|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 36 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: October 1998 Volume 36 Number 4, Pages 105–112 The General's Marquee and Dr. Burk The author would like to acknowledge that he is not an historian, but hopefully he is a reasonable story teller. The saga of the marquee (camp tent) used by General Washington at Valley Forge in 1777-1778 has been well documented by more qualified writers. At present there is no question that Dr. Burk did purchase a marquee from Mary Custis Lee. But historians also agree that the purchased marquee now exhibited at Valley Forge National Historical Park may only be similar in appearance to other army marquees that were made for use during the Revolutionary campaigns, and may not be the marquee actually used by Washington at Valley Forge. The question still remains to be answered, "Did Dr. Burk know that the tent he purchased and received in 1909 was not used at Valley Forge by Washington?" If that be the case, perhaps that is the real story of the General's marquee. This particular chronicle of the field camping tents, referred to as marquees, and used by General George Washington during the Revolutionary war and most specifically during the 1777-1778 encampment at Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, begins with the story of the Reverend W. Herbert Burk. On Washington's birthday in 1903, Dr. Burk delivered a discourse on Washington the Churchman at the All Saints Church in Norristown. "Would that we might," he observed, "rear a wayside chapel, a fit memorial of the Church's most honored son ...." With these words, the building of Washington Memorial Chapel in Valley Forge State Park would soon be underway with Dr. Burk destined to be appointed the Chapel's first rector. The artifact collections of the Valley Forge Historical Society were initially started by the Reverend Burk in early 1908, while the Society itself was not founded until later in 1918. Dr. Burk was a passionate collector of hundreds of artifacts related to the struggle of the soldiers across the fields of Valley Forge. In the third edition of Burk's Guide to Valley Forge, published by the Times Publishing Company in 1912, he writes: "By far the greatest relic of Washington at Valley Forge is the marquee, or office and sleeping tent, in which he spent his first week upon the hills." At this point in time, the real story of the marquee begins. In an article appearing in Valley Forge Briefs, published in 1987, Paulette Mark writes that during the Spring of 1776 an order was placed with Plunkett Fleeson, a merchant located on Third Street in Philadelphia, for three tents and tent equipage. The tents were to be made under the direction of Captain Moulder of the artillery, and were to be delivered to General Washington. The Sleeping tent --was rectangular in shape with an A-frame roof extended at each end and by semicircles, having a roof of a semiconical shape. It was 16' long by 10' wide. The inner chamber had a wooden floor and was rectangular, with a smaller rectangular section at one end that housed the General's cot or his four-poster bed. Washington also had this sleeping tent modified by adding a second entrance on the side opposite the original entrance. The Dining tent -was the largest of the tents ordered, measuring 18' by 20'. This tent was sometimes referred to as a banquet tent since it could hold forty to fifty men under its roof. The Baggage tent- was the third tent listed on the original order placed by Washington, but it seems to have disappeared, leaving historians baffled as to its whereabouts and questioning whether it was ever completed and delivered. The marquees were made of heavy linen, all hand sewn in Fleeson's shop, and they had an inner lining to further protect the General from the elements. Washington also purchased eighteen camp stools from Fleeson, along with camp tables, a good camp bed, dish ware, pots, cutlery and other items that were all transported by the army baggage wagons. The Picket Post, published by the Valley Forge Historical Society, states that the Sleeping tent, even when Washington stayed in a private dwelling, would be set up in the yard or nearby the dwelling. "Washington was in the habit of seeking privacy and seclusion, where he wrote memorable dispatches. He would remain in the retirement of the sleeping tent sometimes for hours, giving orders to the officer of his guard that he should not be disturbed, save on the arrival of an important express." When Washington first arrived at Valley Forge, the marquee was set up on a hillside in close proximity to the artillery park established by General Knox. Initially it was the General's intention to make his permanent Headquarters with the field soldiers, as he actually did for a few days until Christmas day in 1777. In An Account of the Valley Forge Encampment, Barbara Pollarine writes that Washington soon moved into the Isaac Potts house, located near the confluence of Valley Creek and the Schuylkill River. He rented the house from its occupant, Mrs. Deborah Hewes, who vacated the dwelling and