|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 23 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: April 1985 Volume 23 Number 2, Pages 55–61 The Military Achievements of General Anthony Wayne Anthony Wayne - next to the young Marquis de la Fayette the most brilliant and picturesque figure in the American Revolution - was born at Waynesborough in Easttown Township, Chester County, on January 1, 1745. The Wayne family was originally of English stock. The grandfather of the general was born in Yorkshire, but removed in his early manhood to an estate in County Wickham in Ireland. He was a Protestant and joined the forces of William of Orange in the contest with King James II. He commanded a troop of dragoons at the Battle of Boyne, for which service he was rewarded with lands in Ireland. For some reason, he sold his property in Ireland and came to Pennsylvania in 1722. He brought with him his four sons and also considerable property. In 1724 he purchased the Waynesborough property in Chester County, consisting of nearly sixteen hundred acres, on the border of the beautiful Chester Valley. Upon his death, this estate was divided among his sons, the youngest, Isaac, the father of the general, getting the home and five hundred acres. Isaac Wayne, who took great interest in the public affairs of the province, married Elizabeth Iddings, of Chester County. He died in 1774, leaving one son and two daughters. The son, Anthony, was a self-reliant boy. At an early age he was sent to school, his teacher being his father's brother, Gilbert Wayne, and the school house was known as the Wayne School, a log building located on the Wayne property. The boy worried his uncle in that he would not study the ancient languages, but preferred mathematics. His uncle, in despair, wrote to Anthony's father, "What he may be best qualified for I know not. He may perhaps make a soldier. He has already distracted the brains of two-thirds of the boys under my charge by rehearsals of battles and sieges. During noon, in place of the usual games and amusements, he has the boys employed in throwing up redoubts, skirmishing, etc." (We read of a like condition in the life of Napoleon!) Anthony's father, knowing there was no career for a provincial in the British Army, sent him at the age of 16 for classical training to a school in Philadelphia. But it too was rather hopeless, as such training simply did not appeal to the boy. Being fond of mathematics and the outdoors life, he took up a profession that resembled the life of a soldier, that of a surveyor, He soon gained quite a reputation in this work, for at the early age of twenty-one he was engaged by Dr. Franklin and other capitalists to survey a vast tract of land which they had recently purchased in Nova Scotia. He continued the work in the wilderness of Canada for almost two years. On his return home, he was married to the daughter of Bartholomew Penrose, a prominent merchant in Philadelphia, From that time until the outbreak of the Revolution he cultivated the farm at Waynesborough and established a tannery on it. When the first intimations of resistance to British ministerial measures were heard in 1774, he became a recognized leader in Chester County. As war with the mother country became more of a possibility, he undertook the raising of a regiment. The action of the Boston Tea Party was not looked upon with favor or approval in Pennsylvania, but everyone now saw what was coming, and Anthony Wayne became one of the most active men in the state in preparing for hostilities. By the end of 1775 the ranks of his regiment were filled, and on the recommendation of the Committee of Safety he was, on the third of January 1776, appointed its colonel, with Francis Johnston its lieutenant-colonel. During the winter of 1776 Wayne was at Chester, getting his men ready for active service. Colonel Wayne first saw military service in the expedition to Canada in the spring and summer of 1776, Wayne's command forming part of a brigade of Pennsylvanians commanded by General William Thompson. The brigade was composed of the second Batallion, under Col. St. Clair; the sixth, under Col. William Irvine; and the fourth Batallion, under Col. Wayne. The brigade was sent by Congress to reinforce the army under Generals Montgomery and Arnold, which had been repulsed at Quebec. The relief force reached a fort at the mouth of the Sorel, about halfway between Montreal and Quebec, on June 5, 1776, There they found a remnant of General Montgomery's army, which had retreated from Quebec. The British force, under General Burgoyne, was at Three Rivers, some distance down the St. Lawrence. General Sullivan ordered General Thompson to attack the British. It was Wayne's first battle, and he gave a good account of it in a letter to Dr. Franklin, It was largely through Wayne's efforts that the capture of the entire army was prevented and the retreat to Ticonderoga made possible.

