|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 25 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

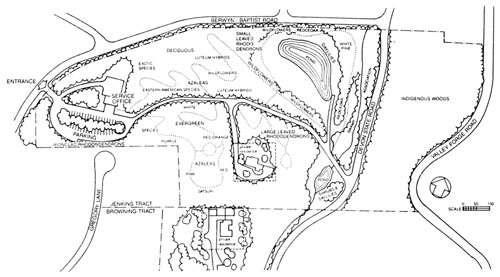

Source: October 1987 Volume 25 Number 4, Pages 121–127 The Jenkins Arboretum The Jenkins Arboretum opened to the public in 1976, and covers 46 acres of ground. The twenty acres on which it first started were formerly the home of H. Lawrence Jenkins and his wife, Elizabeth Phillippe Jenkins. They were not famous, and they were not wealthy, and I think that really makes the Jenkins Arboretum quite exceptional. If you look at other arboreta -- the Morris Arboretum, the Tyler Arboretum, Longwood Gardens, Winterthur, the Barnes Foundation, even Swiss Pines -- they were started by either wealthy or famous people. What we have here is a couple who were basically just of modest means. There was some money on Mrs. Jenkins' side of the family--they had some gardeners, they had an occasional chauffeur, they had a maid -- but they were not considered wealthy, and the foundation was started with a very small endowment. And that is one of the things, I think, that makes the Jenkins Arboretum unique. Even though the Jenkinses were not famous and were not wealthy, look at what they created for the community! Some of you probably know more about the history of the Jenkinses than I do. I simply have not been able to go through all the historical material that we have, or to put together a good historical account of the family, because I am so busy trying just to keep up. I am the only full-time employee, and you can imagine the problems of keeping up with the growing plants, doing the administration, the fund raising, and all the maintenance. In fact, in a way this is sort of a solicitation: if anybody has a special interest in the Jenkins family history, we have a whole box of photograph albums, scrap books, birth certificates, old topographical maps from the 1920s, a nice batch of family photographs and documentation, all good raw material. (The 1920 topographical map, incidentally, shows that a wagon trail went back at an angle from Berwyn-Baptist road, behind the Jenkins' house, and across to Devon State Road; it is listed as a wagon trail, and the contour lines show ruts.) But we do know that Mr. Jenkins was born in 1890 and died in 1968. He was in the British Merchant Marine. I am not sure whether or not he was a submarine captain in World War I, but among his memorabilia there are numerous photos of a submarine and a model. Mrs. Jenkins was a Pemberton, and the Pembertons were an old monied Philadelphia Quaker, family. Her father, B. Pemberton Phillippe, was a minor official with the Pennsylvania Railroad, and purchased the house and grounds in 1927. She was a French-Canadian, and when she met the dashing young merchant marine he swept her off her feet, or at least that is how the story goes. They did not have any children. Somehow Mr. Jenkins became invalided from about the time of World War I on, so he was pretty much incapacitated and unable to walk around. But Mrs. Jenkins took an active interest in gardening and the wildlife in the area. She maintained a whole array of bird feeders throughout the property, numerous bird baths, and loved nature. I think it is really romantic that, when she died Mr. Jenkins started a living memorial to his wife -- and that is what we have here in the Jenkins Arboretum. In his will he directed that the property become "a public park, arboretum, and wildlife sanctuary for the use by the public and responsible organizations engaged in the study of arborculture, horticulture and wildlife for educational and scientific purposes". So it was Mr. Jenkins' love for his wife that created this arboretum for the community, and I think that is very special. When Mr. Jenkins died, after his wife, in 1968, the First Pennsylvania Bank was picked as the trustee, and it still is. As trustee, the Bank commissioned the landscape architect George Patton to survey the site and to see what could be developed here without disturbing the natural ecology too much. I think that we have struck a rather nice balance of natural and horticultural plantings. We took plants mostly in the Ericaceae (heath) family, a group of mostly acid-loving plants. It includes rhododendron, azaleas, mountain laurel, pieris, blueberries, dangleberries, bearberries -- there are a lot of plants in the Ericaceae family that one might not realize are in this acid-loving family. We are definitely in an acid soil here, about pH 4.4 (7.0 is neutral), so everything we planted, even the hollies, are acidloving. We picked plants well suited to the site. We also left the native woodland wild flowers -- the Jack-in-the-pulpits, the May apples, ferns, and so on. We are really well on the road to being a serious botanical garden/arboretum.

