|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 25 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: April 1987 Volume 25 Number 2, Pages 41–46 Chester County Courts in 1786

The Courts in 1786 : Judge Leonard Sugerman In 1786 there were three separate county courts: The Court of Quarter Sessions, which was the criminal court; the Court of Common Pleas, which was the civil court; and the Orphans' Court, which settled estates. The Courts of Quarter Sessions and Common Pleas met four times a year, with terms beginning the last Tuesday in February, May, August, and November. Quarter Sessions terms usually lasted three days; Common Pleas terms usually lasted five days. The Orphans' Court was required to beheld four times a year, but was actually held more often, as the need arose. Orphans' Court terms usually lasted one day. Adjourned sessions of the Court of Common Pleas were sometimes held between regular sessions in order to transact miscellaneous court business. County justices of the peace met collectively and held the county courts. The office of county judge, as distinct from that of justice of the peace, was not created until 1790, when the Pennsylvania Constitution of that year was adopted. In the eighteenth century it was common for one man to serve as clerk of all the courts. The clerk in 1786 was Caleb Davis. He was, incidentally, a prominent opponent of the removal of the county seat from Chester to West Chester. TopThe Court of Quarter Sessions : Judge Thomas Gavin The Court of Quarter Sessions heard criminal cases and also oversaw various county administrative functions. No person could be tried for a criminal offense in the Court of Quarter Sessions without having the grand jury first having returned a true bill of indictment against him. The grand jury generally consisted of from 12 to 24 men and met each court session. It reviewed the facts in a criminal case and determined if there was sufficient evidence to bring the case to trial. If there was sufficient evidence, the case was tried; if not, the case was dismissed. Criminal cases were prosecuted by the deputy attorney general. The office of district attorney was not created until 1850. The most common criminal cases in the late 18th century were assault and battery, larceny, fornication and bastardy, horse stealing, and operating a tavern without a license. The Court of Quarter Sessions administered the licensing of taverns. Taverns played a vital role in early Pennsylvania, providing food and lodging to travelers and serving as local public meeting establishments. A person wishing to operate a tavern petitioned the Court. After considering the petition, the Court recommended (or did not recommend) to the Governor that the individual be granted a license to operate a tavern. County court administration of tavern licensing lasted until prohibition; after prohibition was repealed, the state took over this function. Serious crimes (murder, rape, treason) were tried by the judges of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, sitting as a Court of Oyer and Terminer and General Jail Delivery. County courts did not hear serious crimes until the 1790 Pennsylvania Constitution allowed them to do so. The Court of Quarter Sessions also oversaw the laying out of roads and bridges. If an individual or group of individuals wished a road or bridge built or an existing road vacated, he/they petitioned the court. The court would then appoint a committee to investigate the matter and report back to the Court. Based on the committee's report, the Court allowed (or did not allow) the road or bridge to be built or the road vacated. The Court of Quarter Sessions also heard disputes involving apprentices and indentured servants. Apprenticeships and indentured servitude were very common in early Pennsylvania. A young man or woman would be bound to a master for a specific period of time, either to learn a trade or to pay off a debt. There were often problems with these arrangements and the Court had jurisdiction in matters involving runaway servants, cruel masters, female servants becoming pregnant, and other disputes. The Court of Quarter Sessions heard cases involving care of the poor. Each township or borough was responsible for the care of its poor citizens, and the overseers of the poor in each municipality levied a tax on the inhabitants for this purpose. When a poor person traveled from one municipality to another, the two municipalities often entered into a dispute regarding which one was responsible for the care of the individual. These disputes were settled in the Court of Quarter Sessions. The County built a poorhouse in 1800, at which time the practice of caring for the poor by the individual township or borough was discontinued. The first Court of Quarter Sessions to sit in West Chester was held on November 28, 1786. The entry in the docket for this Court term reads: "The court of General Quarter Sessions of the peace and goal [jail] delivery held and kept West Chester for the county of Chester the twenty eighth day of November anno Domini 1786, before William Clingan, William Hazlett, John Bartholomew, Philip Scott, Isaac Taylor, John Ralston, Joseph Luckey, Thomas Cheyney, Thomas Lewis and Richard Morris Esqr. Justices present and from thence continued by adjoinments till the thirtieth day of the same month inclusive." During the November 1786 term the Court considered 20 cases: nine were for assault and battery, four were for larceny, two were for fornication and bastardy, two were for horse stealing, one was for keeping a tavern without a license, one was for perjury, and one was a case between the overseers of the poor of East Whiteland and West Whiteland townships. Of these 20 cases, eight defendants were found guilty, none was found not guilty, one case was dismissed (the grand jury not finding sufficient evidence), and eleven cases were continued until the next court term. The sentences for the guilty included: for horse stealing, pay fine of £20 and be taken to public jail and serve 3 years and be kept at hard labor, including "making and repairing and mending the public roads and highways within this County"; for larceny, pay fine and costs of prosecution and be whipped the following day with 21 lashes on his bare back "well laid on"; for fornication and bastardy, pay fine and costs of prosecution, pay mother of bastard child a sum for "lying in" [that is, expenses incurred in giving birth], pay certain amount per week until the child reaches a specific age, indemnify the township where the child lives so he doesn't become a public charge, and be jailed until the sentence is complied with. TopThe Court of Common Pleas : Judge Charles Smith The Court of Common Pleas was the civil court. The