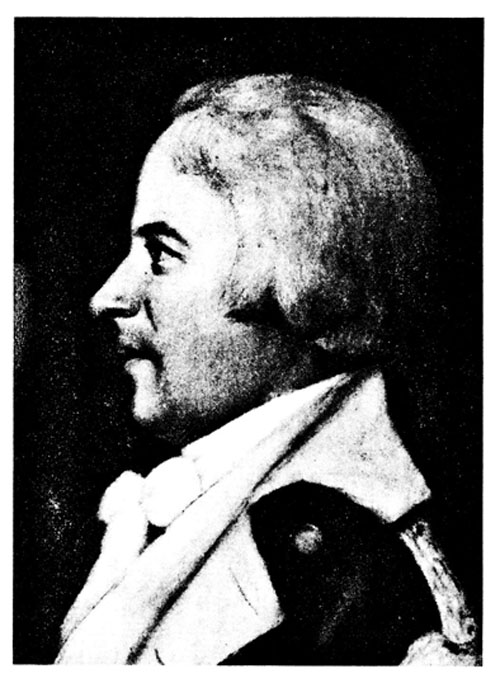

Major General Anthony Wayne General Thompson and Colonel Irvine having been taken prisoner at Three Rivers and Col. St. Clair having been wounded, the command of the Pennsylvania troops during the retreat from Sorel to Ticonderoga devolved upon Col. Wayne. At Ticonderoga, the army determined to make a stand. General Schuyler appointed Col. Wayne to the command of the fort on the 1st of November 1776; it was while Wayne was in command of the garrison that three months later, on February 21, 1777, he was appointed a brigadier general in the army. On April 12th he was directed by Washington to join him at Morristown, and he was at once placed in command of the Brigade known as the Pennsylvania Line. The British fleet, with Howe's army on board, sailed from Sandy Hook on July 25, 1777. Howe's destination was undoubtedly Philadelphia, to be approached from the south by sailing up the Chesapeake Bay. Wayne was sent by Washington to Chester County to arrange the militia there. The Continental Army marched through Philadelphia and took position near Wilmington on August 23, 1777 to await the British. Howe landed at the Head of Elk, and marched towards Chester County and Philadelphia. Washington met them at Chadd's Ford on the Brandywine, At the Brandywine, Wayne fronted the Hessian General Knyphausen and his seven thousand men, and stood his ground during the entire day. But after the right flank of the army had been turned by the enemy, Wayne was faced with Knyphausen in front and Cornwallis in the rear, and was forced to withdraw, which it did in good order. After the Battle of the Brandywine the British Army made its way slowly across Chester County, with the intention of fording the Schuylkill River near Swedesford and entering Philadelphia from the northwest. General Wayne was ordered to take post at the Paoli in order to attack the rear guard of the British in their camp in the Great Valley and, if possible, capture their baggage trains as they crossed the river. The position of Wayne's camp was betrayed to the British by the residents of the neighborhood. Wayne was attacked on the night of September 20, 1777 by a force under the command of General Grey; the "Paoli Massacre" resulted, in which sixty-one men were killed, out of Wayne's force of 1200. On account of the criticism to which Wayne was subjected, he asked for a court martial. The unaminous opinion of the Court Martial was "not guilty of the charges exhibited against him, but that on the night of the 20th of September last, [he] did every duty that could be expected from an active, brave and vigilant officer under the orders that he had. The Court do acquit him with the highest honor." The findings were approved by the commander-in-chief on October 4, at the dawn of the day on which Washington attacked Howe's army at the upper end of Germantown. Wayne was very conspicuous throughout the battle, which was almost won by the Continentals. In these three engagements - Brandywine, Paoli, and Germantown - in which Wayne's division was so conspicuous, his division was comprised entirely of Pennsylvania troops. Wayne's forces at no time during the campaign exceeded 1500 men. When the army went into winter quarters at Valley Forge, Wayne's main work was providing food and clothing for his men and filling up the depleted ranks of his command. It is pathetic to read General Wayne's letters written during the stay at Valley Forge - requests for clothing, shoes, medicine, food, no pay for the officers and men. How did they ever get through that winter? In one of Wayne's letters to Sharp Delaney, on May 21, 1778, he wrote, "The difficulty I experience in keeping good officers from resigning and causing them to do their duty in the line, has almost determined me to give it up and return to my Sabine fields, but I wish first to see the enemy sail for the West Indies." Want of money and its depreciation seem to have been the greatest trouble in the colonies. Early in June the British prepared to evacuate Philadelphia. The new Treaty of Alliance with France made the enemy desirous of getting out of the Delaware River before a blockade by the French fleet. When Sir Henry Clinton succeeded