|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 31 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: July 1993 Volume 31 Number 3, Pages 107–121 Club Members Remember Things We Used To Do By Hand

It was not so long ago, before electric washers and dryers and other household appliances, before furnaces were fueled automatically and the temperature was controlled by a thermostat, before calculators and electronic devices were commonplace, before agriculture was mechanized, that many chores were done manually. Here are the recollections of some of our club members of some cf the things we used to do by hand. TopThe Family Wash

I am amazed when I think of all the things we used to do by hand when we did the family laundry, washing clothes. One of my dreariest childhood memories is of a day when my mother and her sister took all of us "city cousins" out to the farm to do the wash. (My grandmother must have been sick that day, because usually on washdays we were encouraged to stay away from the farm!) In the farm kitchen the women soon had two huge copper kettles of water boiling on the wood stove. Batches of laundry took their turns at being boiled, and then were lifted out and put in galvanized tubs to be rinsed and wrung out with a hand- turned wringer. A wash board was used to get out the stubborn stains, with a great deal of scrubbing. We children were ordered away from the kitchen -- but we were expected to help hang the wash to dry. All day long the wash kept coming, to be put on sagging lines of rope propped up with clothes poles made from sapling trees.

Where there was a branch on the sapling it made a ready-to-use notch for the rope. (We were told not to play with the clothes poles, but they were too great a temptation.) In our home in town we had a Maytag with a wringer attached. It was in the basement, along with the furnace and the root cellar. With it was a double set of "sanitary wash tubs". (My mother was one of the first to have a pair of these tubs, and it was the latest thing in washing equipment.) The wash was agitated in the Maytag, and then was put through the hand-turned wringer into the first tub. From there it was lifted by hand into the second tub for a final rinse. Then the wringer was swung around by hand to the other side of the washer and the wash was again put through the rolling wringer and dropped into the clothes basket. In the winter it was then hung in the cellar to dry. During the rest of the year it was hung outdoors -- but often had to be re-hung in the basement or on the upstairs back porch to finish drying. (We lived in southern New York, and there was almost never a good washday; a washday when the whole wash was hung only once was most unusual. And, of course, by the time the last load was ready it might be close to noon, and many of the good drying hours had already gone by.) Diapers, incidentally, would dry outside in the summer sun in about only twenty minutes, but during the rest of the year they would often have to be hung on bars over the heat register to finish drying. When the electric dryer became available it was one of the greatest possessions of a young mother; armloads of warm, dry diapers came out, ready to fold, forty minutes after they were removed from the washer. Of course, today cloth diapers are themselves a novelty, with most young families relying on disposable diapers. Barbara Fry My mother also had a Maytag washing machine. Back then we would get up real early in the morning to do the wash, to take advantage of those morning drying hours and so we could do other things during the day. I remember getting up early and helping my mother do the wash when I was a little boy. I also remember a Maytag washing machine that was out on my grandmother's farm. That Maytag machine had a gasoline engine on it. (It sat in a shed at the back of the house, and it was a wonder that nobody ever was asphyxiated.) It had a flexible hose on it that you could take out the door to let the water drain outside the shed. It had a pedal on it, and you pushed down on the pedal to get the thing started: putt, putt, putt. Zeke Pyle I'd like to add one thing to that. When my mother hung the wash out in the winter, many many times the long underwear was stiff as a board! Marian Aument I had the same experience seeing my mother's wash out in the wintertime, frozen stiff. When I went to college and took physics I learned that when the long underwear went from frozen stiff to dry the drying process involved was what is known as sublimation. In sublimation a thing passes directly from the frozen or solid state to the vapor state without going through the liquid state. So we were all watching sublimation. Bill Denk Once the wash got dry we would bring in all the clothes and sprinkle them to be ironed. There were two or three flat irons sitting on the back of the stove, and a special handle fitted into them. We'd iron with one of them until it got cooled off. Then we'd put that one back on the stove to get hot again and take the handle out and put it into another one and keep on ironing. We always had to have a piece of wax or paraffin handy when we ironed. We used it to make the iron slide more easily over the clothes or whatever we were ironing. Mary Barbee

