|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 30 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: April 1992 Volume 30 Number 2, Pages 41–52 "Under Whatever Name it May Go": The Vehicles on the Lancaster Turnpike On April 9, 1792 the Pennsylvania Legislature passed "An Act to Enable the Governor of this Commonwealth to incorporate a Company for Making anArtificial Road from the City of Philadelphia to the Borough of Lancaster", thus providing for the formation of The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company and the construction of the first major turnpike road in America. [*] To generate income and provide a return for the investors in the company, in Section XII of the Act, the company, "having perfected the said road",was authorized to appoint "toll gatherers" to collect tolls from all persons using the road and to stop "any sulky, chair, chaise, phaeton, cart, wagon, wain, sleigh, sled, or other carriages of burden or pleasure" forthe purpose of collecting the toll. The amount of toll to be collected "for every space of ten miles in length of the said road" was also set forth in this section of the Act. For carriages of pleasure, the toll "for every sulky, chair, or chaise, with one horse and two wheels, [was set at] one-eighth of a dollar; for every chariot, coach, stage wagon, phaeton, or chaise, with two horsesand four wheels, one-quarter of a dollar; for either of the last mentioned with four horses, three-eighths of a dollar; [and] for every other carriage of pleasure, under whatever name it may go, the like sums according to the number of wheels and horses drawing the same". The differences between these various types of carriages, so carefully delineated two hundred years ago, has become largely forgot since the coming of the automobile.

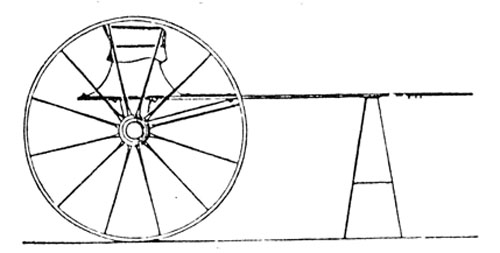

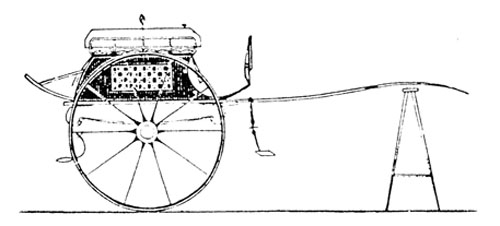

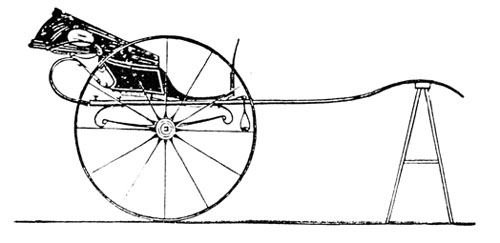

Sulky A sulky was a light-weight, two-wheeled carriage drawn by one horse, with a seat for only one person. Its name came from its accommodation for only one person. Its derivation is explained in a book on carriages and their historical associations compiled by Ezra M. Stratton and first published in 1878. "The name," he wrote, "is said to have originated thus: An English physician (Dr. Darwin) found that he lost much valuable time in allowing another to ride with him when on his professional visits, so he had a carriage built so narrow that it could not be expected to hold more than one person. His disappointed friends, deriving his purpose, derisively called his improved vehicle a 'sulky', by which name it has been handed down to our times." Because it was light in weight, and therefore easy on a horse, the sulky was particularly popular with tradesmen, doctors, and others whose work required considerable travel during the course of a day. The light weight of the sulky, coupled with its narrow seat for only the driver, also made it a popular vehicle for racing. By the middle of the 19th century, in fact, the name was applied primarily to the vehicle used in races, and over the years it was stripped down to the simple light-weight, streamlined sulky that is used in harness racing today. At the same time, a sulky used on the road and not for racing came to be known as a road-cart. The chair, pronounced "cheer", was also a light-weight vehicle with two wheels and drawn by one horse, but it had room for two passengers. It was basically a type of chaise, and the two names were often used interchangeably. Both names were derived from the French chaise, meaning a chair or seat, and the first chairs were probably simply a chair placed on a platform with wheels. The chair was usually, though not always, a carriage with no top, as opposed to a chaise, which had either a standing or folding top over the seat. Over the years, however, this distinction tended to disappear.

