|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 30 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: April 1992 Volume 30 Number 2, Pages 53–62 Farms in the Great Valley and Southeastern Pennsylvania in the 18th Century The bounty of southeastern Pennsylvania was first described by William Penn in 1682 in a letter he wrote to The Society of Free Traders in London. "The country itself," he reported, "in its soyl, air, water, seasons and produce, both natural and artificial, is not to be despised." It was obviously a classic understatement. In a History of Pennsilvania, printed in 1698 by A. Baldwin, "at the Oxon Arms in Warwick Lane" in London, for example, Gabriel Thomas further observed that the soil was such that farmers "commonly will get twice the increase of corn [meaning grain in general] for every bushel they so[w] that the farmers in England can from the richest soil they have here". More recently, James Lemon, in his The Best Poor Man's Country, published in 1976, noted, "The soils of southeastern Pennsylvania were generally fertile, and [even] the poorer soils were good compared, say, with much of New England." In general, the climate and overall characteristics of the land were, in fact, quite similar to those of western Europe. As a result, the early settlers were able for the most part to adapt to the land quite readily. The land in the dolomitic limestone Great Valley was particularly fertile and, as Penn's new colony expanded westward, quite attractive. Its soil was rich and well watered by the Valley Creek and its tributaries and by many springs. And while the hills to the north and south of the Valley were wooded, the Valley itself was relatively without trees. The earliest settlers were Welsh farmers, many of them Quakers. As Lemon described them, they were "of a middling sort", neither wealthy nor particularly poor, from "the upwardly mobile part of the population". They were also, Stevenson Whitcomb Fletcher observed in his two-volume history of Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country Life, "thrifty, industrious, and God-fearing". The price for land in the colony, as set by the Provincial Land Office, was £5 for 100 acres. Each purchaser was also to pay an annual quit-rent of one shilling for each 100 acres, payable either in money or with wheat, flour, or other commodities. In 1732 the price was increased by William Penn's sons to £151/2 for 100 acres, with the annual quit-rent similarly raised to a half-penny an acre, but, as Sylvester K. Stevens pointed out in his Pennsylvania : Birthplace of a Nation, "by any standard the price was still a modest one". Most of the land was purchased in tracts of 100 to 500 acres. A number of the farms in the Great Valley in the early 18th century were about 300 acres in size, though some tracts were as large as 800 acres or more. When Lewis Walker, believed to have been the first settler in Tredyffrin, for example, left Radnor and came to the Great Valley he originally settled on a 300-acre property he had bought from David Powell, a land speculator and the deputy surveyor of the Welsh Tract, though he subsequently added to his property through additional purchases. Similarly, the farm of Rowland Richards in the Valley was also a 300-acre tract, also bought from Powell; that of Thomas Jerman had 300 acres, bought from William Powell, perhaps a brother of David Powell; that of John Wilson was also a 300-acre tract; and that of Llewellyn Davis another 300-acre parcel, which he bought from Lewis Walker. The largest properties in the Valley in the early part of the century were those of Lewis Walker, estimated to have contained perhaps 600 to 700 acres altogether, and the 800-acre property of John Havard. By the eve of the Revolution, however, both these "plantations" had been divided, by deed or inheritance, into smaller and separate farms for various members of their families. In fact, by 1760 the "typical" farm in Chester County contained about 125 to 145 acres, less than half the size of the typical farm at the beginning of the century. The homesteads of the early settlers, even with the smaller farms of the latter half of the century, were for the most part at some distance from each other. Although William Penn had envisaged the development of small agricultural villages, in fact each landholder tended to establish his homestead in the middle of his lands. A traveler in 1790, with perhaps some exaggeration, noted that between Philadelphia and Lancaster he found "not any two buildings standing together except at Downingtown". The homestead, or farmstead, included the farm house and the household garden, and generally occupied about three or four acres of the property. The household garden provided