|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 22 |

||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||

|

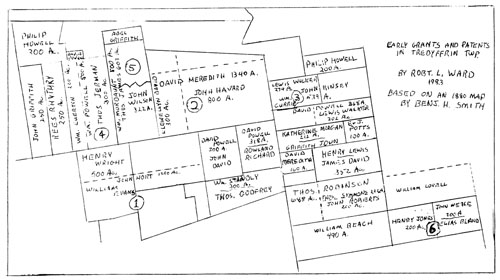

Source: January 1984 Volume 22 Number 1, Pages 17–24 Some Early Landholders in Tredyffrin The maps in Breou's Farm Atlas, published in 1883, were the first to show property lines in the various townships and boroughs of Chester County. Three years earlier a man named Benjamin Smith, who lived in Radnor, had published an atlas showing the original patents and land transactions up to 1760 in early Chester County, including all of what is now Delaware County. Some of them for Delaware County, particularly along Ridley Creek in the Tinicum area, where most of the early settlers were Swedish, are particularly interesting, with the titles actually traced back to Francis Lovelace, who was the governor of New York under the Duke of York. Unlike the other colonies, Pennsylvania was, in fact, a big feudal manor. The privileges which were normally granted to the lords of the manor were also granted to William Penn. Thus the land that Penn sold - and all the land that the Penn family sold up to the Revolution - was actually a feudal fief. Even after its purchase, a certain amount of money per acre had to be paid on demand once a year. For this part of the county this quit-rent, as it was called, was one penny for each 100 acres. While it was not a great deal of money, for a number of people it was a burden, and eventually led to a real rift between the early Welsh settlers and the Proprietor's Commissioners. To purchase land, an individual went before a Board of Property, which Penn had appointed to manage his property, with an application for a piece of land. If approved, he would receive a grant or deed from Penn for the amount of land purchased. A warrant would then be issued to the Surveyor-General, directing him to make a survey of the amount of land bought wherever the buyer chose, within reason. The Surveyor-General, in turn, would then send an order to a deputy surveyor to make the actual survey. There was one deputy surveyor for each county. Upon completion of the survey, the deputy surveyor made a return, after which a patent would be issued from the Board of Commissioners to the purchaser. Before William Penn left England he entered into an agreement with a group of Welshmen on July 11, 1681 to sell them a tract of 40,000 acres, to be laid out or surveyed when everyone got here. It was to be a tract where the Welsh could live and govern themselves according to the Welsh tradition, and use the Welsh language. Eventually it included Lower Merion, Haverford, Radnor, Tredyffrin, most of Easttown, part of Willistown, East and West Whiteland, and East and West Goshen - an enormous tract of land. Since most of the Welsh wanted to live as close to Philadelphia as they could, a settler buying 500 acres, for example, would actually get two tracts; one of 250 acres, say, in Merion or Haverford, and another 250 acres in the "back country" in Goshen or the Whitelands. While this western land was theirs, they simply did not do anything with it. Nor was the number of Welsh settlers as great as originally anticipated. The Commissioners, in the meantime, were anxious to get the land already surveyed as completely settled as they could before selling the land beyond that they had already laid out. When they realized that much of the western portion of the Welsh Tract was still vacant, they sent a letter to some of the leading Welshmen, asking them to justify the sale of this land only to the Welsh, and also demanding that the quit-rents be paid on the entire tract. Since the Welsh had said that they would pay the quit-rent only on the lands actually settled, the deputy surveyor for Chester County was ordered to survey land in the Welsh Tract for other purchasers. In his atlas tracing land titles up to 1760, Benjamin Smith actually included only a few townships of present-day Chester County. Among them were Tredyffrin, Easttown, and East Whiteland. Also included was Upper Merion Township in present-day Montgomery County. In his map of Tredyffrin Township Smith made some errors, though it was not altogether his fault as some of the records he used were not completely accurate. And in some of his research he just skimmed the surface. One example is in a 1,000 acre tract, in the southwest corner of Tredyffrin, which he shows as patented to John Hort (shown as #1 on the map on the next page). It stretches from the township line on the west to present-day Berwyn. But apparently there never was a patent issued for this property! Further, John Hort did not actually settle on the property, or send someone to manage it, or