|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 23 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: January 1985 Volume 23 Number 1, Pages 3–8 The Lenape of Southeastern Pennsylvania : A Brief History Of all the native people who occupied Pennsylvania at the time of European contact, only the venerable Lenape survive as an identifiable culture. Today descendants of the Pennsylvania Lenape living in Oklahoma still retain vestiges of their ancient ways. Most of the descendants of the Lenape, however, have merged with other native people, such as the Susquehannock, and with people of Swedish, Dutch, English, and African descent as well as with other immigrant groups. The interest in the Lenape who were here before 1600, and the ways in which they met the challenges of the European immigration, has led scholars at West Chester University, at the University Museum, the William Penn Memorial Museum, and at other institutions to use early documents, archaeological excavation, and oral history, as well as more traditional, anthropological techniques, to understand the peoples who once lived here. What has been discovered is of profound interest to us all. TopLENAPE LIFESTYLE IN 1600 A.D. The Lenape (meaning "The People") usually lived in bands of 25 to 30 members, each including several related family groups. Each of these extended family groups lived simply, generally eating and camping together. Each band occupied the valleys of one or two of the major streams feeding the Delaware River, which they called "Makeriskhickon". Perhaps as many as twenty different Lenape bands functioned at any one time, and their total population may have been as high as 1000 people. When a Lenape male married, he went to live in the band in which his wife was a member, and the children became members of their mother's band. (This is known as matrilineal descent.) He provided for his wife's family, but he also owed respect to his own siblings and to his own mother, and provided for them as well. The women gathered vegetable materials as well as growing some maize and beans in summer garden plots. Lenape women also collected small animals, such as frogs and turtles, and gathered shellfish. The Lenape men usually hunted in groups, in the surrounding forests, for deer, elk, bear, and birds, using the bow with arrows tipped with broad, flat, triangular stone heads, carefully chipped and sharpened. Lenape men also fished, using harpoons as well as traps and large nets made by their wives. Butchering was done with a "teshoa", a stone knife fashioned from a flake taken from river cobbles. Among the neighboring Munsee, to help insure a bountiful hunt, the men carried charms, and possibly small "maskettes" representing Meshingalikun, "Living Stone Face", the "Master of Game" who provided animals for man's food. The Lenape had similar customs, and a variety of different charms or amulets which were important in influencing Manetto, the "Great -Spirit". No storage pits are known in the the historical or archaeological records, so we infer that they ate all that they foraged. The Lenape thus maintained a delicate balance with their environment. In the past few years archaeologists have discovered many Lenape sites within the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Although excavations have been extremely productive, we have yet to discover evidence for a single house of the ancient Lenape. What we do know of their residences comes from William Penn, who provided one of the most direct descriptions of Lenape constructions: "Their houses are Mats, or Bark of Trees set on Poles, in the fashion of an English Barn, but out of the power of the winds, for they are hardly higher than a Man; ..." (in Myers 1970:27) The Lenape must have traded widely from earliest times. Their trade extended to the north to the Munsee, into Long Island and New England, and along the Hudson River, to the west into the Susquehanna Valley, and to the south with the Manticoke and people of the Powhattan Confederacy. To the Five Nations they were known as the "grandfathers", an honorary title indicating great respect. Lenape dead were tightly flexed and wrapped in bark. They were then placed in individual graves in carefully attended cemeteries, some distance from their summer settlements. Quite possibly some individuals were buried in the great forest, but these customs are just becoming known, Lenape mortuary ritual, like much of their culture, continues intact right into the twentieth century. Most of the Pennsylvania Lenape had left the Delaware Valley by 1740. Some bands of Munsee and Jersey Indians moved into Pennsylvania, after 1700, and by 1740 the term "Delaware" was extended by the colonists to all of these people. As the main groups of these people (Lenape, Munsee, etc.) moved west they often became more or less co-resident, and the naive European observers called them all by the term "Delaware". For the most part, the Lenape moving west maintained a clear sense of identity which has not been lost to this day. Much remains unknown about the ancestral Lenape. Wide areas are still to be surveyed for archaeological sites, and some sites may have been covered by the rising Atlantic along the New Jersey and Delaware coasts during the last four hundred years. Many Lenape sites have been wantonly destroyed by collectors of artifacts who have no regard for these important sites as documents of the past and evidence of our cultural history. But the prehistory and history of the Lenape are, nevertheless, becoming better known through a huge cooperative effort that is being made by all Lenape people and interested scholars. TopEARLY CONTACT PERIOD: 17th & 18th CENTURIES The first contacts between the Lenape and European fishing parties must have taken place well before 1600 A.D. Spanish missions were established on the Chesapeake to the south of the Lenape area in the late sixteenth century, and several Spanish and Portuguese explorers and traders must have visited the lands of the Lenape. It therefore seems reasonable to suggest that prior to 1609, when Henry Hudson traded with the natives of Sandy Hook Bay, the Lenape were acquainted with Europeans. By 1650 imported goods had displaced many native crafts, such as pottery making and flint knapping (or chipping). During the 16th century there was also European contact with peoples far to the north of the Lenape area, along the St. Lawrence and throughout New York, This too had a considerable indirect effect on the Lenape. Changes in Material Culture Although the Lenape never grew rich from the fur trade, and in fact suffered greatly from the predations of the Minquas intrusions before 1650, a number of improvements were made in their lives through European contacts. The introduction of metal was perhaps one of the greatest advantages that came from Europe. In addition, other gifts, bartered for furs and food, not only eased the lives of the Lenapes, but enriched their lives with pleasing colors and important symbols. But although the technological ability of the Lenape changed drastically, the culture (lifestyle, values, rituals) were all but unaffected by these substitutions in the material aspect of life. Iron tools, with their sharpness and efficiency, were perhaps the most significant material objects to reach the Lenape.. Although not sharper than the stone tools, iron did not break as readily and could be sharpened with ease. Copper, often coming in the form of kettles, could be cut up to make arrow points. Metals in general were valued for functional purposes, but not for decoration. Cloth was also a highly valued commodity. The Lenape found it warmer and softer and easier to work than skins. When trimmed with fur, it was far superior to the hide which took much work and care. Like metal tools, however, cloth goods were used in specific and functional ways and did not alter the cultural system of the people. Guns became a third category of European goods of value to the Lenape. They were used as defensive weapons at first, but later for hunting and warfare also. As well as with other items, it seemed to the naive that these materials created vast changes in Lenape life. In fact, traditional Lenape culture was hardly touched by these new commodities. The continuity of the past, the wisdom of the elders, and the ways of Lenape culture remained the same. Their language, their respect for the ways of the past, their daily lives, rituals, burials, all remained unchanged. The Lenape had no use for silver coins, nor for the bright silver trinkets of the white people; they had their own values, including the use of wampum. After 1600 wampum often was woven into belts, used for treaty with Europeans. The woven quill bands of the past had become more important than ever, and from them came the wampum bands which were even more significant.