a wide variety of vegetables for the family's use. As early as in 1685 William Penn noted that at Pennsbury he had in his garden kidney beans and English pease "of several kinds", turnips, carrots, onions, leeks, radishes, and cabbage, as well as pumpkins, "mushmellons" [cantaloups], watermelons, squash, "coshows", buckhen, cucumbers, and "sinnels of diverse kinds". By the middle of the 18th century cauliflower, asparagus, parsnips, beets, parsley, peppers, and lettuce were also commonly found in the household vegetable plot. Fruits were not cultivated generally because many wild varieties could be readily found, among them, as Penn noted, plums, strawberries, huttle-berries [huckleberries?], cranberries, and grapes "of diverse sorts", and also blackberries, raspberries, and mulberries. On nearly every farm, however, there was an orchard, sometimes an acre or more in size. The trees were planted not so much for the fruit itself, but to produce fruit that could be made into cider or distilled into brandy. In fact, the fruit that was not converted to liquid form was usually used as feed for the livestock rather than for use at the table. While apple orchards were the most common, peach and cherry orchards were also frequent. An acre or two was also frequently set aside to grow flax, raised to make linen cloth or, with wool, into the traditional linsey-woolsey. An acre in flax could be made into enough cloth to clothe a family of seven. Occasionally there might also be a small flower garden around the homestead, and an herb garden to produce not only spices for the kitchen but also a resource for the family's pharmacopeia. Both livestock and grain were raised on the farm. "Farmers used their land," Lemon noted, "to produce a wide range of crops and livestock for home use and for sale. Plowland, meadow, gardens and orchards yielded crops, and pastures and fallow land provided forage for animals. Wood lots supplied wood for fuel and construction and were also used for grazing." As early as in 1708 it was observed that the inhabitants of the Welsh Tract had "many large plantations of Corn [grain] and breed an abundance of cattle, insomuch that they are looked upon to be in as thriving a condition as any in the Province". The production of grain, however, was the major thrust on most of these farms. Lemon has estimated that on a typical farm of 125 or 130 acres in the second half of the century about 26 or 28 acres were planted in grain, another 20 acres or so were set aside as pasture, and another 13 to 15 acres or so in meadowlands which were also used for pasture and for hay. As already noted, six to eight acres were planted in vegetables, flax, and orchards, with perhaps some tobacco. The remaining 55 or 60 acres were either lying fallow or in woodland. The number of acres planted and under cultivation was, of course limited to a large extent by the amount of time required to prepare, sow, cultivate, and harvest an acre of land and the manpower to do it. Some observers have commented on the rate at which the early settlers in Pennsylvania begat: it may have been, at least in part, that, as Stevens noted, "Large families were the rule because every child, male or female, added to the working force." The manner in which the soil was prepared for sowing grain is described in a letter written in 1754 by Lewis Evans to Thomas Powell in New York. "In general," he wrote, "the land is plowed thrice before it is sown; the first Time, about the latter End of April or the beginning of May; this is done in flatlands and 4 or 5 perches wide. It is a Rule to get this Plowing over before the Beginning of the Hay making. The second Ploughing the Farmers set about as soon as the Harvest is in, that is about the 20th or 21st of July N. S. and this is done on broad flat lands across the former Plowing; from whence it is called stirring or crossing. Before the end of August they sow the land with 3/4 of a Winchester bushel of Wheat to a Statute Acre, and plow it in Small Lands of 6 or 8 Farrows wide. In plowing they most commonly use two Horses, and them side by side; some have Oxen well enough trained for the Service; But in both cases the Plowman is [also] the Driver." The plows and other farm implements used by the colonial farmer were often heavy, cumbersome, and inefficient, either home-made or fashioned by the local blacksmith. The colonial plow was made almost entirely of wood, with a wooden beam, a wooden mould board (though in some cases the mould board was covered with a thin sheet of iron), and wooden coulders, with wooden handles. The harrow was also usually made of wood, with wooden pegs or teeth 10 to 14 inches long embedded about eight inches apart in a wooden triangular, or A-shaped, frame. Although