Top Starting the Car Turning the handle to roll clothes through a wringer reminds me of cranking a car by hand to start it, before the self-starter was perfected. When we first moved to Malvern, and my father commuted to Philadelphia from Paoli every day, we had just one car, so my mother would drive him to Paoli in the morning and pick him up in the evening. That didn't last very long, as they soon decided a second car would be a great convenience. So we bought a second-hand Model T Ford, but it really only partly solved the problem: instead of having to drive my father to the station in the morning she pushed him and the Ford toward Paoli with the other car until the motor in the Ford turned over. Remember when the station in Paoli was up on top of the hill? Well, my father always parked the car on top of the hill so that in the evening he could coast it down hill into gear to get it started to come home. That lasted about three or four weeks. We took the Model T over to West Chester (always parking it on the top of a hill or slope) and traded it in on an Essex. (We paid $75 for that Ford when we bought it, and traded it in for $100 on the new car; I thought my father ranked with Bernard Baruch as a financial genius -- a 33% return on his investment in just three or four weeks!) When the man delivered the Essex and came to pick up the Ford, he tried to start it and tried to start it, and it wouldn't start. He cranked it and he cranked it, and then suggested to my mother that she might want to go into the house so that he could talk to it in a language it could understand. After about 20 minutes he knocked on the door and announced that he'd have to call someone to come over and tow it to get it started. "I suppose your husband has the knack on how to start it," he observed. My mother agreed that he did. Bob Goshorn I remember, back in the little village where I grew up, there were some men sitting on a bench in front of the store, and a lady was out on the street trying to start her Ford. She was having an awful time crankinq it. Finally one guy (I had always thought he was a nice guy) said, "I can't stand it to see a woman work like that" -- and so he got up and walked into the store. Bill Denk TopCleaning the Gutter In front of our house in Grand Rapids, Michigan we had a wide sidewalk. Outside of the sidewalk was about a five-foot boulevard of grass and trees, with a walkway through it in front of each house so that people could get to the street and their carriages. (Our neighbor had a horse block at the end of her walkway to make it easier to step into the carriage.) Between the boulevard and the street was a cobblestone gutter. About two or three times a year it was my job to take a kitchen knife and a bucket and clean the weeds and grass from between the stones by hand because they must be neat and clean. It was not a fun job -- but we always had the second best looking gutter on the block. Now we have a paved street, but no cobblestone gutters to clean. Marian Aument TopAround the House and in the Kitchen This is an old butcher knife. Back about the turn of the century it was used for butchering pigs. My uncle's father and brothers used to do their own butchering -- by hand. I still use the knife occasionally, but not very often -- and not for butchering. I also have some old wooden-handled, hand-tooled forks. I have three of them, and they are the greatest thing for testing vegetables. A thing we don't use much any more is a metal reamer. We used it to make orange juice. They are all electric nowadays, but we used to make our orange juice by hand. Ginny Mentzer My mother's brother, Daniel Kline Savage, was born on a farm in East Coventry in 1879, but lived most of his adult life in Philadelphia. His vocation, described in 19th century terms, was that of an "artisan" --a machinist, blacksmith, or master mechanic. (He is listed in the Philadelphia city directory of 1925 as living at 2626 Cumberland Street, and his vocation is shown as a blacksmith.) Uncle Dan worked at the Budd Company for many years prior to the Depression-wracked 1930s, and later for J. G. Brill Company on Woodland Avenue. When there was no work to be found in the early 1930s, he and Aunt Lena (her real name was Selina) paid a visit of several years with us on my father's farm in Pottsgrove, while the economy was getting itself sorted out. Dan set up his blacksmith forge there and began making and repairing an endless succession of wrought iron things. He repaired barn door hinges, made new hardware for farm buildings, and repaired all kinds of kitchen utensils, pots and pans, all by hand. He also whittled stirring spoons, and paddles from fine cedar wood for kitchen use, especially useful when canning tomato preserves. Because he was quite deaf from a childhood illness, he did not communicate well and projected a very dour countenance to the casual observer. He delighted in frightening children, but under his bluff facade he had a very warm spot for youngsters, though he had none of his own. By hand he carved endless numbers of simple toys. His specialties were tops, carved from cast off wooden spools of sewing thread with a peg inserted in the middle, small baskets carved from peach pits, and an arrow that could be launched high into the air with a section cut from a discarded inner tube. For today's cynical generation they would barely rate a second look, but they were much sought after then. These simple toys, made by hand, had just as much play value and brought just as much excitement as most of today's electronic marvels. Herb Fry I have a thing made out of wood, about six inches long, shaped like an ice cream cone and painted on both sides. There is a hole running through it from side to side above the cone, and in the center of the dip of ice cream there is a round open space. Whether it was a toy or what it is I have no idea. (Someone suggested it might be a damper pull, but a damper pull would have a hook on it, and probably would not be made of wood.) Does anyone recall ever having seen anything like it or know what it was used for? Mary Barbee I almost brought an old electric razor with me. When I started shaving I of course used a hand razor, but as interns we worked around the clock. With no air conditioning in the summer time our faces would get pretty red, and using a hand razor could really burn. So one day we got hold of one of these electric razors. That's what started me off on that. Skip Eichner