moved nearby with relatives, By renting the house, Washington thereby obeyed his own orders not to take advantage of the local civilians. He and his aides moved into the five-room house; which served as an office and home for him and his wife, who arrived several weeks later, for his staff, and for a constant parade of visitors. It should be noted that there is no record of any of the marquees being set up near the Potts house while the General was in residence. At the end of the Revolutionary War, following the surrender of British troops at Yorktown, Washington returned to Mount Vernon with some of his personal field equipment being put in storage, including the marquees, in the garret or attic of his home. Upon the death of the General in 1799, many of these personal articles were dispersed through his Will, with many additional items sold by his heirs through public auction. The marquees and other items were inherited by George Washington Parke Custis, Washington's adopted son (Martha Washington's grandson), who moved the tents from Mount Vernon to his newly built home in Virginia. Mark writes that Custis built a large Greek style house on a knoll on the Virginia side of the Potomac River across from Washington, DC that he named Arlington House. Custis was very proud of his adopted father, and his father's personal items that he had collected through inheritance. During Custis's life time, the marquees would be displayed at special times when he would have them erected on the lawn for garden parties and other special events. Custis even used the marquees occasionally to provide shade when his sheep were being sheared. Prior to his death in 1844, Custis gave the Dining Tent to the Federal government.It was placed on display at the Federal Patent Office, since the country as yet did not have a national museum during that time. At Mr. Custis's death, Mrs. Mary Custis Lee, his daughter and the wife of the future Confederate general, inherited the remaining marquee, equipage and Washington's personal items from her father's collection. At this point in the story, fate, in the form of the Civil war, stepped in to interrupt the trail that would eventually bring the General's marquee to Dr. Burk. With the outbreak of the war Mary Custis's husband, Robert E. Lee, resigned his commission in the Union army and took command of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia. With this decision by Lee, the Federal government reacted when Secretary of War Stanton ordered troops to seize Arlington House, and return all the belongings of Washington back to the Capital. The Sleeping Tent and other items were sent to join the Dining Tent at the Patent Office. After the war, Mrs. Mary Custis Lee petitioned President Andrew Johnson and the Federal government for the return of the marquees and other Washington "relics" that had been seized. Unfortunately, many politicians on both sides of the aisle stalled, and prevented the items from being returned to their rightful owner at that time. In 1883 the first National Museum was opened, and the marquees were moved from the Patent Office to be displayed at the grand opening celebration. The Lee family continued to press their claim over the years for the return of the items, and finally during President William McKinley's term of office, the transfer was completed. And it was on May 27, 1907 that the Reverend Burk secured an option from Mary Custis Lee, the daughter of Mrs. Robert E. Lee, for the purchase of the marquee for $5000. On August 19, 1909, Dr. Burk made the first payment of $500 from funds contributed by friends of Washington Memorial Chapel, and received the tent - minus one-half of the side wall, and an inner lining - from the National Museum. The following day, 131 years after it was supposedly carried from Valley Forge, the marquee that Dr. Burk presumed was the original used at Valley Forge was set up in a small room at the Chape! that Burk named the Museum of American History, At this point in the trail of the marquee, perhaps a simple question needs to be addressed: Did Dr. W. Herbert Burk buy and receive the "actual" or original sleeping marquee used by General Washington during the army's encampment at Valley Forge in 1777-1778 ? If Dr. Burk did not purchase and receive the original marquee used at Valley Forge, where is the missing marquee of the General, and why would Dr. Burk buy this marquee ? As the reader will soon understand, the answers to these questions are totally speculative, and can not be confirmed by any historical evidence. Did Dr. Burk buy and receive the marquee used by Washington at Valley Forge ? While Washington passed the winter months in the Potts house, it is documented in several references that some of the marquees, and these are not identified, were sent to be repaired in preparation for their use in future campaigns. At this particular time in December of 1777, the marquees that were ordered in the Spring of 1776 and billed May 4, 1776 by Fleeson to Washington, based on Washington's expense report, had been delivered to the General on May 11,1776. Mark also writes that an