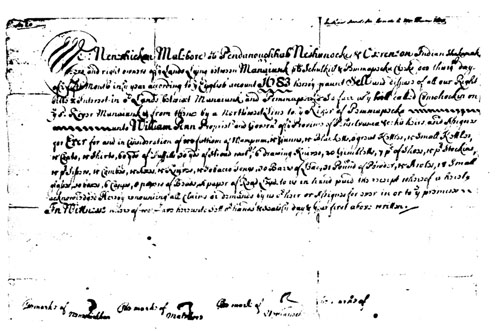

Wampum belt presented to William Penn By the time William Penn arrived on the Delaware River in 1682, many European settlements were already established. The shift from the fur trade to agriculture and to a more broadly based economy had been long in process. European and native American relations in the immediate area of the Delaware River were practically stable by 1682, when Penn began the systematic purchase of all native lands in the area of his grant. Lenape land sales to William Penn were in large blocks, which ultimately included all of their land holdings on the west side of the Delaware River, (in the Jersey colonies the purchase of land was not as systematic, leading to a very different pattern of living and integration.)

Penn's first treaty with the Lenape in 1683 The pattern in Pennsylvania had an important effect on the Lenape grantors, leading most of them to leave for the west. Despite Penn's commitment to protect Lenape rights on the lands which were not considered part of their sales (the lands on which they were "settled"), the Lenape need for space and hunting grounds led them to leave the area in large numbers. The Lenape Migrate to the West In a series of steps, clusters of Lenape moved progressively through western Pennsylvania, the Ohio River Valley, Indiana, and Wisconsin. By the middle of the nineteenth century the focus of intact Lenape culture was in Oklahoma, where many of the traditional Lenape had come to settle. Over the years other groups of Lenape also arrived in various parts of Oklahoma. The increasing density of European settlements following William Penn's arrival led to a significant reshaping of the Pennsylvania landscape after 1682. The great forests were cleared, lands were fenced, and fish runs were disrupted by mill dams. Many of the Lenape in Pennsylvania began to seek new lands in the west. Individuals, families, or small groups moved into the region formerly controlled by the Minquas. These newly formed Lenape bands shifted from exploiting food resources in the Delaware Valley to making a living along the streams and rivers draining into the Susquehanna River, a pattern which enabled them to maintain their traditional lifestyle in a new location somewhat similar to that which had been left behind. By the 1750's most of the Pennsylvania Lenape were living in the lower Allegheny and upper Ohio valleys, where they were sometimes co-resident with the Munsee, the Jersey Lenape Indians, and members of other cultures, who had also left their traditional homelands for a variety of reasons. These Lenape became the core of what became known as the "Delaware Tribe". The Lenape were politically far more closely knit after 1750 than they had been before. The loose alliance between disparate bands had been transformed into more organized units as a response to European-introduced conditions. The dispersed summer stations were replaced by small clusters of cabins and huts called "towns", each of which was informally led by (and named for) a specific "captain". By the 1800's most of the Lenape had purchased land in the Ohio Valley, where they established a number of these villages. Along with this growth in political unity came growth in the Lenape military power, which had been used effectively in the Carolina wars (c. 1720-1722), and then in the French and Indian War (1755-1763) and in all wars thereafter. The pattern of westward migration after this time often involved sale of the "old" lands and purchase of new lands from native groups still further to the west. Yet the Lenape still maintained the old ways, the men hunting for meat and fishing, and the women raising what crops they were able to. This pattern continued for over 100 years, ending only in Oklahoma, where the Lenape finally settled and became farmers and merchants. |