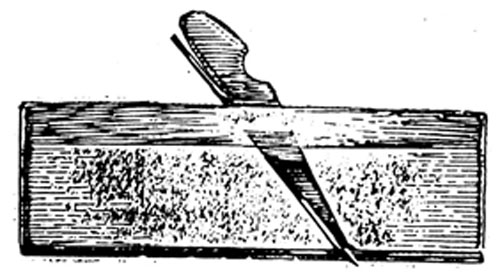

These are moulding planes that belonged to my grandfather. (One of the interesting things about one of them is that on it there is a mark that it was made in Philadelphia.) My father was a cabinet maker, and used these planes to make decorative moulding. They were used in the McCann house on Providence Road, just outside of Sugartown. He put in the library and den out there, using walnut and mahogany, and these planes were used in making some of the moulding. They are very sharp. The mouldings were all made by hand, but nowadays they don't even use moulding of this type. Evelyn Bloomer

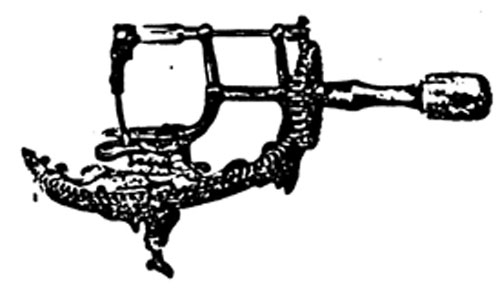

Here is an example of something that we now do by hand, but used to do with a tool. This is a button hook, and it was a very useful tool back in the Gay Nineties and early part of this century. Button hooks were most useful on shoes that had rows of buttons on them, the high-topped shoes known as "high-button" shoes. If you had a button hook, the job of buttoning them up was much easier. Mary Lamborn That reminds me that a couple of years ago we were guides at one of the homes on Chester County Day. Because of the arrangement of the rooms in the house, the visitors went down a short hallway to the living room and then doubled back part way to go upstairs. To explain this traffic pattern, I told them to go down the hall and then to "button hook" back to the stair case. The odd thing was that only a few of the women understood what I meant - but almost all the men did, from the button hook pass pattern in football. Bob Goshorn

I've also thought of something that's in reverse: an apple peeler. People today just take a knife and peel their apples by hand, but sitting on a shelf in our kitchen is an old apple peeler. There were, I understand, dozens, if not hundreds, of different types which were patented. It is cast iron. A handle turns two sets of right angle gears that, in turn, rotate a blade that peels the apple, which is held in place with three prongs. The whole assembly was clamped to a table when being used. In other models the apple is turned against a blade to take the peel off. I suppose that they were probably used when a number of apples were to be peeled at one time. Leighton Haney My mother's cousin married a girl, Mitzi, whose parents had run a hotel in Austria. She made all the great Viennese deserts in a way you will not find in a cookbook! It was the only time in my life that I've had real apple strudel. When Mitzi made strudel, her dough covered the whole table. She stretched it and pulled it out so that it was tissue-paper thin, and she never had any holes in it. When she was through she had a whole roll to give to each one in the family. I had a real mob of cousins, and we would always go to where the action was. That frequently was the kitchen, and it is interesting to think back to how many interesting things we watched there. Of course, much of our food came from the family farm. All our chickens were raised and killed on the farm, and plucking the feathers was a chore. Chickens sold at the market, of course, had their feathers removed, but how well this was done determined how much time the housewife had to spend singeing the bird and plucking its pin feathers. Even the store-bought birds always had a few remaining to be plucked by hand. In the early fall the food from the harvest was canned and put up for the rest of the year. Baskets of peaches, pears, tomatoes, string beans, corn, and the like were processed and put into jars, to be kept in the fruit cellar to feed the family for the year. After World War II home freezing replaced much of the canning, and today fresh produce can be bought the year round. Barbara Fry TopPrinting Presses and Ice Cream My father was a job printer, and when I was in grade school I'd come home and have to help my mother in the store or my father in the print shop. He had an old Oliver printing press, and when I saw him come in with a big stack of paper and put it on the shelf along side of the press I knew that on that day I would be helping him. You had to pump the press with your foot, and that would make the ink rollers go around and at the same time bring a plate back for the paper. Then you put one piece of paper on the plate, and it would go forward -- keep pumping -- to be printed. Then it would come back again, and you'd have to take the printed sheet out with your left hand and put in a new sheet with your right. And this went on and on and on -- it was the most boring work. I'll never forget it. Of course, today the paper is fed into a press mechanically, and you don't have to do it by hand anymore. I enjoyed working in the store much more -- but when I dished out the ice cream my mother was always afraid that I'd give away all the profits! Anne Slaymaker