Chair In its earliest usage, a chair also generally had no springs, its body being set directly on the shafts, but by the late 18th century the body was often suspended on thoroughbraces, with wooden, or even steel, cantilever springs. (The chair shown above has both a top and springs.) It was a very popular vehicle, and in a number of notices of public sales for farms or plantations in the Great Valley in the first half of the 19th century a chair house was one of the outbuildings listed. from the Random House Dictionary

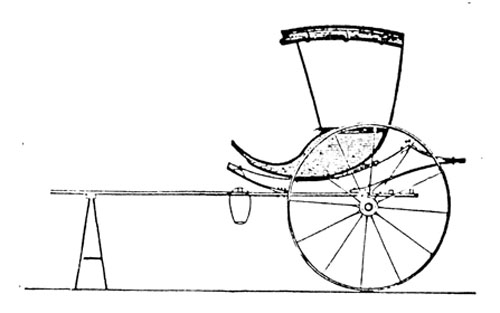

Chaise The chaise, generally pronounced, and sometimes colloquially written, "shay" (as in Oliver Wendell Holmes' well-known "The Deacon's Masterpiece, or the Wonderful 'One-Hoss Shay1"), was also a popular two-wheeled vehicle. The term, in fact, was frequently used generically to describe any light-weight two-wheeled carriage for two passengers, drawn by one horse. As described by Stratton, the body of a chaise was "hung upon springs made of wood generally, with rude bows or standing tops of round iron, hung around with painted cloth curtains. The linings and cushions [were] stuffed with 'swinging tow', sometimes salt hay". Don H. Berkebile, in his historical dictionary of carriage terminology, noted, "Some chaises had bodies set directly on the shafts, while others were mounted on leather thoroughbraces or a combination of steel and wooden springs with braces." We also have Dr. Holmes' description of the construction of the deacon's masterpiece, that "hahnsum kerridge" that after a century of service "went to pieces all at once": "... the strongest oak, That couldn't be split nor bent nor broke, -- That was for the spokes and floor and sills; He sent for lancewood to make the thills; The crossbars were ash, from the straightest trees, The panels of white-wood, that cuts like cheese, But lasts like iron for things like these; The hubs were logs from 'Settler's ellum1 Last of the timber, -- they couldn't sell 'em, ... Step and prop-iron, bolt and screw, Spring, tire, axle, and linch-pin too, Steel of the finest, bright and blue; Thoroughbrace bison-skin, thick and wide; Boot, top, dasher, from tough old hide Found in a pit where the tanner died. ..."

