|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 27 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 1989 Volume 27 Number 3, Pages 83–92 Yellow Springs Yellow Springs is a living village, steeped in such distinguished history, tradition and folklore that it stirs the imagination of the many diverse groups of people that visit the property each year. It spans more than 250 years of our nation's history.

Today we see the history of the property in six distinctive periods: This last phase is an exciting one! We today are continuing the history of this special village in a most meaningful way. The charter of Historic Yellow Springs, Inc. mandates the conservation, preservation, and adaptive use of the property in ways that will be most beneficial to community life. Historic Yellow Springs is committed to create and maintain a center for the encouragement of activities and programs related to history and the arts, the conservation of its cultural history, and the nurture of its aesthetic and physical environment. We are really an "open-air" museum. We don't have a "house" museum or furnished rooms for visitors to see. We don't rope off areas or ask you to stay behind barricades to look at what happened here. Things are still happening! Families still live here next to our historic sites; the Inn at Yellow Springs is still a public dining facility. Many study art at the Chester Springs Studio. Creativity in all its phases continues at the Yellow Springs Institute, and the Chester Springs library is rapidly expanding as a library center. (In fact, the library has just been chosen as a model for the Chester County Library system.) We hope that you can share in the excitement, in the vital, evolving place the village of Yellow Springs is, and in the importance of our organization and its work in preserving and restoring its historic heritage. The roots of Historic Yellow Springs, Inc. began in 1966 when the Yellow Springs Association was formed to bring culture to Chester Springs and to help preserve the village and conserve the surrounding land. The Good News Productions, a motion picture company, supported the concept, and promoted the program by providing space for activities. In 1971 the property was listed on the National Registry of Historic Places. The Yellow Springs Foundation was formed in 1973, with the task of buying the property when it became available for sale. Through contributions and carefully planned financing, the site was purchased. Three years later, in 1976, the Yellow Springs Association and the Yellow Springs Foundation merged to form Historic Yellow Springs, Inc., a Pennsylvania non-profit cultural trust. This organization is supported through memberships, a total of about 500 at the present time, rental income, fund raising through both government and private grants, and various programs and events. These include the art show in the spring -- one of the largest in the mid-Atlantic region -- an antiques show in October, a craft festival in June, and an annual Frolicks, a dinner-dance, also in June. The programs also include summer workshops for children, and lectures and community open-house programs to interpret specific sites and projects within the village. So far, Historic Yellow Springs, Inc. has completed restoration of the Iron Spring gazebo in 1976; restoration of the exterior of the Lincoln Building in 1984; and in 1988 a total restoration of the Jenny Lind Spring House, which we celebrated with a Jenny Lind concert. This summer we will begin restoration work on the Diamond Spring House, and plans are currently underway to complete restoration of the interior of the Lincoln Building. Two private residences within the village, owned by our organization, are also undergoing restoration at the present time. The National Register status of the village mandates that we complete our restoration work in certain ways and insures the preservation of the historic integrity of all structures. We have also entered into a specific lease arrangement with the Inn at Yellow Springs that has resulted in the restoration of the Washington Building as a fine eating establishment.