Home-made ice cream was always a special treat three or four times each summer. It wasn't made in ten or fifteen minutes; it took much closer to an hour to make it. Weeded to start were a churn (a wooden type bucket, with a metal gallon insert with rotating blades), a large container of milk, vanilla or chocolate flavoring, and salt and ice to be compacted in the space between the bucket and the insert. Now you needed muscle! You had to crank and crank to keep the blades turning until the mixture in the insert somehow turned into the almost solid form of home-made ice cream. The special reward for me was afterwards, when I could scrape all the blades. Oh boy! Clyde Mentzer TopKeeping the House Warm A chore to be done each fall by hand was to start the fire in the furnace for the winter. I won't try to describe its various problems because Robert Benchley has already described them so well in his "Thoughts on Starting up the Furnace" in his book Pluck and Luck. "Building a furnace-fire for the first time of the season is a ritual which demands considerable prayer and fasting in preparation," he observed, adding that "At times like these a man should be alone with his own soul" as he gets the kindling, together with a quantity of crumpled newspaper, ready. After they are blazing, "the real test of the fire-builder" comes as the coal is added. After several unsuccessful efforts at this, the last step, he finally noted, is "to go upstairs and telephone for Jimmie ... who makes a business of starting furnace-fires", a step which requires "no more practice than knowing how to use the telephone" and is "the only way of getting your furnace going". Nancy Pusey Our problem was not so much getting the fire started as keeping it going. Our furnace had a really good draft. The only way I could keep it going overnight was to set the alarm clock for about three o'clock in the morning and get up and go down to the cellar and throw in another couple of shovels of coal to hold it until morning. During the day my wife similarly had to schedule all her activities in the winter so that she could be home when it was time to stoke the fire -- again! (What's worse, the house was really never that warm, in spite of our efforts.) It was an arrangement that lasted only one winter. By the next year we had converted that coal-eating monster into an oil burner. The coal bin, about 8' by 10', is still there in the cellar, but now it has storage shelves, rather than coal, in it. Bob Goshorn We didn't have a central heating system; our ten room house was heated by a small two-burner coal stove in the kitchen, an excellent fireplace in the front living room, and a coal stove in the middle room.