The whole property is surveyed out into a 50' by 50' grid; there is a marker post every 50 feet. Every plant is mapped. It is given a label, an accession number so that we can determine when it was acquired, its origin, its common name, its variety, its cultivar. (The next job is to get all this on a computer, because I am shuffling index cards all the time. You know how hard it is to keep a list up-to-date: you make an addition to it and you have to make a new list. So my goal is to get a computer to update the records.) We have extensive wildflower collections -- over 250 wildflowers in all. Every effort has been made to label them with both their common names and their scientific names. We have also labelled as many trees as possible. We have almost 70 different species of trees, all native. When you visit places like Longwood Gardens, the Tyler Arboretum, or Morris Arboretum you'll find many exotic trees from all over the world. Here they are almost all native trees; we have five or six kinds of oaks, beeches, two kinds of cherry, birches, tulip-poplar, maples, the list goes on and on. Like everyone else, we have had a problem over the past few years with the native dogwoods. I have talked with a plant pathologist at Rutgers University, and he said that among plant pathologists the feeling is that the dogwoods are not going to die out, and the disease is not going to destroy them all. What has happened is the compounding effect of stress -- the gypsy moth defoliation and multiple years of drought. They weaken the tree, and then it succumbs to the fungus that has been there all along. But this year the dogwoods had stupendous flowers; they bloomed for five weeks. They looked pretty good this year, and it is the general consensus that the dogwoods are going to be with us. The Jenkins Arboretum has a lot of native plants, and this too makes us sort of unique because there is a tendency to shun what is in your own back yard. But native plants are of botanical interest - and would be exotic to someone in England or Japan, for example. If one is receptive and observant, they too are simply fantastic! Most of the azaleas and rhododendrons have been planted within the past twelve years. Almost all the plantings were established by my father, Leonard Sweetman, who was the Director from the very beginning and until his retirement in October 1986. When the arboreturm first opened in 1976 there was a "grand opening", with a band and a big celebration and a lot of publicity -- and the plants were all about "gallon" size, eight to ten inches tall. The plantings were in groups of three to six of the same variety. Even though there were some 2000 or 3000 plants, it really did not look stupendous. A lot of people have not been back since! Now we are getting some nice publicity -- there was an excellent article in the Local this spring [May 17, 1987] describing the place as a "jewel". It really is a small jewel. We are not big, just, a manageable size. You will not find bittersweet, poison ivy, Japanese honeysuckle, wineberries, or wild garlic here, because they are either foreign invaders or pestiferous. Most were not native to this area, and even though we have established naturalized horticultural plantings we have also kept a little of the old ecology that you will not find once you go beyond our fences. Actually, we do have one specimen of poison ivy, we have one example of Virginia creeper, and so on -- for educational purposes. But by and large we do a really good job of beating back the jungle, because most of the jungle is foreign and was not supposed to be here. The Jenkins' house is a part of the arboretum and is located near the middle of the property. It is stone, and was built in 1929, just before the Depression, and is a quality construction job. It has never been repointed, and the stone is in remarkable shape. It has full 3" by 4" framing and is well plastered. (Some of the plaster is over one inch thick.) When it was built it was located so as to have a view out over the valley. Now the woods and trees have grown up, but in the winter you can still see completely across to Valley Forge Park; you can see the bell tower and the Chapel. The sun room, a large solarium, is on the north side of the house because they wanted to see the view out over the valley from it; today that would be considered backwards and it would be put on the south side. Six years ago there was a fire -- a log rolled out of the fire place -- and one end of the house was damaged. It burned a hole through the floor of the living room, but fortunately did not damage the upstairs and the second floor. The house is presently undergoing a complete restoration and will become the Director's residence. The portico and adjacent rose garden will also be used to host small receptions pertaining to functions of the Arboretum. Mrs. Jenkins had a number of old-fashioned climbing roses, the kind that you have to trellis up about twelve feet in the air. They are really a maintenance problem! Today most people purchase hybrid roses that are simply pruned to the ground every year. Those big climbing roses have to be trellised to get nice blooms; if you do not trellis them they run horizontally, and that can become a disastrous tangle. The canes are woody and can be as much as an inch in diameter, and from them come multiple branches that flower. The Jenkins property had about 20 acres, about five of them across Devon State road. So we have actually developed about 15 acres. But even that is a lot to take care of. The Browning tract, to the south, is about 26 acres; it was donated to us by Louisa Browning in 1971. The Browning property provides an excellent buffer against the surrounding developments and expands the feeling of being surrounded by nature. It will be used in the future for arboretum expansion, nurseries, plant-breeding programs, and research. When the idea of this arboretum was first conceived there was not this scale of nearby development and there was less noise. But you know what Devon State road is like today; at rush hour you cannot hear a bird anywhere down by the stream and pond. I think we need to put up some visual screens, and I would like to interest the State in putting up a sound barrier, because the place really deserves it. Even though we own the property across Devon State road, I don't think we will do much development there but rather will preserve it as a view forever. Since it is our property you will never see a house there. It will remain woods, indigenous woods, and in a hundred years it will still look like the virgin forest -- even though it is in the midst of massive development. The Browning house also has some historic significance. It was an old log cabin that, I think, was later partially reassembled. It is attached to a mud-mortared barn; at least I assume it was a barn because it was mud-mortared. Still later Brognard Okie, the architect, did a total restoration, remodeling both