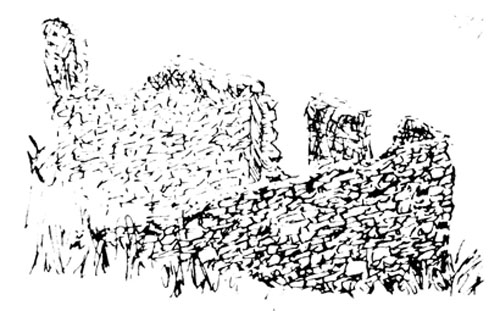

Ruins of the Revolutionary War hospital The largest, and a very significant, project has been underway for the past two years: it is the preservation and stabilization of the Revolutionary War hospital ruins. The project began back in January 1987 when the site was freed from the bush and forest undergrowth that surrounded it. This phase was completed when a new walkway was constructed to the site and a magnificent 18th century herb garden was established. This most generous gift was presented to Historic Yellow Springs by the Philadelphia unit of the National Herb Society, and is lovingly tended by its members. They researched all the plant materials to assure their authenticity to the historic period. When we celebrated this venture the project was designated as one of the programs of the WE THE PEOPLE 200 celebration of the bicentennial of the U. S. Constitution. At the same time the total hospital site was recognized as a memorial to all who had served and suffered here. The second phase began this past January and should be completed shortly. It involves working with the masonry. We rebuilt the entire back wall with field stones from the original deteriorated wall still at the site, and presently all the stonework is being capped and repointed using the correct historic methods. Preserving ruins is an innovative venture for historic preservationists. In most cases ruins are either just torn downor are torn down and then the original structure is reproduced. With guidance from a professional historic consultant, we saw the value of preserving them as a valuable artifact in themselves. It can be viewed as "above-the-ground" archaeology, and we learned additional data about the site as this preservation work progressed. We found, for example, a fire place and other window openings, as well as additional foundations to the east of the main structure. We hope you will come visit our Revolutionary War Hospital Memorial and the 18th century Medicinal Herb Garden. But now let me tell you something about what occurred here in 1777-1778. In a sermon from the Forks of the Brandywine in Chester County, the Presbyterian minister the Rev. John Carmichael said. We have all the true friends of virtue, of liberty and righteousness on our side. We have all the angels of heaven on our side, for we have truth and justice on our side. . . . Courage, my brave American soldiers! If God be for, who can be against you? However, George Washington and the Continental Army found many instances in 1777 to doubt this statement. One area of confusion, misconduct, and disorganization was the Medical Department. In his Crisis, Thomas Paine wrote, "These are the times that try men's souls", to which Joseph Plumb Martin, a Continental soldier, added "I often found that those times not only tried men's souls, but their bodies too. ..." (Since a full report on "Medicine in the Revolutionary War" was given by Dr. Skip Eichner in the July 1988 issue of the Quarterly [Vol. XXVI, No. 3] I will refrain from going into detail a second time except in those instances where it is necessary to complement my remarks.) As you know, when General Washington took command of the Continental Army at Cambridge, Massachusetts on April 16, 1775, there was no semblance of an organized medical department. There were in fact only about 3500 physicians in all the colonies, and no more than about 400 of them had medical degrees. (There were only two medical schools in the colonies: in 1766, doctors John Morgan and William Shippen opened the College of Philadelphia Medical School [now the University of Pennsylvania]; and two years later King's College in New York [now Columbia] established the second medical school in the colonies.) The principal formal training centers for physicians had been Edinburgh, London, and Leiden, but the majority of "doctors" received their education by serving as apprentices. In the absence of a medical department, medical supplies were distributed to the army from a warehouse in Reading under the direction of Dr. Jonathan Potts, while Dr. D. A. Craigie prepared and issued drugs from Carlisle. Chests containing medicine and instruments, sometimes called the "apothecary ration", were issued to regimental surgeons. Many jealousies and altercations occurred between surgeons; supplies were short; and problems continued to escalate. Washington called the situation "a disgrace to the profession, the army, and the society". Yet no one could really be blamed. No one was experienced in the various phases of military medicine. It was a field without precedent in the colonies. To help correct the situation, Washington reorganized the medical system. He set forth a chain of responsibility, and increased salaries. He also established four medical districts. (The Middle District included