Sir William Howe as commander on June 8th, he found preparations for the evacuation far advanced. On June 18th the army left Philadelphia, crossed the Delaware below Gloucester, and marched eastward across New Jersey, their baggage train being twelve miles long! Washington followed, crossing the Delaware above Trenton on June 21st. On June 24th a Council of War was held by the Americans at Hopewell, near Princeton,, At this Council, Wayne was for prompt action: the idea of an army of 1200 men and a train of baggage twelve miles long going across New Jersey unmolested was too much for him! The Americans were more numerous, and so Washington decided to attack the British Army at Monmouth on June 27th. Wayne emerged from this engagement with a military reputation recognized by friend and foe of the patriot cause as one of the great leaders in the Revolution. The fervor in expressing praise for his service was unmatched in our history until Grant and Sherman and Sheridan! Washington said of him, "I cannot forbear mentioning Brigadier General Wayne, whose good conduct and bravery through the whole action deserves particular mention." The effect of this battle was deep and abiding. For eighteen months after the Battle of Monmouth, the American Army watched the enemy in New York, lest he make raids into Jersey, or go up the Hudson River. The army was drawn up in the form of a crescent, extending from Middlebrook in New Jersey to the Delaware to the south and, to the north, towards Long Island Sound. In August what remained of the three Pennsylvania brigades was formed into two, owing to the small number of recruits. In common with the whole army encamped at Middlebrook during the winter of 1778-1779, the Pennsylvania line suffered almost beyond endurance, not only from want of supplies of all kinds, but also from the payment of their wages in money of merely a nominal value. The British, in the meantime, managed to take possession of Stony Point on the western side of the Hudson River, and Verplank's Point on the eastern side. Washington was very desirous of recapturing these two forts, and in June 1779 Wayne was selected for this arduous task. After considerable survey of the locality, he attacked on the night of July 15th. The surprise was complete. Using the bayonet and without firing a shot, the garrison was taken and the dead numbered 63. "Our officers and men behaved like men who are determined to be free," Wayne wrote to Washington in announcing his success. Wayne's capture of Stony Point made a great sensation throughout the colonies, and he was congratulated in every quarter. The material gain was little, for the fort was soon afterward abandoned, but the morale effect was very great. The capture of Stony Point was probably the greatest single achievement of the Revolution. On February 26, 1781 Wayne was ordered to command a detachment of the Pennsylvania Line which had been designated as a reinforcement for Gen. Greene, then in charge of military affairs in South Carolina. The regiment assembled at York on May 20th. Much smaller in numbers than Wayne had thought, and poorly equipped, it began its march south. In the meantime, after the Battle of Eutaw Springs, Lord Cornwallis had made a rapid march and joined with General Phillips, who commanded the British troops on the James River in Virginia. On June 7th Wayne and his 800 men joined La Fayette at Fredericksburg. As this was the only American army in Virginia, it was LaFayette's and Wayne's objective to check the raids of the British into the interior of the country and to hold Cornwallis and his men near the mouth of the Chesapeake until Washington and the French fleet could arrive in the autumn. There was nothing particularly noteworthy in the part taken by Pennsylvania Line under Wayne at Yorktown. The truth is that the superiority in numbers of the Allies made the surrender of Cornwallis inevitable. Negotiations for the surrender were begun on the 17th of October, and on October 19, 1781 the garrison became prisoners of war and Cornwallis' army was no more. On November 1, 1781 Wayne was ordered to leave Williamsburg to continue his original assignment to reinforce General Greene's army in South Carolina. General