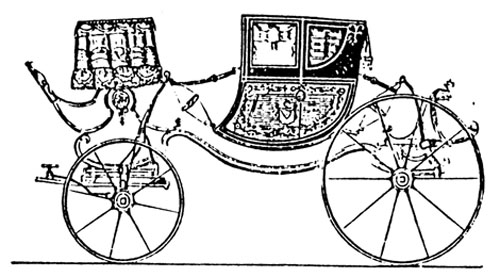

Chariot The term chariot today is generally associated with the chariots of ancient civilizations, the two-wheeled vehicle developed perhaps as early as about 2800 to 2700 B.C. in Mesopotamia and used in ancient Assyria, Egypt, Greece, and Rome. It is probably best remembered from the classic chariot race In Ber Hur. By the middle of the 17th century, however, the name was also used to describe a four-wheeled carriage designed to carry its passengers in style. Berkebile suggests that it was so named "because of the fashion of the time of assigning classic names to many things". He also described the chariot as "a sort of half-coach". It had a coach-like body that was enclosed and covered by a standing roof that was a part of the framing of the body, but the body was "cut off just in front of the doors, the front being closed by a panel below and glass above". Inside there was a single seat that held two or three passengers; in some there was also a folding seat in the front to accommodate children. The body was mounted on thoroughbraces and springs to provide greater comfort for the passengers. The driver's seat was located in front of the carriage, outside the body. Below the seat was a box, known as the boot, in which tools, luggage, and packages were carried. (The trunk of a car is still called the boot in England today.) The ownership of a carriage in the 18th century was often regarded as a sign of rank or wealth. They were frequently ornately decorated, with a handsome hammercloth over the driver's seat, and attended by footmen.

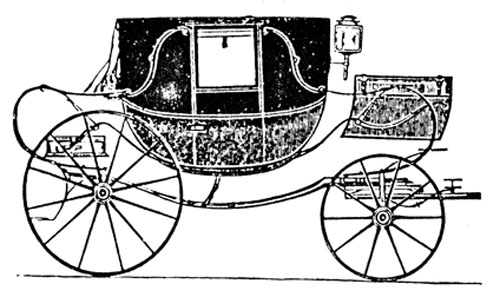

Coach A coach was a four-wheeled carriage somewhat heavier than a chariot. Its name, according to Berkebile, "is believed to have been derived from the Hungarian town of Kocs, where the earliest and most primitive form of coach is said to have originated", as early as in the 15th century. Its body was longer than that of a chariot, with the doors in the middle, rather than at the front, of the sides By the late 17th and early 18th century the coach body had also become rounded and shaped, and was decorated with handsome hand-painted door panels, some with carvings, and other ornamentation. The windows were made of glass. Inside, there were two traverse seats, facing each other, with room for four to six passengers. As with the chariot, the driver sat on a high bench or seat at the front, outside the body. The body was suspended from the running gear by leather thoroughbraces attached to springs. The front and rear sections of the running gear were also connected by two perches, rather than by one single heavier perch, in an effort, again, to make the ride more comfortable. A coach was usually drawn by a team of four horses, and hence the term "coach-and-four". Ownership of a coach was also a symbol of wealth and rank. In 1772 it was reported that there were only three coaches in all of the city of Philadelphia, one owned by William Allen, the chief justice, one by "the Widow Lawrence", and the other, by "the Widow Martin". (There were also only 18 chariots in the city at that time, "of which the proprietor, William Penn, and the lieutenant-governor, John Penn, had each one".) Twenty-two years later, in 1794, the year that the Turnpike opened, there were still only 33 coaches in Philadelphia, as recorded in the tax return for a "luxury tax" on all pleasure-carriages that the Congress had levied that year. (By contrast, in the 1794 return 520 chairs, including both chairs and chaises, and 33 sulkies were reported in the city.) Towards the end of the 18th century and into the 19th century the stage coach made its appearance, with companies organized to provide public transportation, carrying passengers for a fare. The stage coach was an improvement of the earlier stage wagon, described by Berkebile as "a primitive type of public traveling carriage". The two terms, stage coach and stage wagon, later became practically synonomous. They were called stage wagons or stage coaches because they made their trips in "stages", stopping every twenty miles or so to change horses. By 1823 there were at least eleven stage coach lines operating along the Lancaster Turnpike and stopping at the "Paoli", traveling between Philadelphia and Pittsburg, Harrisburg, York, Lancaster, or Baltimore, and, more locally, to West Chester and Downingtown. The fare was about six cents a mile, and the coaches traveled at speeds averaging about ten miles an hour.