New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Delaware and Maryland.) Three types of hospitals were established: general hospitals, operated by the Continental Medical Department, located in private homes, barns, or churches and other public buildings; flying hospitals, manned by Continental military personnel as spring/summer operations, following the campaigns and mobile, located intents or huts; and regimental hospitals, managed by the regimental surgeon and mates in private homes or in huts at a winter encampment, to treat minor diseases. A general hospital was established at Bethlehem in the Single Brethren's House of Moravians, a religious sect. Here are accounts of its activities after the Battle of Germantown: Wounded soldiers poured down upon them. Day after day they were brought here. A month later an entire train of groaning officers and men had to be sent on to Easton because there was no longer room for them in Bethlehem. Four hundred were in the Brethren's House and fifty in tents, yet still field dressing stations continued to direct their wagons laden with wounded to this island of mercy. Townspeople gave all their supplies and blankets and clothes to help. After the Battle of Germantown the number of patients had included far beyond the capacity of the staff of surgeons and nurses. Still they came and were told to continue to Easton and beyond. Some were so near their end they could not be taken further. Some of these newly arrived were laid upon the ground in the rain to die. Some were taken to private farms further on. Other hospitals were located in such places as Skippack, Easton, Allens Town, Ephrata, Lancaster, Lititz, Reading, and other places, but these "hospitals" were actually just houses, churches and barns used on a temporary basis. All the hospitals were overcrowded, the staff overworked and under-supplied. Typhus sufferers were placed along side convalescents or wounded men. Four or five patients died on the same straw before it was changed. The death rate continued to escalate. With 2898 of his 11,000 troops at Valley Forge unfit for duty due to illness or lack of clothing four days after their arrival at the winter camp site, Washington desperately addressed Congress, noting that "Without adequate provisions, the army must inevitably ... starve, dissolve, or disperse." To alleviate the medical situation, he also suggested that a building especially designed as a hospital be erected. With small pox again threatening the troops, he wanted the contagious diseases to be addressed along with the other ailments that were increasing. Actually, many advised against a hospital; Dr. Benjamin Rush, for example, wrote that he hoped the progress of science would abolish some day the hospital for acute diseases, and described them as "sinks [and] cesspools of human life". Nevertheless, Congress approved Washington's plan, and Washington proceeded with plans to build a hospital building. Dr. Samuel Kennedy, a local physician and surgeon to General "Mad Anthony" Wayne's Fourth Pennsylvania Battalion, offered his land at Yellow Springs as a site for the hospital. He had purchased the property in 1774. The property was a popular spa, known for its mineral springs which were recommended to cure palsy, nervousness, rheumatism, and "all complaints showing debility and langour". It had operated as early as in 1722, and as early as in 1760, travelers from as far away as the West Indies were coming to the springs. No longer a primitive spa, a hotel, bath houses with drawing rooms and fireplaces, other suitable buildings, and barns existed at the site. The offer was accepted. Construction began in January 1778 and "Washington Hall" became the only specially designed hospital erected for the soldiers of the Continental Army, with the exception of the small log huts of the flying hospitals. The building was 106 feet long, 36 feet wide, three full stories and attic high. Nine-foot porches surrounded the first two stories on three sides. The first, or ground, floor had a kitchen, dining room, and utilitarian quarters. The second floor was divided into two large wards, while the third floor was divided into small rooms. It was to serve as the Yellow Springs Medical Department Headquarters, and as the principal hospital for the Valley Forge encampment. It was the first military hospital built in America. Even before construction was completed, the sick from Valley Forge were already being sent to Yellow Springs where Dr. Kennedy had been directing hospitals in three barns and the tavern. When the construction was completed, Dr. Bodo Otto was ordered to take charge of the Yellow Springs Hospital. Born in Germany, Dr. Otto had apprenticed at Hamburg and Harzburg, and became the surgeon in the Duke of Celle's Dragoons. In 1755 he arrived in America and practiced medicine in Philadelphia