it of course varied somewhat with differences in the soil and topography, on the first plowing, Evans indicated in his letter, an acre was "esteemed a middling Days work for one Pair of Horses", while in stirring an acre and a half or two acres could be plowed in a day "with the like Team". For much of the 18th century the plow and the harrow were the only farm implements for which horse power was used. In this area, and in southeastern Pennsylvania in general, horses were used more than oxen for plowing although the use of oxen was considered less expensive. For one thing, it cost less to buy a pair or yoke of oxen than to buy a horse, and thus did not require as large a capital investment. Oxen also required about half as much feed as horses, and did not need grain; they could work for longer periods of time with less rest than horses could; and when no longer serviceable as draft animals they could be fattened and then slaughtered for the table. After the soil was ready for planting, the grain, even corn, was usually broadcast by hand. The principal crop was wheat, which was sown in "immense quantities". The wheat crop not only provided food for the family, but was also an important cash crop, as there was a great demand for flour, bread, and other wheat products. A third to a half, or even more, of the total acreage planted in grain was seeded in wheat. Because repeated plantings of wheat (and other grains) deplete and impoverish the soil rapidly, the yield from an acre showed a marked decline in just a few years. On a newly cultivated field a yield of 20 bushels of wheat an acre could reasonably be expected, and in some cases yields of double that amount were reported. After a few years of successive plantings, however, the yield declined to half or less that from a new field. Although the concept of the rotation of crops was not generally recognized until almost the end of the century, the colonial farmer did realize the advantage of letting fields lie fallow every seventh year or oftener to maintain higher yields per acre. Another important grain crop were oats, grown primarily to provide feed for the horses but also used for oat flour and oatmeal. On the typical 125-acre farm four to six acres were planted in oats, with a yield of 15 to 20 bushels an acre, though again in a number of instances it was as high as double that. After the British occupation of the Great Valley in September 1777, prior to their capture of Philadelphia, the value of the oats lost to the British, according to the claims for damages filed after the war, was almost half that of the wheat plundered by the enemy. Rye was also an important grain crop. It was grown both to produce flour and for straw, used for making baskets and bee-hives, among other uses, as well as for tying corn fodder and for bedding. With wheat flour a valuable cash crop, on some farms rye flour and rye bread were used for everyday use in the household, with the wheat flour saved for special occasions. Sometimes wheat and rye were sown and reaped and ground together, with the flour produced known as meslin. Rye flour, combined with corn flour or meal, was similarly used in place of wheat flour and was known as rye-and-Injun. Parched rye was also used as a substitute for coffee, or coarsely ground and used as a cereal. The number of acres planted in rye was generally about a quarter of that planted in wheat, about two to three acres or so, with the yield from an acre somewhat higher than that from wheat. Another grain crop found on many farms was barley. It was grown primarily to make malt for brewing purposes, especially by farmers of German descent. On a typical farm perhaps about two acres were planted in barley, with perhaps another two acres in buckwheat. The yield in each case was about 15 bushels an acre. Just as home-made implements were used to prepare the soil, so were hand-made tools used to harvest the crop and thresh the grain. Grain crops in the 18th century, as they had been for centuries, werestill harvested with a sickle or with a reaping hook, raked into bundles, and tied by hand. (The sickle was somewhat smaller than the reaping hook and had a serrated or saw-tooth blade, the grain being pulled against the blade to cut it.) With a sickle a farmer could reap about an acre of wheat in a day.

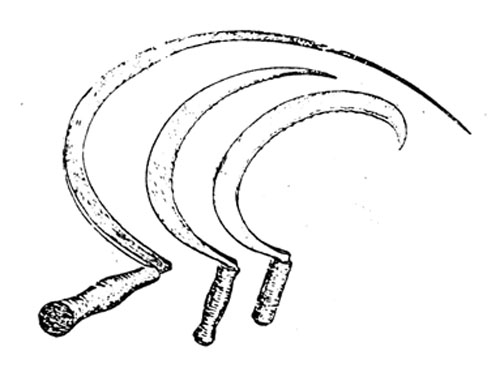

Reaping hook and sickles With the short harvest season, often neighbors helped each other, with "bees" to harvest and bundle the grain. It was not until after the Revolutionary War that the cradle, with which grain could be cut and gathered in the same operation, began to replace the reaping hook or sickle in harvesting; its use cut the time required to harvest an acre of wheat in half.)