In late October each year it was time to put up the coal stove. My mother and father would take all the pieces out of the cellar to the back yard. Each piece had to be cleaned, and the black ones were then polished with stove black. The first thing put down was the zinc plate on which the stove was to be placed. It was wery important to get this in exactly the right place. Then came the shiny base of the stove. After that each cast iron piece was carefully put on, the whole thing finally topped by the shiny ornate cap section. The bolts were then dropped into the hinges on the door. This was the time when the children could help by checking the isinglass windows in the doors. They broke easily, and so they had to be cleaned very carefully or, if they were broken, replaced. They were made of layers of mica, and I always loved the feel of them. Sometimes the whole pane had to be replaced; sometimes just a layer of mica was taken off. The last thing to be attached was the chimney. After Dad had put the lower sections together the decorated tin plate in the ceiling was removed, and Mother would stand upstairs in the bed room above and help keep the chimney straight. When everything downstairs was all right, Dad would take the remaining parts upstairs and add a couple more sections on the chimney. After removing the tin plate from the wall in the bed room he would then put an elbow piece on the chimney, and somehow it was finally connected with the smoke stack that went through the roof. It was a real joy to see the fire through the isinglass windows on the doors of that pot-bellied stove. Marian Aument I come from the state of North Dakota, where I grew up as a boy, and it gets cold there! I was in Bismark the year that it got down to -54° -- 54 degrees below zero -- and that's mighty cold. Nowadays you keep the house warm simply by setting and adjusting the thermostat, and it's very simple, but it wasn't always that easy. Of course, you're all familiar with stoking a furnace by hand, and we did that too. But there was an unusual variation of that in a little town to the west of Mandan and Bismark. It seems that North Dakota is largely underlain with veins of lignite, and after one farmer had built his home he found that it was on one of these lignite veins. His basement was entirely lignite. So when winter came and he needed coal for his furnace, he simply enlarged his basement! Our family lived in an old frame house in the village of Forman in Sargent County in the years immediately following the First World War. I still recall the preparations we made to get it ready for the expected cold weather -- and also the doubts expressed by my mother about the specifics of those preparations. My father was the town druggist. Early in the fall he made arrangements with a local farmer to improve the insulation of the house. The first step in this process was taken by a local handyman, known familiarly as "Rattlesnake Pete". He was really a nice chap, as I recall him. His task was to apply one width of tar paper -- it came in 36-inch rolls, I believe -- around the perimeter of the house, at ground level. The tar paper was held in place by means of wood slats, nailed to the wood clapboard siding of the house. Then Father engaged a nearby farmer to bring in one or more loads of "barnyard mixture" and to apply it to the foundations of the house, sloping it at a 45° angle from ground level to the top of the 36-inch protective covering of tar paper. For the uninitiated -- those who have never lived on or near a farm -- the barnyard product was a mixture of bedding straw and animal manures that was removed periodically by farm hands from the stalls or stables. (I am sure my mother knew this, but to her that stuff around the house that winter was just "manure", and she was clearly offended.) Yet I assume it did what was expected of it: its mere presence kept the cold winds of winter off the house's foundations, but more than that, the chemical action, as the various components interacted, produced significant heat of its own. I do not recall that this procedure was followed in subsequent years, but it was quite common in that little town in southeastern North Dakota. And as I think of it now, it was a somewhat astonishing, but surely effective, early example of "recycling": in the spring, before rising temperatures made the material objectionable, the same farmer would remove it, taking it to his farm and fields, where it served as a well rotted, organic top dressing, thus serving to fertilize his new crops. Bill Denk Another thing we did by hand was saw and cut fireplace wood. I still have one of the saws we used. It had a small handle, which is now lost, that could be attached to either end to make it either a one-man saw or a two-man saw. (The trick when you were using it as a two-man saw was to pull but not push as the saw went back and forth through the log.) Our next door neighbor was Syd Morris; he was a Sharp through his mother's side of the family, and he considered it his responsibility to take care of Sharp's Woods, over on the west side of Leopard Road just south of Sugartown Road. Just about every Saturday morning in the late fall and winter he would round up me and our other two neighbors, Bill Brosius and Jack Croasdale, and take us over to the woods to clear out the dead trees and cut firewood. The first step was to fell a dead or dying tree, maybe as big as two feet in diameter or more. Jack Croasdale had had some training in forestry, and he would put a handkerchief on the ground where he had determined that the tree would fall. With axes, wedges, and a two-man saw we'd bring it to earth. If it fell on the handkerchief, we'd hear about it for weeks; if it didn't, he was reminded equally often of that fact. Syd Morris also provided the tools, and the wedges for splitting the log-length sections we cut were really excellent. (He had them especially made at the Wheeler-Morris Steel Works, of which he was one of the Morrisses.) But despite the quality of the wedges, there were from time to time large logs with knots or other irregularities that made them simply impossible to split. They were not just left there, though. After a couple of hours in the woods we'd load up a truck and deliver the wood. If anyone had missed that day, along with his share of the firewood would be a couple of the "unsplittables". They sure were durable; I still have a couple of them, out behind the garage, that haven't rotted away yet. Later Syd got us a couple of sons-in-law and a chain saw to help with the project, but for years we did it all by hand. Bob Goshorn I have one of those two-man hand saws at home too, but it can be used only as a two-man saw. It's a thing called a "shadback", straight on the bottom but bellied on the back end. Zeke Pyle

Top On the Farm I bought this old butter churn about a year ago. (My daughter's last words as I took it out of the house with me were, "Don't break it!) Do any of you remember churning your own butter? Skip Eichner When we were on the farm I used to churn butter, and we used to get lots of buttermilk. Folks from the south, of course, think biscuits are much better if they are made with buttermilk. To make butter you first put sour milk in the churn. Then you churn and churn until yellow specks of butter start to appear. When the butter appears, you gather it with a wooden churner. Then you take it out and put it in a dishpan and wash it two or three times with cold water. You then pour the water off and add a salt mix. After the butter is washed several times and the salt added you take it out and put it into a butter mould or print. Then it is taken out and wrapped in wax paper, to be stacked up in the freezer. You can keep it for a good while. I don't have my butter churn anymore, but it was similar to this one. Mary Barbee