before moving to Reading in 1773. He served as a representative for Berks County at the Provincial Convention, and at age 65 assumed the duties of Surgeon of the Battalion of the Flying Camp Troop for Berks County. He felt he owed this debt to his adopted country for the opportunities, honors, and material things of life it had brought him. Later, Dr. Otto was ordered to Trenton, where he directed the first smallpox inoculation program for the army. In September 1777 he was sent to direct the hospital in Bethlehem, before becoming director of the Yellow Springs Hospital in early 1778. Assisting Dr. Otto, Dr. John Brown Cutting packed medicines at Yellow Springs. Frederick Wendt served as wardmaster, Catherine Wendt was the matron, and Alexander McCaraher was steward. The Rev. Dr. James Sproat was hospital chaplain for the Middle District, and visited the hospital every two weeks; he wrote in his journal that "a great deal of goodness of heart takes place here". Major Peter Hartman, a local German farmer, begged for food and clothing for the army from his neighbors, and transported it to Valley Forge, returning to Yellow Springs with the sick in his wagon. Dr. Otto's sons, Frederick, John, and Bodo Jr., also assisted their father, both at Trenton and at Yellow Springs. The graves of two nurses, Christina Hench and Abigail Hartman Rice, are located in the Pikeland Church cemetery on Clover Mill Road in West Pikeland Township, about a mile from the site of the Revolutionary War hospital. In fact, many local community members served the cause of independence here, though you will probably never read about them in our history books. We at Yellow Springs, however, feel proud of this local effort. Today descendants of these early patriots have come to Yellow Springs and the site of their ancestors' service. We are happy to count among our visitors the Dr. Bodo Otto Family Association, who held its reunion here last year. Members from throughout the country came to participate in the dedication of a plaque honoring Dr. Otto. The Pennsylvania Chapter Society of Cincinnati is also involved in the work at Yellow Sprinqs, and count among their ranks descendants of Dr. Kennedy, John Rose, and General Irvine. Others are descended from Christian Hench and Abigail Hartman Rice. These are just the names we know. I am sure there are many others yet to be traced. A Dr. Brown, who was transferred to Yellow Springs from Lititz, where he suffered through shortages of medicine, was the author of Pharmacopoeia, a 32-page book written in Latin describing various remedies that could be prepared from herbs and plants indigenous to the colonies. (It should be noted that the British had control of the seaports, and this prevented the receipt in the colonies of medicines from Europe.) Brown gleaned his information from the Indians who relied on such cures, as well as from Pennsylvania German healers and Quaker herbalists. It was the first book of this type in North America. The Yellow Springs Hospital administered to some 1300 ailing men, many suffering from typhus. Less than one out six died, which was a very good record. It is a generally accepted fact that the Yellow Springs hospital was clean and well-managed. General Washington visited it in May to bid farewell, and to issue orders regarding the remaining sick, before he left Valley Forge on June 19, 1778. Upon the closing of the hospital in 1781, the village once again became a spa, with three huge hotel facilities to serve guests who came to benefit their health in the three springs then in operation. This description of the Yellow Springs "rural retreat" appeared in the July 1810 issue of Port Folio: Were the efforts of Art combined with those of Nature, and regulated by the dictates of an improved taste, this highly favored place would burst upon the enraptured traveller with all the potent charm of magic or enchantment. Every charm with which Nature could embellish it is liberally bestowed. This singularly beautiful undulation of the grounds, exhibits a luxuriant variety of picturesque scenery, not to be surpassed either by the romantic wilds of Switzerland, or the enchanting vales of Italy or France. Some of the buildings of the era from 1820 on still remain, among them the Washington Building and the Lincoln Building, connected by a wooden piazza to the Inn and once known as the Cottage. The site changed hands numerous times during this period. New springs, in addition to the iron spring, were uncovered. A sulphur spring and a magnesium spring were discovered. Additional bath houses were erected to accommodate the growing numbers of visitors. Yellow Springs hosted such dignataries as Presidents Madison and Monroe, statesmen DeWitt Clinton, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster. Not only was the spa a site for rejuvenation of the health, it