|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 21 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: April 1983 Volume 21 Number 2, Pages 43–50 General Pasquale de Paoli The village of Paoli took its name from the old Paoli Inn, opened in 1769 near the intersection of the then Darby-Yellow Springs Road and the road to Lancaster, (It was about where the post office is now.) The Paoli Inn, in turn, was named for the Corsican patriot Pasquale Paoli. By the mid-eighteenth century, in his fight for Corsican independence, General Paoli had become a symbol for liberty. He was born in 1725. When he was only ten years old, he followed his father, who was also a Corsican patriot, into exile at Naples. Returning to Corsica at the age of 30, he was named commander-in-chief of the Corsicans in their continued struggle for liberty and against Genoese rule. After a series of brilliant actions, he succeeded in driving back the Genoese and confining their occupation of the island to just a few towns along the sea coast. Two years later, in 1757, as head of the Corsican government, he instituted a number of reforms, including a recognition of the sovereignty of the people and their participation in the affairs of the nation. General Paoli's fame was perhaps at its height at the time the Paoli Inn was opened and named. The previous year, some twenty-three years before his famed biography of Dr. Samuel Johnson, James Boswell had had published his An Account of Corsica, The Journal of a Tour to that Island; and Memoirs of Pascal Paoli. In it he enthusiastically supported the cause of the Corsicans, and of the General he observed, "I saw my highest idea [of man] realized in Paoli".

Bryn Mawr College Rare Rook Collection The book, published in London by Edward and Charles Dilly, was apparently well received by the public, three editions of it being published, both in England and in Ireland. It was also translated into several other languages. (Dr. Johnson said of it, "Your history is like other histories, but your Journal is in a very high degree curious and delightful.") Boswell visited Corsica, an island about which little was known at that time, in 1765, making his continental tour "something more than just the common course of what is called the tour of Europe". With a letter of introduction from Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he not only met General Paoli in his palace at Corte, but for the remainder of his stay in Corsica "had every day some hours of private conversation with him". It was the beginning of what was to be a lifelong friendship between the two men. Using the same methods he later employed in his biography of Dr. Johnson, in his "memoirs" of his visit with the General, Boswell has provided us with an extensive sketch of the hero for whom Paoli was indirectly named. Pasquale Paoli, at the age of 40 when Boswell met him, was "tall, strong, and well made; of a fair complexion, a sensible, free and open countenance, and a manly, and noble carriage". His bearing, initially, was "polite, but very reserved". "I had stood in the presence of many a prince," Boswell reported, "but I never had such a trial as in the presence of Paoli. ... I was much relieved when his reserve wore off, and he began to speak more. "Before long, the Corsican became "more affable" - and even "amiable". But while he often had "a placid smile upon his countenance, he hardly ever laughed". At the same time, Paoli was quite spirited and "animated with an extraordinary degree of vivacity". It was reported that he never sat down, except at meals, and was "perpetually in motion, walking briskly backwards and forwards". He also had a prodigious memory. "I was assured," Boswell reported, "that he knows the name of almost all the people in the island, their characters, and their connections." Despite the fact that he had not the patience to "study above ten minutes at a time", he also had a broad knowledge of history, literature, and philosophy, and a "versatility of mind" that Boswell described as "amazing". "His memory as a man of learning," Boswell noted, "is no less uncommon. He has the best part of the classics by heart, and he has a happy talent in applying them with propriety." Reporting on the dinner conversation on the day Boswell first met Paoli, he wrote, "The General talked a great deal on history and on literature. I soon perceived that he was a fine classical scholar, that his mind was enriched with a variety of knowledge, and that his conversation at meals was instructive and entertaining." Later he noted, "He was well acquainted with the history of Britain. He had read many of the parliamentary debates, and had even seen a number of North Briton. He shewed a considerable knowledge of this country, and even introduced anecdotes and drew comparisons and allusions from Britain,"