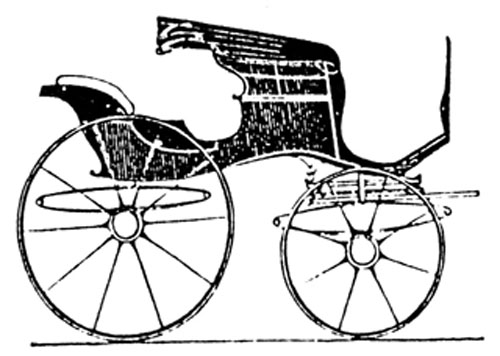

Phaeton A phaeton was a much more popular type of four-wheeled carriage, more informal and less ornate than either a coach or chariot, notwithstanding the classical implications of its name. Its name was derived from Phaethon in Greek mythology. (While driving the Chariot of the Sun, he lost control, and was in danger of setting the earth afire before Zeus struck him down with a thunderbolt.) Considerably smaller and lighter in weight, it could be drawn by one or two horses. Like a sulky or a chaise, it was also usually driven by its owner or a member of his family. There was usually a single seat, for two passengers, with a folding top over the seat, though some phaetons, sometimes referred to as a double phaeton, had two seats and room for four, or even six, passengers. On others there might be a small rumble seat at the back for the children, or perhaps a servant. The sides were usually open and without doors, and some models had a drop front to make them easier to get into and out of and to provide more leg room. A four-wheeled chaise was simply another name for a phaeton, reflecting its light-weight construction.

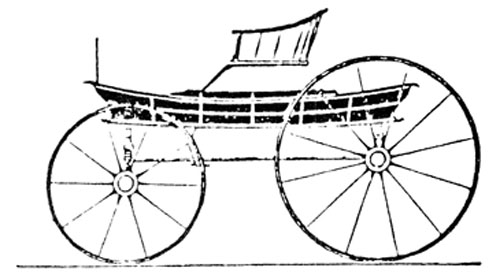

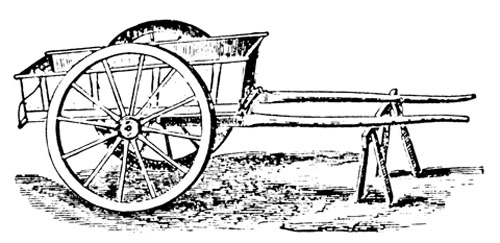

Dog Cart While most carts and wagons or wains were used as "carriages of burden", they were also sometimes adapted for use as pleasure vehicles. A cart, Berkebile observes, was a two-wheeled vehicle "that is made in numerous varieties, primarily as a freight carrier, though eventually many passenger-carrying carts evolved". Their use dates back to ancient times. A cart is actually simply a box on an axle, with no springs. Frequently the shafts were just a continuation of the lower part of the sides of the box or body. It was usually drawn by a single horse. In the 19th century carts were especially designed for use by children or as sporting vehicles. Their bodies were sometimes made of wicker, and the vehicle could be drawn by a small horse or by one or two ponies, in tandem, or sometimes even by a dog or goat.

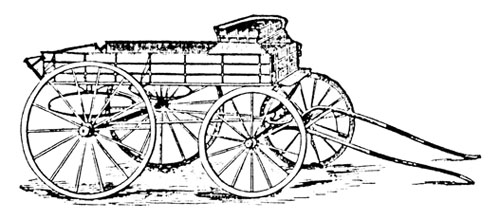

Country Pleasure Wagon A wagon, similarly, had a box body, originally placed directly on the running gear, with a seat across the front of the box or body. Its name is believed to have been derived from the Dutch or German wagen, originally used to describe any four-wheeled vehicle. The earliest wagons, again, were generally used to carry freight, but, like the cart, the wagon was later also developed into a passenger-carrying vehicle, as noted earlier in the stage wagon. By the early to mid-19th century a number of smaller, light-weight wagons were made to be used specifically to carry passengers. For the comfort of the passengers, these wagons were usually made with a frame of a springy type of wood, such as ash, or had elliptical springs under the body or under the seat or seats. A wagon with springs was sometimes differentiated from a regular wagon as a spring-wagon or platform-wagon.