exchange of letters with the Quartermaster Officer in 1777 indicates that a set of tents were shipped off for repairs, and the repairs were made while General Washington resided at the Potts house.Is this in reference to the Fleeson marquees, or to a set of older tents used by Washington prior to 1776 ? The correspondence also records that the red worsted trim on the Dining Tent canopy was replaced just in time for the 1 778 campaign season. So now we come to the first of many contradictions. In The Washington Chapel Chronicle dated September 15, 1909, an article states that the "marquees were first pitched on the heights of Dorchester [outside Boston] in August of 1775." Dr. Burk also makes this same statement in his 1912 Guide to Valley Forge publication. It should be noted that Dr. Burk writes, in his Making A Museum - The Confessions of a Curator: "nor [did I] tell how I identified the marquee without any shadow of a doubt." This account by Dr. Burk and the Historical Society is in direct conflict with the Mark article stating that three marques were ordered in the Spring of 1776. Both articles provide identical references to Mr. Plunkett Fleeson being the maker of the tents. In addition, references to the tents having been seen at Dorchester in 1775 show up also in the Taylor and Raphael articles written and published in the last twenty-five years. This seems to be the first problem of identity we face. Did Dr. Burk believe that the marquees used at Valley Forge were seen set up at Dorchester in 1775, and the campaigns that followed, until they finally reached Valley Forge in December of 1777 ? Additional documents clearly state and support that three new marquees were ordered in the Spring of 1776 for Washington. In the Life and Correspondence of Joseph Reed [William B. Reed, Philadelphia, 1847] the author quotes from correspondence dated March, 1776 from Joseph Reed (the General's secretary) to General Washington, "most of your camp equipage [from Fleeson] will be completed this week." This refers to the three new tents and other items ordered in the Spring of 1776. It must be these tents, and not the one's seen at Dorchester in 1775, as Burk repeatedly states, that Washington brought to Valley Forge. It also seems reasonable to assume that it was these tents that were possibly the ones sent for repairs while the General lived in the Potts house. And just maybe that is why Dr. Burk could never tell how he identified the marquees used at Valley Forge, "without a shadow of a doubt." So we can ask ourselves again the question, "Which of the marquees was used by Washington for several days at Valley Forge --the marquee seen at Dorchester in 1775, or the marquee ordered by Washington from Fieeson in 1776 ?" The answer is that we don't know, and we will probably never have an answer to the question. Although, we can always speculate about the marquee. We should keep in mind that Dr. Burk was in the midst of trying to promote and raise building funds for his Chapel in 1909, and we may therefore reasonably assume that he was not about to advertise to his Committee members, potential contributors or to the genera! public that he had just paid $5000 for just any old worn army regulation tent. For Dr. Burk, the tent was, and it had to be, "General Washington's Valley Forge" marquee! The tent was to be Burk's key focal point, the crowning glory, the most sacred item in his early collection of items to attract visitors to the Valley Forge chapel and exhibits. Yes, Dr. Burk was well aware of the marquee's promotional value as the "greatest relic of Washington's." Dr. Burk would use the marquee and its exhibition to generate future contributions as he attempted to raise funds for his growing vision. Dr. W. Herbert Burk was to write in American Westminster, "I planned to build a chapel, I hoped it might become a shrine." And with these words, we can recognize very quickly that he was not your typical small-community church minister from the country. Dr. Burk was known at the time, by both his friends and his detractors, as a very strong-willed man who would not back off from a challenge, as he demonstrated over and over again during his life time. The fact is that Dr. Burk was probably a dangerous man, if your definition of the word dangerous means that your ideas do not follow the norm, and that some people may see them as a threat. Dr. Burk was a man driven internally during his life time, and in many ways self-possessed by a dream and a vision that only he could see. As I write these words I question myself: Am I overreaching, exaggerating or intentionally trying to degrade and make Dr. Burk into a villain? No, far from it. The fruits of Dr. Burk's vision and dreams still stand before us, perhaps not yet completed or as grand as he would have preferred, but they remain there on the hill overlooking the hallowed grounds, for each of us to see, experience and visit today.

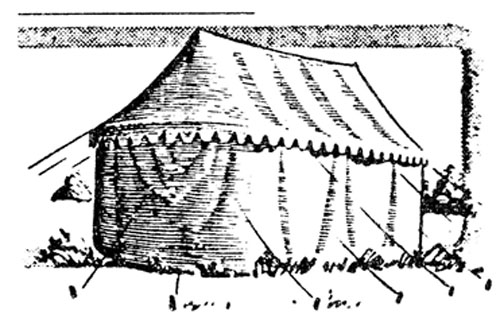

About the cover: The illustration of General George Washington's Marquee on the cover of this issue is from a post card issued in 1911 by Dr. W. Herbert Burk. |