sell it for him within a prescribed period. Since the patent - if it ever existed - was never recorded, after that time the land was taken back and sold to someone else. The man it was re-sold to was named Henry Wright, with his wife Elizabeth, They also never left England, but eventually their grandson came to Maryland. Living in Cecil County, he sold 500 acres of the tract to Philip Yarnall, who in turn sold it to William Evans. The Evans family lived in Paoli for three or four generations. Joshua Evans, the son of William Evans, actually created the village when he opened the Paoli Inn, around which the village, with its shops and houses, grew up. The eastern section of this 1,000 acre tract was sold to another group of Welshmen; Owen Roberts, Hugh Roberts and Thomas Rees all took land there. This is not even shown on the Smith map, as by the time Smith had included the Hort information there simply wasn't enough room on the map for it! The deputy surveyor of the Welsh Tract was a man named David Powell, who also bought land for himself. When he first came to Pennsylvania he bought a farm in Blockley, now a part of West Philadelphia. He married Mary Havard, a widow whose late husband had purchased a tract of land in Cheltenham. They lived on it for a while, and then sold it and bought land in Radnor. Powell also bought property in Tredyffrin from John Meredith, who had originally obtained it from a patent from William Penn. It was a tract of 1500 acres (#2 on the map) which he divided into three farms. John Havard, Mary Havard's son and Powell's step-son, bought 800 acres in the center of today's Chesterbrook. A second tract of 300 acres, to the west, was sold to Lewis Walker who, in turn, sold it to Llewellyn Davis, whose son, Isaac Davis, was Justice of the Peace in Tredyffrin for over thirty years. Farther to the west, Powell sold a 300 acre tract to Rowland Richards. Another tract of 160 acres, to the east, was also sold to Lewis Walker. He was a neighbor of Powell in Radnor: in fact, they exchanged properties. Lewis Walker is said to have been the first settler to live in Tredyffrin. His home was called Rehobeth, just off Swedesford Road, (Walker was, in fact, responsible for originally building that part of the road. He also gave the land for the Valley Friends Meeting House, not far from his home.) Eventually he put together a tract of 600 to 700 acres (#3). It became quite a family compound, and part of the tract remained in the Walker family for nine generations. There are still descendants of the Walkers living in the area today: Conrad Wilson is one of them.

In addition to Rehobeth, there were two other Walker homes on the property. One is today called Many Springs Farm, on Walker Road; it was the farm of his son Joseph. Joseph's wife was a second cousin of Anthony Wayne, which is probably why Wayne chose this house for his quarters during the encampment at Valley Forge. Another son, Daniel, built and lived in a house off today's Thomas Road; it was used by General James Potter as his quarters during the winter of 1777-78. (Rehobeth itself, then lived in by Isaac Walker, was the quarters of General Nathanael Greene.) A 200-acre tract on the northern part of this property, which Daniel received from his father, was sold to the Rev. William Currie who lived there for a number of years before he bought land further to the east, just before the Revolution, from members of the Jones family. The Rev. Currie was an Episcopalian parson, at one time pastor at St. Peter's in the Great Valley, St. David's at Radnor, and St. James of the Perkiomen, across the Schuylkill River from Phoenixville. And before moving to Tredyffrin, he lived in Plymouth! As he was of middle age and getting on in years, he sensibly decided to consolidate his efforts by moving near to the center of his three churches. When he was in his 60's he was still making the trip to all three of his congregations! Another of Lewis Walker's sons, Enoch, married the daughter of local miller Thomas Jarman. Jarman had bought 300 acres (#4) from William Powell (who, I believe, was David Powell's brother and lived in West Philadelphia). The tract extended from just below Swedesford Road all the way back to Yellow Springs Road, a long and rather narrow tract of land. The story is told that Jarman and Lewis Walker entered into an agreement whereby Jarman's elder daughter Elizabeth was to marry Walker's son Enoch. At about that time Elizabeth fell in love with an indentured servant named James Anderson, a young Scotsman working at the mill to repay the passage money for his passage to America. To avoid separation they eloped, going over the hill to Charlestown where they lived among the Indians for