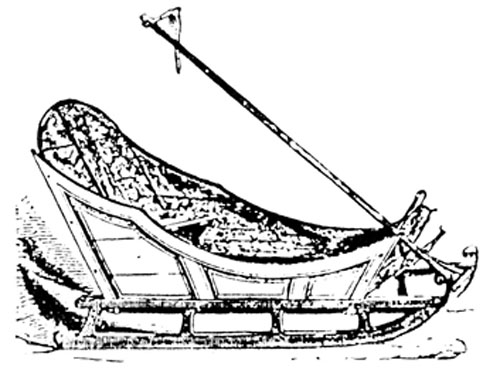

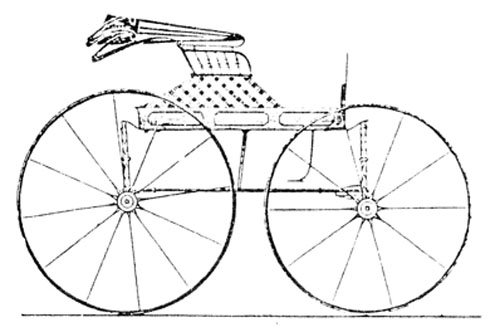

Early American Sleigh The sled or sleigh, of course, was used in the winter to travel through snow, with runners that slid over the ground rather than wheels. Both names are derived from the Middle English word sliden or the High German sliten, meaning to slide or to slip. The term sled was usually used to describe a vehicle used to carry goods or freight, while the name sleigh connoted a vehicle for carrying passengers. The provision in the Act that "the like sums" should be paid by "every other carriage of pleasure, under whatever name it may go" proved to be a wise precaution. During the 19th century a variety of names was used to describe the various types of passenger-carriages that used the Turnpike. A light sleigh, with a single seat that could hold up to three people, for example, was also popularly known as a cutter. It was a name that apparently originated at the beginning of the 19th century and was used into the 1900s. A sulky, similarly, was also sometimes called a solo, obviously from its accommodation for only one person. For the same reason, it was also sometimes referred to as a selfish: "American ladies," Stratton observed in 1878, "piqued at the exclusiveness with which men use it, have named it 'the selfish.'" A type of chaise popular in the 19th century was a gig.

Gig The name, the derivation of which is not known, was also apparently in use in the latter part of the 18th century; in his _A Treatise on_ Carriages, published in London in 1796, William Felton described gigs as "one-horse chaises, of various patterns". In general, a gig was, as Felton also noted, perhaps more "fancifully constructed" and more "fashionable" than a chaise, and also had a somewhat better suspension. During much of the 19th century, however, the term gig, Berkebile observes, was "almost synonomous with chaise". The chaise was also sometimes known as a whiskey, though a whiskey usually had no top over the seat. This name was also in use in the late 18th century, Felton noting that "whiskies are one-horse chaises of the lightest construction, with which the horses may travel with ease and expedition, and quickly pass other carriages on the road, for which reason they are called whiskies". (In other words, they could "whisk" right by the other vehicles.) During the latter part of the 18th century and first half of the 19th a type of chaise drawn by two horses was known as a curricule. It was a somewhat heavier carriage, and instead of a pair of shafts there was a single pole to which the horses were hitched. Because of this it was sometimes also known as a pole-chair. Some curricules were built so that the pole could be replaced by shafts for a single horse rig.