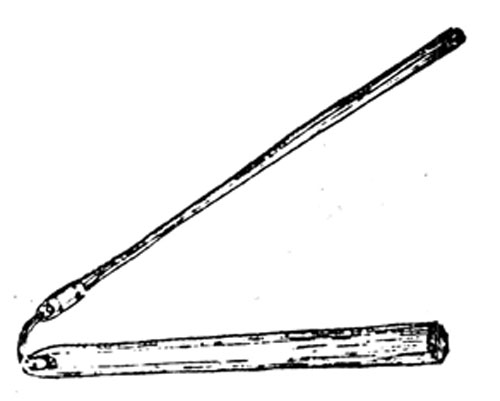

Flail Threshing was usually done manually with a flail. It too was a home-made tool, with a wooden staff, usually made of oak, to which was attached a break or souple, usually made of hickory, fastened with a leather strap. Sheaves or bundles of grain were spread on the barn floor or on a threshing floor and beaten or "thwacked" with the break to separate the grain from the chaff or straw. The threshers usually worked in pairs, and in a day they could produce about 20 bushels of wheat or 40 bushels of oats. Another method of threshing was treading. By this method the bundles of grain were placed on the threshing floor and horses or oxen were walked over them, round and round and round, to separate the grain. Although the production per man-hour of labor was about half again the amount produced by flailing, treading damaged the straw and was also considered "less sanitary", and was not generally used in this area. On the typical colonial farm there were also about eight acres planted in corn, with yields of about 15 bushels an acre. Because its cash value was only about a third of that of wheat it was not considered a cash crop; some of the corn grown was for family use as corn meal, in rye-and-Injun flour, or ground into middlings and used in making sausage or scrapple, but most of it was used as feed for the livestock. Root crops, such as potatoes, turnips, mangel wurtzels, and rutabagas, were also raised for fodder for the animals on the farm, with perhaps two or three acres set aside for these products. As noted earlier, horses were kept on most of the farms in this area, for farm work and transportation. In 1767, according to the tax assessment return for Tredyffrin for that year, six out of seven landowners had one or more horses. On more than a fifth of these farms there were four horses or more. Other livestock -- cattle, sheep, and swine -- were also found on many farms, raised to augment game as meat on the table and, in the case of sheep, to provide wool for clothing. LIVESTOCK ON FARMS Tredyffrin Township 1767

* Includes one farm for which number was not decipherable Source: Tredyffrin Tax Assessment : 1767 [Chester County Archives] In the early part of the century the livestock, to a large extent, was left to forage for itself in the uncultivated fields, meadows and swamps, and in the woodlands on the property and was not particularly well cared for or provided with shelter. By the latter part of the century, however, farmers began to build barns or other shelter for their stock and to give more attention to their care and feeding. It was also at about this time that granaries, corn cribs, and other outbuildings were erected "in significant numbers" to provide storage for crops; before that they too were generally left unprotected from the weather. The rapid adoption of this improvement is shown in the returns for the assessment for the federal direct tax, or "glass tax", in 1798. By the end of the century there were barns on about two-thirds of the farms in Tredyffrin township, almost half of them built of stone. Among the other outbuildings listed in the return, which was concerned only with buildings with windows, were spring houses, reported for more than a quarter of the properties, and outside kitchens, reported for a third of the properties. Also reported, in lesser numbers, were stables, milk houses, smoke houses, and wash stands. The most commonly raised livestock, other than horses, in terms of the number of farms on which they were found, were cattle. In the assessment return for Tredyffrin township in 1767 more than seven out of ten farms had some cattle, though not in great numbers. (Lemon has pointed out that the actual number of cattle was perhaps twice that reported as only the cattle three years of age or older were included in the tax assessment.) The cattle were generally of a mixed breed and, Fletcher described them, "small, scrawny and unproductive", kept "more for their meat and hides than for their scanty flow of milk". Cows, as distinct from cattle, were listed for eleven of the 81 farms in Tredyffrin in the 1767 assessment, but milk production of four quarts a day was described by Lemon as "very good", with the average nearer one quart a day. It was not until 1830 that dairying became a commercial enterprise. Pigs and swine, generally razor-backs, "long-bodied, long-legged, and long-snouted", were also found on many colonial farms, though specific information on their numbers is not available as they were not included in the tax assessments for Tredyffrin township. They were easy to care for, running wild in the woods and feeding on mast (acorns, beechnuts, and chestnuts) and roots most of the year. They also multiplied rapidly. In the fall, after the harvest, the hogs 18 months or two years old were caught and brought into pens to be fattened with corn, potatoes, apples, and other feed prior to slaughtering and butchering. At the time it was slaughtered a hog weighed about 200 pounds, and much of the meat was made into salt-pork, a farm-wife's stand-by. Some beef and pork were taken into Philadelphia for market and sale, and there was an export market for them as well. Sheep were also found on about half the farms, as reported in the 1767 tax assessment return, with a number of flocks of ten or twelve head. They were somewhat more difficult to raise than swine or cattle, and were raised primarily for their wool as mutton was held "in low esteem". (To encourage the production of wool for clothing, in 1701 the Provincial Council recommended