the cabin and the barn and attaching what is now known as the Browning house to them. He tied it all together very nicely, and it is very interesting architecturally. We are doing an excellent job at maintaining the property, which is now used as part of our staff housing. (We have two part-time staff, and we subsidize them with housing. I am also living there temporarily.) The Arboretum has a small identity problem, because most people assume that we are funded by the township or other governmental agencies. We are not. Although we are a part of the Tredyffrin Township Park System, we are totally supported by the private foundation that was set up in Mr. Jenkins' will. As we become more publicized and better known in the community I think we will start to receive financial contributions, donations, and more corporate support. We could solicit tax money, but I think it is better to stay a private foundation like we are and to rely on the community for support. We certainly are surrounded by a high density of corporate headquarters, and I think in the future we will receive corporate support. Most of our educational programs are passive. We try to label the plants and trees and we have a self-guided nature trail, so if one in interested there is a lot to learn. But we do not provide a lot of active programs. Obviously, we do not have the staff to go around to the schools, although I do talk to garden clubs and other organizations whenever possible. Our job is to be a display arboretum, and that is what we are well on our way to being. We do host the entire toxology course from the Univeristy of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, however. It is required to come here and study the poisonous plant collection. (This makes it sound like we put a lot of effort into poisonous plants, but the fact is that many plants are poisonous. Even many household plants are poisonous! To a puppy or a small child, eating poisonous plants or seeds could be fatal; to an herbivore who consumes large quantities of plant material they may also be fatal. But to humans, most poisonous plants are distasteful, and so they are no real problem. Take something like pokeweed. Some of you may have eaten a polkweed and enjoyed it -- you boil it twice and you eat it -- but if an herbivore eats pokeweed it can be deadly.) So we had 110 veterinary students descend on this place one afternoon in early May, and we went around and identified the poisonous plants. They have to know them because they are going to have to deal with animals that have eaten them. Over the years we have become a regular part of their toxology course. But the plants we show them are actually just a part of our wildflower collection. We do get volunteers from the Boys Scouts from time to time to help us in maintenance work. I have several volunteers from Devon Troop 50, Scouts who are working on their Eagle project. The bridge down at the bottom of the hill as built by an Eagle Scout. This past spring I had four boys that went around and for eight hours we picked leaves off the azaleas. You can imagine, with the tree canopy, how the azaleas just get buried in leaves, which is fine in the wintertime because it gives them some protection from the harsh winter, but come spring, we have to go around and handpick all the leaves off some 4000 plants! I was pleased to have the Boy Scouts to help, even though some of them sort of frowned, and it was necessary to poke them and keep them moving. I taught them to work a full eight-hour day - but I do not think any of them has been back since! As a buffer or screen along the edges of our property we have planted hundreds of native rhododendrons, but we have to wait for them to grow. We planted Rhododendron maximum, the wild rhododendron which grows to be 10 or 15 feet tall, and we have them and hollies all along the borders where developments have been built up. So in time the property will be pretty well screened. They were planted about a dozen years ago, and might have been three or four years old when they were planted and only 18" to 24" tall. While they are young you can almost determine their age by the branching pattern: every year they send out a shoot, so you just back track and count back the bifurcation. (They are similar to a pine tree: you count the whorls of branches on a pine tree, add one year for the seedling and one year for the single shoot at the top, and you can tell its age.) Rhododendrons live to be 100 or 150 years old. In the Smokey Mountains in North Carolina there are thickets of rhododendrons where the trunks are six inches in diameter, and there are tree rhododendrons in Nepal and the Himalayas that are really trees and they make logs out of them. I am asked from time to time about the effect of acid rain on the arboretum. Every time it rains I measure the rain and check it for pH. The amount of acidity in the rain here has varied from about 4.5 to 6.0, and even down to 6.8 or 7.0. Depending on the storm track and the cloud conditions, there is a lot of variability in the pH. Actually, the pollutants that are causing acid rain are acids of sulfur and nitrogen, two basic nutrients of all plants, so, basically, acid rain is in effect fertilizing them. The only places that plant damage from acid rain has been demonstrated is on mountain tops, in places like northern Vermont. There, the current theory is, the trees in acid clouds are being foliar-fertilized. The nitric and sulfuric acids are thus feeding them throughout the year, and as a result the trees are growing at the wrong times of the year, sending out new growth in the late summer and early fall that is not winter hardy and which stresses the tree. I am for stopping acid rain, but as a horticulturist here in Pennsylvania growing and loving plants, it probably has no significance. But we sometimes have a problem with wildlife. While the arboretum is basically an ecological unit, wildlife -- especially raccoons -- can play havoc with the plantings. We once had some Canada geese that flew into the pond, and in one afternoon they nibbled away about $165 worth of water lilies that we had planted there. They made a nest in the wild iris, and in two days there were three eggs, and the iris was fast disappearing! I hated to do it, but we had no choice but to scare them away -- waving at them, making noises, shining lights on them until they left. One thing we are thinking about is starting a "Friends of the Arboretum". We do not want to charge admission, and I do not think that we even want to have memberships. But we would like to have more people and corporations know about us and support us because the Jenkins Arboretum is here to serve the community. The entrance to the Jenkins Arboretum is at 631 Berwyn Baptist Road, just above the intersection of Berwyn Baptist and Devon State Roads. Admission is free, and the Arboretum is open throughout the year during daylight hours, from dawn to dusk seven days a week. |