Square Buggy A type of phaeton quite popular in the 19th century was the buggy, a carriage that has survived into the 20th century, especially in the Amish community, and is also recalled in the phrase "Thanks for the buggy ride". Originally a buggy was a name for a sulky or a one-passenger phaeton, but in the 19th century the word was used almost exclusively as another name for a phaeton seating two passengers. By the early part of the 19th century, Berkebile notes, it was "the most popular carriage ever built, comparable to the famous Model T Ford of a later era". These are but a few of the many other names by which "carriages of pleasure" went during the 19th century. Other carriages took their names from the place where they were built, such as the Concord coach or Troy coach, the Rockaway, the Germantown wagon, which originated in 1815 in Germantown, or the Albany sleigh. Some were named for famous people, such as the Clarence, a type of coach named for the Duke of Clarence, or the Dearborn, a light-weight wagon so named because it was associated with General Henry Dearborn. Still others took their names from their designers, such as the Stanhope, a type of chaise designed by Fitzroy Stanhope in 1815, or the Brewster wagon, a type of buggy designed by a James Brewster in New York. But whatever their names, at the toll gates "the like sums" were paid. Since the tolls for "carriages of burden" were based simply on the width of the wheels of the vehicle and the number of horses pulling it (with a mule or a yoke of oxen the equivalent of a horse), the legislature was much less specific with regard to the nomenclature of the burden vehicles expected to make use of the new turnpike road. For such vehicles, reference was made only to stopping carts, wagons or wains, and sleds by the toll-gatherers to collect tolls.

Grocer's Cart The cart used to carry goods was also a two-wheeled vehicle, frequently without any springs. They were often identified by the products that they carried, such as a a hay-cart, a milk-cart, a butcher-cart, an ice-cart, a dump-cart, and so on.

Wagon The vehicles used the most to carry goods and freight along the Turnpike, of course, were the different types of wagon. They came in a variety of sizes, but were all basically vehicles with box-like bodies. As previously noted, on earlier wagons this body was placed directly on the running gear, with no springs or thoroughbraces to absorb the jolts, but later models were in many cases equipped with some sort of spring suspension.

Conestoga Wagon from Tunis Perhaps the best known wagon was the Conestoga wagon, with its six-horse team. It was originally built as a sturdy farm wagon, but was soon also used to haul freight between Philadelphia and the Conestoga Valley north of Lancaster and to other places. In the early 1820s, according to Julius Sasche, there was "on the entire length of the turnpike an almost unbroken procession of ponderous Conestoga wagons" transporting merchandise and produce to and from the interior of the state. A wain was another name for a wagon. The term was more commonly used in England than in America. The extensive traffic of both passengers and freight over the turnpike made it quite successful and, during its first four decades before the coming of the railroad, quite profitable. The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company in this period was able to pay liberal dividends to its investors, in 1827 as much as $72 a share, a 20% return. Along its length a number of inns and taverns were established to serve this traffic. Soon there were also blacksmiths, wheelwrights, and other businesses around these inns, and small villages began to grow. It was vehicles like these -- sulkies, chairs, and chaises; chariots and coaches; phaetons and sleighs and other "carriages of pleasure", under whatever name they went; and carts, wagons, wains, sleds, and other "carriages of burden" -- that made the turnpike the success it was, and an important part of the commercial development of not only the interior of the state and the west but also of our two townships. Its traffic was, as Sasche observed, "without parallel in the history of transportation in this country previous to the introduction of steam power". * See "The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company" [January 1985, Vol. XXII, No. 1] TopSources Don H. Berkebile Carriage Terminology, An Historical Dictionary Smithsonian Institution and Liberty Cap Books, 1978 Ezra M. Stratton The World on Wheels, or Carriages, with their Historical Associations from the Earliest to the Present Time [1878] Reprinted by Benjamin Blon, Inc. New York, 1972 Edwin Tunis Wheels: A Pictorial History The World Publishing Company New York, 1953 Bob Goshorn "The Philadelphia and Lancaster Turnpike Company" Quarterly, January 1985 [Vol. XXIII, No. 1] Leighton Haney Grace Winthrop "The Conestoga Wagon" Quarterly, April 1984 [Vol. XXII, No. 2] "The Stage Coach" Quarterly, July 1984 [Vol. XXII, No. 3] Grace Winthrop "The Stage Coach" Quarterly, July 1984 [Vol. XXII, No. 3] All illustrations from Stratton except where otherwise noted |