Pasquale de Paoli

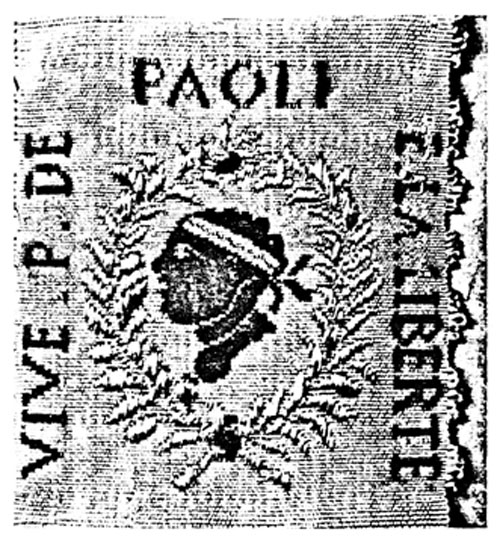

woven badge worn by followers of Paoll The General could also read and speak French, Italian, and English. At his first meeting with Boswell he conversed in French, but at dinner he spoke Italian, in which he was "very eloquent". He spoke English only "tolerably well", however, and very slowly since it had been ten years since he had last spoken it. His English library included Pope's Essay on Man, Swift's Gulliver's Travels, and Barclay's Apology for the Quakers, as well as broken volumes of the Tatler and Spectator. Boswell also reported that the General's mind was "fitted for philosophical speculations as well as for affairs of state". On one occasion at dinner, Boswell wrote, "he gave us the principal arguments for the being and attributes of God" with a "graceful energy" that was "admirable". "I never felt my mind more elevated," Boswell observed. On another occasion at supper the General "entertained us for some time with some curious reveries and conjectures as to the nature of the intelligence of beasts" and "in particular seemed fond of inquiring into the language of brute creatures", "He observed, "Boswell continued, "that beasts fully communicate their ideas to each other, and that some of them, such as dogs, can form several articulate sounds,. In different ages there have been people who pretended to understand the language of birds and beats. 'Perhaps, said Paoli, in a thousand years we may know this as well as we know things which appeared much more difficult to be known.!"