overwhelming majority of the cases heard in this court in the late 18th century were debt and trespass cases, trespass in this context meaning the recovery of damages resulting from the wrongful act of another. If, as a result of a court judgment, you owed someone a debt that you could not pay, you could be thrown into prison. However, you could petition the Court of Common Pleas for release from prison under the benefit of the insolvency laws, a common procedure in early Pennsylvania. If you owned property, such as a farm, the Court of Common Pleas ordered an inquisition. The sheriff and a jury of 12 men went to view your property to determine if its profits were such that you could pay off the debt within seven years. If the inquisition found that the profits were of sufficient value to pay the debts within seven years, you were allowed to keep your property and pay off the debt. If the property was not of sufficient value, your land was sold by the sheriff and the proceeds given to your creditors. Many civil disputes in the Court of Common Pleas were resolved by rule of reference, in which the matter in controversy was referred to three arbitrators. These men heard testimony, reviewed the facts, and rendered judgment. Their judgment was considered as valid as that of the Court. There were certain things that the Court of Common Pleas does now that it did not do in 1786. The Court did not begin to admit persons to U. S. citizenship until 1798. The Court did not begin to grant divorces until 1804. The Court did not have full equity powers until 1857. The first Court of Common Pleas to sit in West Chester was held November 28, 1786. The entry in the docket for this term reads: "At a court of common Pleas held and kept at West Chester for the county of Chester the twenty eighth day of November Anno Domini One thousand seven hundred and Eighty six before William Clingan, William Hazlett, John Bartholomew, Philip Scott, Isaac Taylor, John Ralston, Joseph Luckey, Thomas Cheyney, Thomas Lewis and Richard Hil Morris Esqr. Justices present, And from thence continued by adjournments untill the second day of December following inclusive." Two hundred sixteen matters came before the Court during the November 1786 term. Most were debt and trespass cases. There were also two ejectment cases, in which a landowner sought to have people unlawfully living on his land ejected from the land. The Court also acknowledged the execution of a Sheriff's Deed at this term; the Deed was for a property sold by the Sheriff. An adjourned Court of Common Pleas was held three weeks later, on December 19, 1786. At this court, four insolvent debtors who had petitioned the Court for release from debtor's prison were discharged from confinement. TopOrphan's Court : Judge Lawrence Wood The Orphan's Court oversaw the settlement of estates. The name is a misnomer as the Court handled much more than cases dealing with orphans. Orphans' Court often met at places other than the courthouse, such as in private homes or in local taverns in various parts of the county. In 1786 Orphans' Court was held 12 times: 8 times in Chester, one time in West Chester, and three times in private homes. Matters that came before the Orphans' Court included the partition of lands to be divided among the heirs of an estate, the sale of land out of an estate, the appointment of guardians for minor children, the confirmation of auditing of accounts of administrators or guardians of estates, and the awarding of pensions to soldiers who fought in the Revolutionary War. If a landowner died intestate (without a will) or did not leave clear instructions in his will regarding the land, the Orphans' Court had jurisdiction over the division of the land. In order to distribute the land properly among the heirs, the court ordered an inquisition. The sheriff and twelve men viewed the property and decided if and how the land was to be divided. If they determined that the land could not be divided without "prejudice or spoiling the whole", the land was appraised and offered for sale to an heir. The order in which the heirs were offered the land was specified by law. The heir who took the land then paid the remaining heirs for what would have been their shares. The Orphans' Court also oversaw the sale of all or part of the lands out of an estate. If a deceased landowner had debts, or if money was needed to support his family, the land could be sold by approval of the court. The Orphans' Court appointed guardians for minors (those under the age of twenty-one) who were to receive property out of an estate. If the child was under the age of fourteen, a relative or friend petitioned the court to appoint a guardian. A minor who was fourteen years or older submitted the name of the person he or she wished to have as guardian. The court then approved or disapproved the minor's selection. The guardian received and supervised the minor's inheritance. If it was land, it was usually rented out and the money put out at interest and used to support the minor. A minor did not have to be an orphan to have a guardian. Also, if the minor's father was deceased, the minor's mother was usually not appointed guardian of the minor's estate. The mother often received support payments from the guardian to cover expenses incurred in raising the child. The first Orphans' Court to sit in West Chester was held on December 19, 1786. The entry in the docket for this term reads: "At an orphans court held and kept at West Chester for the County of Chester the nineteenth day of december anno dom one thousand seven hundred and eighty six Before William Clingan, John Bartholomew, Dan Griffith, Thomas Levis, Thomas Cheyney and Isaac Taylor Esqs. Justices present." At this December 1786 term 10 matters came before the court: five guardians were appointed for minors, two inquisitions on land were returned, one account of the administrator of an estate was confirmed by the court, and two Revolutionary War soldiers were awarded pensions. One of these pension cases reads from the docket as follows: "Thomas Owen, late a private soldier in Captain Joseph Pott's company of the Fifth Pennsylvania Regiment commanded by Colonel Francis Johnston, aged fifty two years, made appear to this court that he received a wound in his right thigh by a musket ball shot through it at the Battle of Brandywine on the eleventh day of September, anno Domini one thousand seven hundred and seventy seven. "It is therefore considered and adjudged by this court that he is entitled to a pension of one Dollar and a half per month commencing the fifteenth day of August, one thousand seven hundred and eighty five."

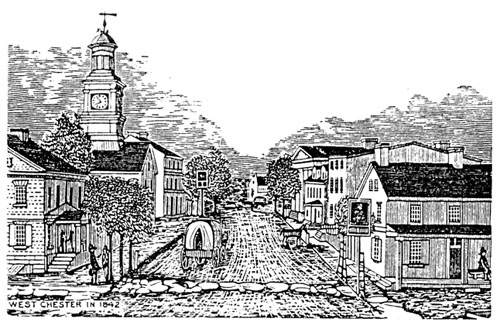

The 1786 Court House in West Chester from a woodcut of West Chester in 1842 |