Greene then sent Wayne into Georgia with a small force and instructions to re-establish, as far as might be possible, the authority of the United States within that state. In a short time he brought good order to the state, and Georgia showed her gratitude by giving out of her poverty 3900 guineas to purchase an estate for her deliverer, the rice plantation of James Wright, the last Royal governor of the colony, Wayne left Georgia in August 1782, having been ordered by General Greene to return with his forces to South Carolina to aid in the reduction of Charlestown. Almost immediately after his arrival in South Carolina hewas attacked by a fever from which he never fully recovered nor regained his full strength. In July 1783 General Wayne, after having seen the last of the Pennsylvania troops embark at Charleston for Philadelphia, returned to his native state, in shattered health. In October he was appointed by Congress Major-General by brevet. Wayne's estate in Georgia consisted of a rice plantation of nearly 830 acres. Not having the money necessary to run it, it was a failure, as he divided his time between his Pennsylvania property and his Georgia estate. The simple truth was that General Wayne was no business man. After the Treaty of 1783 the country north and west of the Ohio River was ceded by Virginia to the United States, and a territorial government was organized there in 1787. Every effort was made to induce people to settle on these lands, and especially soldiers who had fought in the Revolution, The country was being rapidly filled up, but the Indians of the northwest were determined that the whites should not occupy the region. Between 1783 and 1790 more than 1500 men, women and children had been killed. In addition, the British were still in possession of several forts north of the Ohio, refusing to comply with the Treaty of 1783. A large party in the United States was calling for war with Great Britain. The duty of the government was plain: the Indians must be subdued, but no foreign complications could arise. It was a situation that called for the highest military and diplomatic skills. There was but one man with the ability to handle such a position, and that was Wayne. In April 1792 General Wayne was appointed by President Washington to be Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. Wayne and his army moved to Cincinnati, and then north. Finally, on August 20, 1794 he won a decisive victory over the Indians at the Battle of Fallen Timbers. This battle settled for all time the ownership of that great tract of country bounded on the south by the Ohio, on the north by the Great Lakes, and on west to the Mississippi. It is not easy to overstate its importance in American history. In August 1795 General Wayne, having been absent from home for about three years, paid a visit to Pennsylvania. On his return he was welcomed everywhere; only a Roman General would have been given such a triumph. The Indians made a treaty at Greenville in August 1795, after which a treaty was concluded with England whereby the English were to turn over to the United States the forts of Niagara, Oswego, the Miami, and Detroit. In June 1796 Wayne was ordered to visit these forts and take possession of them in behalf of the United States, a task he executed with great tact and discretion. On November 17, 1796 he sailed from Detroit for Presqu'Isle, the site of the present city of Erie. He was very sick when he reached Erie, gradually failing until December 15th, when he died. Had he lived 18 days longer he would have completed his 52d year. Thus died one of the real leaders of the early Republic. Colonel Johnston said of him that "he was the strongest cohesive force in the Revolutionary army". On the north front of the monument in Radnor Churchyard is the inscription, "Major General Anthony Wayne, was born at Waynesborough in Chester Co., State of Pennsylvania, A.D. 1745, after a life of honor and usefullness he died in December 1796 at a military post on the shores of Lake Erie, Commander-in-Chief of the Armies of the United States. His military achievements are consecrated in the history of his country, and in the hearts of his countrymen. His remains are here interred". |