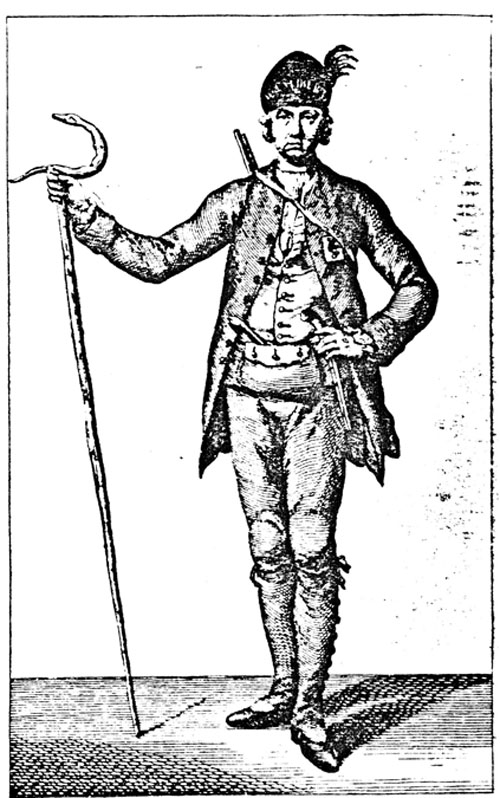

James Boswell, Esq. in a Corsican army uniform

as painted by Sir Joshua Reynolds Paoli was also a physiognomist. "In consequence of his being in continual danger from treachery and assassination," Boswell explained," he has formed a habit of studiously observing every new face." On their first meeting, he reported, "For ten minutes we walked backwards and forwards through the room, hardly saying a word, while he looked at me, with a stedfast [sic], keen and penetrating eye, as if he searched my very soul." While he dressed somewhat elegantly, for his meals "he chose to have a few plain substantial dishes, avoiding every kind of luxury, and drinking no foreign wine". His formal dress, in place of the common Corsican habit, was adopted upon the arrival of the French to make the Corsican government "appear in a more respectable light". Even his horse had "rich furniture of crimson velvet, with broad goldlace". For protection, in addition to soldiers continually on guard, Paoli had five or six watchdogs, which he treated "with great kindness" and which were "strongly attached to him". At night some of them slept in his chambers, others at the outside of the chamber door. The General also allegedly had a gift of clairvoyance, to see things in dreams that afterwards came to pass. He was quoted as confirming that "in general, these visions have proved true", but that he could give "no clear explanation of it". In any event, that it was so was "universally believed" in Corsica, Finally, General Paoli was described as a man whose notions of morality were "high and refined", and as one who had "very seldom deviated from the path of virtue". In addition to this description of Paoli's characteristics, Boswell has given another dimension to his description of the Corsican patriot by reporting some of his thoughts and ideas as "remarkable sayings", (At the end of each day Boswell recorded the events of the day, including excerpts of the conversation. In transcribing these conversations, he pointed out in the preface to his book, he "neither added nor diminished", but recorded them "without even the smallest variation" so that they would be "perfectly authentick".) Here are some of Pasquale de Paoli's observations. Of the importance of ancient history "A young man who would form his mind to glory, must not read modern memoirs, but Plutarch and Titus Livius." On happiness "He said the greatest happiness was not in glory, but in goodness; and that Perm in his American colony, where he had established a people in quiet and contentment, was happier than Alexander the Great after destroying multitudes at the conquest of Thebes," On sentiment and reasoning "If a man would preserve the generous glow of patriotism, he must not reason too much, ,,, I act from sentiment, not from reasonings," On words and deeds "If all the professors in Europe were formed into one society, it would no doubt be a society very respectable, and we should there be entertained with the best moral lessons. Yet I believe I should find more real virtue in a society of good peasants in some little village in the heart of your island. It might be said of these two societies, as was said of Demosthenes and Themistocles, 'The one was powerful in words, but the other indeeds," On social grace "I was known to be a singular man, I talked and joked and was merry; but I never sat down to play; I went and came as I pleased. The mirth I like is easy and unaffected. I cannot endure long the sayers of good things [bons mots]," On the arts and sciences "Corsica has fought a hard battle, has been much wounded, ...The arts and sciences are like dress and ornament. You cannot expect them from us for some time. But come back twenty or thirty years hence, and we'll show you arts and sciences, and concerts and assemblies, and fair ladies, and we'll make you fall in love among us, Sir." On marriage "If ... [a commanderj is married ... there is a risk that he may be distracted by private affairs,, and swayed too much by a concern for his family. If he is unmarried, there is a risk that not having the tender attachments of a wife and children, he may sacrifice all to his own ambition. ... I never will marry. I have not the conjugal virtues. Nothing would tempt me to marry, but a woman who should bring me an enormous dowry with which I might assist my country." (At the same time, Boswell reported Paoli "spoke much in praise of marriage, as an institution which the experience of ages had found to be the best calculated for the happiness of individuals, and for the good of society".) On the Corsican's hopes and bravery "I tell you on the word of an honest man, it is impossible for me not to be persuaded that God interposes to give freedom to Corsica. A people oppressed like the Corsicans, are certainly worthy of divine assistance. When we were in the most desperate circumstances, I never lost courage, trusting as I did in Providence." "Sir, if faith be, if the event [the war] prove happy, we shall be called great defenders of liberty. If the event shall prove unhappy, we shall be called unfortunate rebels." (He took great exception to the use of the term rebels to describe his army.) "If I sbould lead into the field an army of Corsicans against an army double their numbers, let me speak a few words to the Corsicans, to remind them of the honour of their country and of their brave forefathers, I do not say that they would conquer, but I am sure that not a man of them would give way. The Corsicans have a steady resolution that would amaze you. ... It is a saying among the Genoese, 'The Corsicans deserve the gallows, and they fear not to meet it.' There is a real compliment to us in this saying." "We may have foreign powers for our friends, but they must be 'Friends at arm's length'. We may make an alliance, but we will not submit ourselves to the domination of the greatest nation in Europe. This people who have done so much for liberty, would rather be hewn in pieces man by man, rather than allow Corsica to be sunk back into the territories of another country. ... The less assistance we have from allies, the greater our glory." On the role of the people in government "Our state is young, and still requires the leading strings. I am desirous that the Corsicans should be taught to walk of themselves. Therefore when they come to me to ask whom they shall chose [sic] for their Padre del Commune, or other Magistrates, I tell them, You know better than I do, the able and honest men among your neighbours. Consider the consequence of your choice, not only to yourselves in particular, but to the island in general. In this manner I accustom them to feel their own importance as members of the state." Boswell returned to London in February 1766. There he continued to promote the Corsican cause - to the extent that Dr. Johnson, in a letter from Oxford dated March 23, 1768, suggested, "I wish you would empty your head of Corsica, which I think has filled it rather too long," (Boswell replied, "My noble-minded friend, do you not feel for an oppressed nation bravely struggling to be free?") In the meantime, in May 1768 the Genoese sold Corsica to France. Although the French brought in more troops, Paoli had some initial success against them. But the Corsican resistance gradually broke down, and in May 1769 Paoli was forced to take refuge in London. With the help of Boswell, he was most popularly received in the British capital, and soon became acquainted with a number of notables, amomg them Dr. Johnson, Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, Edmund Burke, and Oliver Goldsmith. Dr. Johnson, after meeting Paoli for the first time, was most impressed by his ideas on language, and remarked to Boswell that General Paoli "had the loftiest port" of any man he had ever seen. After the French Revolution, Paoli went to Paris, where he was acclaimed as "the hero and martyr of liberty" and given the title of governor of Corsica, with the rank of lieutenant-general, by Mirabeau. Soon afterwards civil war broke out, with Paoli, aided by the British, opposed by a Republican group backed by the French army. When the Republicans were defeated, an assembly at Corte formally asked that the island be made a British protectorate. The British government accepted the offer, but named Sir Gilbert Elliott, not Pasquale Paoli, the viceroy. Paoli was recalled to England in 1795, where he again received a cordial reception. He lived there for the remaining years of his life, and died in London in 1807. He is buried in Westminster Abbey. |