Having grown up on a farm, I think more things were done by hand on a farm than in any other place. Technology as applied to agriculture did not come along until after the 1930s. Today we have combines to cut wheat and thresh it in the field. We have equipment that harvests the corn and cuts it up into ensilage, ready to be put in the silo, right in the field. That was all done by hand in former days. In the old days the making of hay, for example, was a much more lengthy and leisurely-paced activity than it is today. It started with hitching a team of horses to a mowing machine to cut the standing grass. After the sun dried the grass, a single horse dump rake would collect the hay into what were called "windrows" across the field. (If the hay was especially thick, a horse-drawn tedder would first scatter the hay to facilitate drying.) Then, on a bright sunny day in June when the hay was ready, it was time to hitch the team to the hay wagon and proceed to the field to gather it. Two men with pitch forks rolled the hay into piles in the field. Usually it was the job of the youngest member of the crew to drive the team and position the wagon as the hay was then lifted onto it from below. When the load reached a height beyond the reach of the men on the ground, the hay wagon would be driven to the barn floor. Unloading the wagon was done by means of an ingeneous device called a hay hook, or hay fork, which was installed on a track along the ridge pole of the barn. The hay hook was lowered to the wagon, inserted into the hay, and a lever set to keep the hay from sliding off. A heavy rope attached to the hook ran through a series of pulleys to raise the load of hay to the top of the barn, with a single horse hitched to the other end to pull the hay up to the track at the roof. From there it rolled to the adjacent hay mow. A yank on a smaller control rope dropped the hay into the mow, where a man with a pitchfork leveled it across the mow. Keeping the hayseed out of your hair was always a chore, and when the mow became nearly full avoiding bumping your head on the roof was a skill to be cultivated. Haying in those days, like most work on the farm, was largely done by hand. But it had its compensations: it was always done on delightfully fair early summer days, with lots of fresh home-made lemonade available to quench your thirst. What more could you ask? Herb Fry How about getting up at four o'clock in the morning to milk the cows by hand? Now it's done with milking machines, of course. Leighton Haney TopDigging Graves There was a picture in the newspaper recently of a grave digger working in a cemetery in Pennsylvania. According to the account in the paper, it was taken at the only cemetery in the state that still uses grave diggers to dig out the grave by hand. That was always one of the many tasks the church sexton performed. Clyde Mentzer TopBefore Electronics I'm old enough to remember when you had to tune your television set by hand! Now it's all done with push buttons on a remote control unit. Leighton Haney I remember with great pleasure a wind-up phonograph I used to have. It was given to me by my father on my graduation from high school and, back before transistors and small batteries, had the added advantage being able to provide music on dates at places without electrical connections. It played the old 78 r.p.m. records, of course. Elizabeth Goshorn My daughter recently reminded me of the time, before hand calculators and electronic scanners, when we used to do arithmetic "by hand". You would walk into a grocery store, for example, and after the clerk had got the various things you wanted from the shelf he'd take a paper bag and write the numbers down: eggs, $.13 a dozen; bread, $.08 a loaf; bacon, $.27 a pound; oranges, $.29 a dozen; coffee, $.21 a pound; round steak, $.36 a pound. Then he would add up each column of figures, from right to left, and put down the total -- $1.34 altogether. You could check the total by adding up the figures yourself as he did it, and the record was right there on your bag. Bob Goshorn

Top Hauling Water It's hard for my wife to believe, but the little village I came from had no water system. Our house had a cistern that collected rain water from the roof, and that was considered adequate for washing clothes and that sort of thing, and for washing your hands and bathing. But for drinking purposes I had to take my little four-wheeled coaster wagon down to the village well and wait until the water dribbled slowly into a pail. I'd bring back two or three bucketsful at a time. And that was our water system -- a cistern and the village well. (It seems impossible, when I look back at it, what a miserable place it was!) Years ago, when I last worked for Ford, I was lucky enough to be in the echelon of people who could lease a car, and I leased a Lincoln. At about that time we decided to go out to North Dakota to show our kids where I came from. And I was a little embarrassed., because I thought, "My golly, here I am, going back to my little home town, driving a Lincoln!" Meanwhile, North Dakota had come out of the Great Depression and had struck oil -- literally -- in the northern part of the state. When I got there I found that my friends were doing very well; they were driving Lincolns and Cadillacs, and some of them even had their own airplanes. Times have changed! Bill Denk |