a while. Their son Patrick was the first white child born in Charlestown; at the age of 57 he served with distinction in the Revolution. The Andersons were also the founders of the early Methodist Church in this area, and their home was an early Methodist center. (Before the Revolution the Methodists were still nominally members of the Church of England, but immediately after the war they broke away to form their own religious body.) As a result of the elopement, Jarman's other daughter, Mary, married Enoch Walker. (I guess it didn't matter so much in those days who married whom!) But Jarman apparently did not get along too well with his son-in-law, for in his will he put an entail on the property, providing that the land would be left to his daughter Mary "and the heirs of her body forever". This procedure is no longer legal in Pennsylvania. In order for their son Jarman Walker to dispose of the property, this entail had to be broken. To do this, a legal maneuver was used in which the elder Walker "sold" the land to a courthouse employee named William Marlowe where upon the younger Walker sued his parents for its possession. When Marlowe failed to show up when the case was called, the suit was won by default, and the entail broken. This maneuver was used countless times in such cases until finally the state legislature outlawed the whole procedure, as the only people profiting from it were the lawyers. Since Jarman Walker was not a miller by trade, he sold off some of the land and rented half of the mill to a man named John Rowland. The Rowlands had a mill on Valley Creek which they had purchased from the Davis family, but John Rowland now moved into the larger and better-known Jarman's Mill built in 1710. This was actually one of the earliest mills built after William Penn gave up his exclusive right to own and operate mills, a concession he had originally reserved to himself but which, because the demand upon him was so great, he later gave up, (Jarman's Mill - or, rather, its successor -is still standing on North Valley Road. I believe there are plans by its owner to put it back into operation again.) Immediately to the east of the Jarman Mill property is a tract of 500 acres (#5) that was originally warranted to William Mordaunt, who was from Llanstonwall in Pembroke, Wales. He never left England, and his two sons sold the tract to a man named John Evans. John Evans was the Governor at this time, having been appointed by Hannah Penn who acted as guardian for her husband William Penn during the last years of his life. Evans was a very close friend of William Penn Junior, and he and Billy Penn used to go out and "paint the town red". The constables couldn't do anything about it - who would want to arrest the Governor and the son of the Proprietor of the Province? - so they just escorted them home. But from what I've read, nearly everyone was glad to see them both return to England! John Evans married the daughter of John Moore, a judge who was the collector of customs in Philadelphia, a very important man who came from an aristocratic background, (John Moore's son, during the 18th century, became very prominent in Pennsylvania politics in the Proprietary Party, which was for the retention of the rights of proprietorship by the Penn family. The party against it, mainly composed of Quakers and German pacifists, was led by Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Galloway.) After Evans went back to England, Judge Moore sold the land for his son-in-law to a man named Thomas James. By that time it had been resurveyed and found to contain 607 acres. When Thomas James died, his widow passed it on to Lewis James, who was probably a relative and who also lived half in England and half in America. He eventually sold the property in two pieces; the northern half to the Rev. Francis Alison and the southern half to the Rev. John Kinkade. Kinkade lost his property after defaulting on the mortgage, and the 322-acre southern part was then sold to John Wilson. (See "The First Wilson Homestead" in the October 1983 Quarterly, Vol. XXI, No. 4.) The northern part, consisting of 190 acres, was bought by the Rev. Dr. Francis Alison, who established the Nottingham Academy -to which three signers of the Declaration of Independence went - before becoming the vice-provost of the College of Philadelphia. He used it as a summer home for several years, a practice not uncommon among Philadelphians. One of the advantages of the property was that, with it, Dr. Alison also received "first purchase" rights to two house lots in Philadelphia which he sold a few years later, together with one acre of land in Tredyffrin, to the same John Wilson. (This information I found in the