was also the center for popular entertainment. The popular songstress Jenny Lind came to the springs, and the sulphur spring has been dedicated to her name. Miss Lind was not the only popular entertainer from the era of the colorful showman P. T. Barnum to visit Yellow Springs, however: the world-famous Siamese twins, Chang and Eng, also performed at the Inn, much to the delight and fascination of the guests. In 1861 the Yellow Springs Hospital was reactivated as an army hospital, and used during the Civil War. Eight years later the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania acquired the property for use as an orphange for the children of casualties of the Civil War, and it became the Chester Springs Soldiers' Orphans School and Literary Institute. While photographs accompanying the annual reports of the Superintendent of the school tell a poignant story of small children attending school and church, performing farm and kitchen chores, and experiencing perhaps a touch of homesickness, there are also photographs that suggest a freer, brighter campus than those of some of the other schools. There are little girls in fairy costumes and geisha robes, dancing in the meadow; of boys in burlap sacks, playing games there. One is given the impression that the children at Yellow Springs enjoyed a happy experience, that there was a magic or romantic quality gleaned from the environment, with its springhouses and wooded paths. A pond was added, supplying ice and recreation; swimming, row boating, and ice skating provided amusement for the youngsters. Fire destroyed the Revolutionary War hospital in 1876, and damaged the Cottage in 1899. Both structures were rebuilt, but fire again claimed the hospital building in 1964, and only the field stone ruins remain. In 1916 the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts purchased the facilities asa residential summer school. In its 1919-20 Circular, it stated that the "chief objective of the Academy in establishing a summer school in the country is to supplement the work done during the winter at its school in Philadelphia, by instruction in painting in the OPEN AIR. ..."

The Summer School Catalogue for 1925 described the landscape: A dam provided a picturesque addition to the landscape. Bog gardens were created. (The gardens were referred to as "a studied thing, but studied to look natural".) Students said that the landscape was created with the artist in mind. A rustic informal elegance was the result. It was said that the Academy, in its summer campus, boasted an ideal companionship between man and nature seldom equalled elsewhere. And many of our country's most promising fine artists studied and taught at Yellow Springs, in the pastoral quiet of Chester County. The movie industry took over Yellow Springs in 1962 when Good News Productions purchased and moved into the buildings. Although the primary goal of the company was to produce religious films, two science-fiction classics came from the studios. Both the "4-D Man", with Robert Lansing and Patty Duke Astin, and the film that gave Steve McQueen his start, "The Blob", went from Yellow Springs to international acclaim as "sci-fi" favorites. But due to financial restraints at this time, the gardens deteriorated, the ponds washed out, and the trails became overgrown with brush. Among the projects of Historic Yellow Springs, Inc. is the complete restoration of the waterways, trails and plantings as they have existed over time. It is a massive undertaking and will continue over at least a five-year period, with work on the buildings going on at the same time. A complete study of the meadows is included in the project. I encourage each of you to journey out to our village, to see what has happened over the past fifteen years and share our vision of a completed restoration of Yellow Springs some day in the future.

The Jenny Lind Spring TopBibliography Bell, Whitfield J., jr. John Morgan: Continental Doctor Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1965 Ginger, Carl Revolutionary Doctor New York: W. W. Norton and Company, Inc., 1966 Claussen, W. Edmunds Revolutionary War Years Boyertown, Pa.: Gilbert Printing Co., 1973 Futhey, J. Smith and Gilbert Cope History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881 Gibson, James E. Dr. Bodo Otto and the Medical Background of the American Revolution Baltimore: Charles C. Thomas, 1937 Kessler, Charles H. Lancaster in the Revolution Lititz, Pa. : Sutter House, 1975 Martin, Joseph Plumb Private Yankee Doodle Ed. George Sheer Boston: Little Brown and Company, 1962 Torres-Reyes, Ricardo 1779-80 Encampment: A Study of Medical Service U. S. Department of the Interior, 1971 Weedon, General George Valley Forge Orderly Book Printed from original manuscript, Library of American Philosophical Society, 1777-78

Gazebo at the Iron Spring |