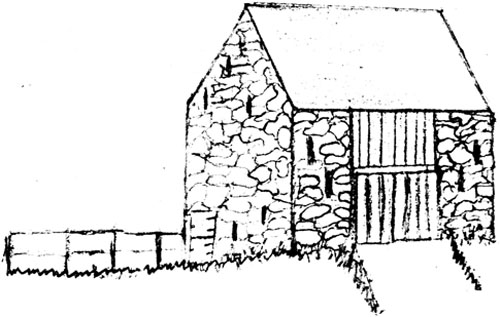

"Thomas Walker" Barn at Stirling's Headquarters 1750 - 1820

Barn on Scott Property North Valley Road Dated 1800

"Tory Hollow" Barn Early 19th Century

"Acker" Barn - 1850 with Tenant House Attached

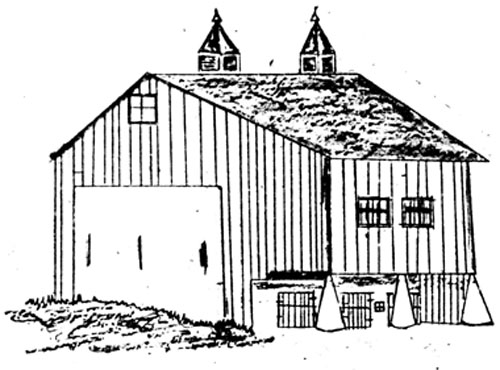

Barn at Knox Hqtrs. Built About 1860 on Older Foundation

Barn on Wildman Property Yellow Springs Road 1860-1890

Barn on Claypoole Property Yellow Springs Road

"Potts" or "Fairfields" Barn - Late 1800's Yellow Springs Road On the earliest frame barns, the siding shows the vertical scars of the "up-and-down" saw. After the first quarter of the nineteenth century, the gang saw was often used to cut siding; it leaves a horizontal scar. While pegs were used to hang siding as late as the 1890's, after 1790 hand cut nails were also used. Machine-made nails also appear after the Civil War. The Pennsylvania barn traces its design origins to Swiss and German ancestry. The Bavarians frequently built log and stone barns, banked at a right angle to the lee of a hill. Often, the farmer's house was attached to the bam. In the New World, these traditions were adapted. For instance, although Pennsylvania barns are commonly banked, the long axis is parallel to the crest of the hill. The house and barn, as a rule, are separate structures. The early German barns were single deck, with a stable floor below. Often they were built of stone and logs. A distinctive feature of this style is the laube, a shallow projection of the upper wall on the south side protecting the byre or stable openings. This shallow projection is the forerunner of the great cantilevered mows that typify the Pennsylvania or Quaker barn. The German barn was widely used after 1750. Until about 1750, the great wooden doors to the barn floor were simply braced shut by poles, and removed for ventillation during the summer. It was not until later that wagon doors were affixed with hinges. Sliding tracks were used after the turn of the century, and roller doors appear after 18^0. By the end of the eighteenth century there were more than 9000 log barns in Pennsylvania, a figure that suggests that over half of the barns in existence at the time of the Revolutionary War were log barns. Few of them are still standing. Of the early barns that do remain, most are built of stone. Often vertical openings, segmental arches, and large quoin stones appear in the stonework. Occasionally, one will find a date stone or a signature in stone or plaster that will provide clues to the history of the building. (The "Federal" barn at DuPortail's headquarters is an example of a "signed" barn.) Later, barns were constructed with stone gable walls and foundations, the rest being made of frame and timber. In barns built between 1700 and 1800 the structural timbers were roughly hewn, as was the five-sided ridge beam. (The absence of a ridge bean usually dates a building as of this era.) Architectural fashion may well have dictated the disappearance of the log barn by about 1800. By then, improved construction techniques made possible larger frame barns, required by the increased prosperity of 19th century fanning. The "Quaker" barn in Chester County is as typical of this area as the "salt box" house is of New England. The barn traces its name to the fact that it was most often found within ten miles of a Quaker meeting house. These banked stone and frame structures are double decked and usually feature an expansive cantilevered forebay and a banked or bridged entrance to the upper floor. Inside, twin hay mows are divided by a threshing aisle which runs the width of the barn, ending in a straw shed. The straw shed consisted of the cantilevered projection; by 1860 it was included under the main roof and supported by conical columns. The 19th century barn is also likely to have a flattened ridge beam, while its 18th century predecessor had a rough-hewn, five-sided timber, as noted earlier. As late as the First World War, the framing was joined by mortise and tenon, with wooden pegs the most common method of securing the timbers. The heat produced by stored hay is known to attract lightning. Thus, for a frame barn full of hay, lightning was a serious threat. Duringthe 1800's, farmers recognized the importance of adequate ventillation to reduce the heat inside the barn and thereby the risk of being hit by lightning. Cupolas on the roof, dormered louvered vents, and windows were introduced at this time to provide this ventillation. During the Victorian era, cupolas tended to be ornamental as well as functional, consistent with the architectural fashion of the day. Stylistic changes in barns are subtle. This is because there is a lag between vernacular and design architecture. Barns were generally altered and enlarged with a greater regard for function than for style. Barns are also highly susceptible to fire; in many instances new barns were raised on old foundations. The granary is often the most finished section of a barn. Where lathing is exposed, it will sometimes give a clue to the barn's age. Accordioned oak sheets were used between 1700 and 1820, while sawed lathing is common after 1850. Farm technology and productivity increased dramatically during the late 1800's. Dairy farming became predominant in Chester County. Many old barns were therefore outfitted with milking stanchions, and new barns built after the 1890's were designed especially for dairy use. Some more modern ones included cement floors, plumbing and electricity, although these fixtures were not in general use until about 1910 and later. Barn design has changed slowly from 1700 to 1900. The characteristic colonial barn was small, built of stone, with a shallow, cantilevered forebay. The barn typical of the 19th century was of frame, double decked, and much larger than its colonial counterpart. The "Quaker" barn is characterized by an enlarged overhanging forebay, supported by conical columns. Much of the barn building of the 20th century has consisted of rehabilitating existing barns, with some experimentation with new designs that depart radically from their historical forebears. |