Deed Books in City Hall in Philadelphia. Altogether, I found the deeds for sixteen properties in Tredyffrin recorded there, most of them for property which John Evans and the Jameses once owned, but some for a property in Berwyn owned by Thomas Godfrey.) The "panhandle" at the southeast of Tredyffrin also has some interesting stories to it. I have found several deeds for the area that refer to it as the "Barbados" tract. The tract (#6), which included 500 acres located in Tredyffrin, Radnor, and Upper Merion townships, was purchased by two Barbadian traders or merchants, Henry Jones and John Weale. Whether they lived in Barbados and managed the property from there, or whether they were from Barbados and then settled in Philadelphia, I do not know. I believe that Jones did die in Philadelphia, but I haven't been able to track down Weale at all. On the property is a house which the Valley Forge Historical Society received in 1970, known as the Armstrong House. When I was asked to search its title, I found some very interesting people were associated with it. During the Revolution it was owned by an Englishman named Elias Bland. He was a Quaker merchant in London, whose main business was as a contact with the great Philadelphia Quaker merchants; the Morrises, the Whartons and others. He was a very wealthy man, and had land holdings throughout the American colonies. His wife Hannah was the daughter of John Stamper, who was the Lord Mayor of Philadelphia in the 1760's. Bland received this Tredyffrin land from his mother, Priscilla Bentnall Bland, who was a descendant of John Weale. On his death, while returning to England in 1782, the land passed on to Elias' brother John, a London banker. After John died in 1787, his widow Margaret and their daughter began selling off the property in parcels, sometime after 1798. The entries for the property in the 1798 glass tax records indicate it was owned by a man named Phineas Bond, who was the Bland family attorney in Philadelphia. He was an interesting man in his own right, as he was a loyalist who fled to England during the war. When he came back he was never particularly accepted, even though his father was a socially prominent Philadelphia physician. While it has been suggested that the Armstrong House may be pre-Revolutionary, I don't believe it is. None of the houses found on the glass tax list for that property is stone; all of them are log houses. Further, the course of Upper Gulph Road was diverted so the house could be built, and I think that was done at a later date. One of the difficulties in tracing the early "genealogy" of property titles in Tredyffrin is the duplication of names in the area. For example, there were three different Davis families, none of them related; two different Jones families; and two different Evans families living in different parts of the township. When they first came to the area - and for the first two or three generations - . the first names used were pretty much within a family, but by about the middle of the 18th century they began to borrow and use the same given names, and it becomes extremely confusing. The failure to record some deeds also raises problems, I've already noted that some deeds were recorded in Philadelphia rather than in Chester or West Chester. In addition, in the Chester County Historical Society, in two archives boxes labeled "Tredyffrin Lands" and which contain miscellaneous deeds, mortgages, and research notes, are six deeds for property in Tredyffrin that apparently were never recorded any place. In fact, I would guess that up to half of all the deeds made in Pennsylvania during the 18th century were not recorded, despite the fact that by law they were not legal until they were recorded. As an example, in 1774 a man named Alexander Thompson, a Philadelphia schoolmaster, appeared before the Evanses in Paoli and reported he had received a deed to their property from the Player family of Bristol, England, who were heirs of John Hort. Finding to his astonishment that there were people already living there, he then went to the Board of Property in Philadelphia with his claim, and the Board, noting that the property had been occupied for more than 60 years, gave him instead a piece of property on the other side of the Susquehanna! This is an area that can stir your imagination, as you walk or drive down North Valley Road or along Swedesford Road through the Valley, and think about these old homes and the people who owned them and lived in them. I hope someday to publish a book about them, similar to Mrs. Kady Cummin's history of Radnor. (The author wishes to thank Elizabeth and Bob Goshorn for their help in transcribing and editing the tape of his talk.) |

||||||