that "every person throughout the Province and Territories who has 40 acres of clear land shall keep at least 10 sheep", but the recommendation was never officially adopted by the Assembly.) Other livestock frequently found on the 18th century farm included poultry of various kinds -- chickens, ducks, geese -- and swarms of bees. The 18th century farmer was not a particularly efficient farmer. With but a relatively few acres of his farm under active cultivation, as the soil in his fields became depleted or worn out from successive plantings he could simply clear out new fields for cultivation and, as noted earlier, let the older fields lie fallow for a year or two. It has been described as extensive, rather than intensive, farming. While the advantages of letting overworked fields lie fallow or "rest" for a year or two had long been known and were recognized by the colonial farmer, he had not yet discovered the concept of crop rotation or the value of planting the fallow field with a special crop to replenish the soil. As early as in 1740 it had been demonstrated that planting red clover improved the fertility of the soil, but the seed was still scarce and expensive and it was used on only a limited basis until after the Revolutionary War and the last decade of the century. Clover, incidentally, grew well in the limestone soil of the Great Valley. The rotation of crops began to gain acceptance at about the same time, to a large extent as a result of the efforts of Judge John Beale Bordley, regarded as "the father of crop rotation in America". He was an early advocate of rotating various grain crops, along with three crops of clover over an eight-year period, with the farm divided into a number of smaller fields to accommodate the rotation. (Some of Judge Bordley's experimental work, incidentally, was done on a 340-acre farm near Embreeville.) Nor were fields generally fertilized, again perhaps in part because of the ready availability of new, uncultivated fertile land. The use of manure was restricted by the relatively low ratio of livestock to the number of acres planted in crops. Under favorable conditions, in a year a head of cattle produces enough manure to dung a little over an acre, but, as previously noted, with the stock running loose for much of the year the conditions for the accumulation of manure were hardly favorable. What little manure it was possible to collect was frequently only enough for use on the household garden. Lime, of course, was available in large quantities in the Great Valley, and a lime kiln was not an uncommon adjunct to many of the farms in the Valley. In the 18th century, however, lime was used more for mortar in the construction of stone houses, barns, and other buildings than for fertilizing or improving the soil. One problem with its use was that most farmers did not know how to use it properly and effectively on their fields and in some cases even burned out their soil by using an excessive amount. As a result, there was some prejudice against its use and an acceptance of the old adage that lime made the farmer richer but his grandsons poor. With continued experiment and knowledge, however, its use increased in the latter part of the century, especially on the fields of clover, and by the early 1830s the liming of fields became "a standard farm practice". Notwithstanding this lack of efficiency, the colonial farmer in south-eastern Pennsylvania did quite well. Lemon has estimated that on a typical farm about 345 bushels of grain were produced: 80 bushels of wheat, 25 bushels of rye, 60 bushels of oats, 30 bushels each of buckwheat and barley, and 120 bushels of corn. Of this, about 295 bushels were usedfor home consumption: 50 bushels for household use by the family, 215 bushels as feed for the livestock, and 30 bushels for seed for the next year's crop. The remaining 50 bushels, mostly wheat, were surplus that was sold at market. Similarly, about 950 pounds of meat were produced, of which about a fifth -- 100 pounds of beef and 100 pounds of pork -- were surplus for market. In addition, some flax seed and hay, over and beyond the family's needs, were frequently available for sale, and perhaps some lumber and timber from the woodlands. In summary, Lemon concluded, "Early Pennsylvanians and their families, with few exceptions, ate heartily, were well clothed, and sold a surplus of goods. They were able to live comfortably even though they only scratched the soil and their system of farming was woefully inadequate in the eyes of reformers." He also noted, "The ... Quakers and Mennonites [who were predominant in the Great Valley] seemed more anxious to seek higher yields per acre by more astute practices" and that this "was reflected in their generally higher economic status". TopNote Much of the information in this article was taken from two sources: James T. Lemon's The Best Poor Man's Country, published by W. W. Norton [New York, 1976] and Stevenson Whitcomb Fletcher's Pennsylvania Agriculture and Country Life 1640-1840, published by the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission LHarrisburg, 1971]. Other sources included Sylvester K. Stevens' Pennsylvania : Birthplace of a Nation, published by Random House [New York, 1964], Bob Ward's article on "Some Early Landholders in Tredyffrin" in the July 1984 [Volume XXII, Number 1] issue of the Quarterly, tax assessment records for Tredyffrin township from the County Archives, and letters and other material from the files of the Chester County Historical Society. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||