|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 40 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: October 2003 Volume 40 Number 4, Pages 131–138 September 11, 1777: Washington's Defeat One of the pleasures of writing a book on local history is having opportunities to talk with members of historical societies and others who are interested in our heritage. On June 29, 2003, I spoke to members of the Tredyffrin-Easttown History Club at the Easttown Library. The room was full and I thank everyone connected with the History Club for offering me the opportunity to address your group. I had a wonderful afternoon. My talk was on my book on the Battle of Brandywine titled September 11, 1777: Washington's Defeat at Brandywine Dooms Philadelphia. White Mane Publishing of Shippensburg, Pennsylvania, released the book in January 2003. After two months the first printing was sold out and as I write this article the book is almost half way through its second printing. This article, as requested by the History Club, details some of my experiences in writing September 11. As a child, my parents introduced me to the Brandywine Battlefield Park in Chadds Ford. My parents took my brother, sister and I to the park for picnics. The park is a great place to roam around the hills. Years later I took my daughters, Megan and Melissa, to the park. I also spent three years on the Board of Directors of the Brandywine Battlefield Park Associates, the non-profit organization that helps with the promotion of the park. Two of those years I spent as President of the organization. Through my early adult years I returned to the park and attended re-enactments put on by the Brandywine Battlefield Park Association and picked up some information about the battle but I was unfamiliar with most of the details. I began researching the battle after an experience I had while working for the Daily Local News in West Chester, Pennsylvania. For more than twenty years I worked there and spent the last part of career as Managing Editor. For most of my time at the newspaper I wrote weekly columns on whatever topic struck me that week. I've been interested in all facets of Chester County history and history in general since I was a boy and I've collected old newspapers, books, postcards and other paper ephemera connected with history, especially county history. In the mid-1990s I offered a bid on a lot during an auction on paper material. The auction catalog listed a newspaper from New England printed in the early 1800s. The paper had a first-hand account of the Battle of Brandywine written by an unnamed member of Count Pulaski's cavalry. I tendered my bid and waited to see if I won the lot. I was high bidder and in a few days the newspaper arrived at my home. The account by the cavalry officer was descriptive and full of energy. He recounted his day during the battle and rushing from one section of the field to another section under Pulaski's guidance. I wanted to share the details of the article with the readers of my column but I needed to know more about the Battle of Brandywine. I went to the Chester County Book Company in the West Goshen Shopping Center and asked for a book on the battle. The bookstore has volumes and volumes of books on just about every imaginable subject. To my surprise, the clerk told me no such book on the Battle of Brandywine was available for purchase. To say the least, I was surprised. There have been pamphlets and magazine and newspaper articles written on the battle along with guides, but no history on the battle outside of a volume written as part of a series on the Revolutionary War for the bicentennial of our nation. Most history books either briefly mention the battle or totally ignore it. The battle also receives little play during television documentaries. The Battle of Brandywine was the largest land battle of the war and more than 25,000 troops, including George Washington and other notable leaders, fought along and near the Brandywine River in Chadds Ford. The historical event deserved more coverage. A book was needed on the Battle of Brandywine, not just my column. After my trip to the Chester County Book Company I began my six-year trek that took me to libraries and historical organizations throughout the eastern portion of the United States and a trip to England. At the time of my visit to the bookstore I was completing the researching and writing of my first book on Fort Delaware with co-author Dale Fetzer. Stackpole Books released Unlikely Allies: Fort Delaware's Prison Community in the Civil War in 2000, but most of our work had been completed two years earlier. I then had time to begin the research and search for a publisher. My editor at Stackpole was not available to work on the Brandywine project, so I decided to look for another publisher and contacted White Mane Publishing. White Mane was one of three publishers interested in the Fort Delaware book and they were interested in publishing the book on Brandywine. After a short negotiation period, I signed a contract with White Mane Publishing. An ambitious publishing date was September 11, 2002, the 225th anniversary of the Battle of Brandywine. I knew a big celebration was being planned at the Brandywine Battlefield Park and the event and the expected crowds presented a great opportunity to introduce the book. Even with my best efforts to complete the research and the manuscript and forward the project to White Mane, the publisher didn't have enough time to do the editing and printing. The book was released three months after the anniversary celebration. During the writing and editing process several working titles were applied to the book. Calling the book “Brandywine” wasn't an option. First, the title had been used. And, it wasn't descriptive enough for readers to know what text they were buying. Was the book about the Brandywine River? Maybe, it was about the Brandywine school of painting and some of its famous painters, such as Andrew Wyeth or Howard Pyle? Since most history books and television documentaries about the American Revolution failed to mention Brandywine, or only briefly mention the battle, I was safe in assuming most people wouldn't associate Brandywine with the subject of my book. The initial thought on the title was “Battle of Brandywine.” That was a start, but again it wasn't overly descriptive and didn't designate a war or geographic location. I wanted to include George Washington in the title since that would be a draw for some readers. Brandywine was a defeat for Washington, so that fact should be indicated. The battle was the major conflict of the 1777 Philadelphia campaign and led to the Continental Congress abandoning Philadelphia. Those facts should also be included in the title in some way, but I didn't want a title that would take about five pages to document. The title began to take shape: “Battle of Brandywine: Washington's Defeat Dooms Philadelphia.” The title wasn't perfect but it was getting to the point. The researching, writing, editing, and publishing of the book took about six years. While deep into the writing of the book – the deadline was only several months away – a tragic event took place in New York City: the terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center. The date of the tragedy, September 11, 2001, won't be easily forgotten by any American. The Battle of Brandywine took place on September 11, 1777. The date presented a marketing opportunity and also an opportunity for a marketing disaster. I didn't want to seek recognition or profit on the back of the national tragedy. This concern also was widely discussed by the members of the Board of Directors of Brandywine Battlefield Park Associates. I was President of the Board at that time. I didn't want a direct link to the New York disaster and my book and the BBPA didn't want to do the same in the promotion of the historic park. The date of the battle did take on a special significance after September 11, 2001. The book title was changed to September 11, 1777: Washington's Defeat at Brandywine Dooms Philadelphia. The date of the battle was simply stated and no reference was made to New York City. Many people have since commented on the happenstance of the same month and day. Most people didn't know the date of the Battle of Brandywine but some now remember the date. The researching of the book posed a different set of problems. I tackled the research the same way an investigative newspaper reporter tackles a writing assignment. I didn't want to take any information on face value. I wanted to double check sources and verify all of the information I found. Relying on something written years after the event by a veteran with a faulty memory isn't a good idea and is a questionable source of information. Relying on second-hand material also isn't a good habit to have for those researching history. There was conflicting information on everything from the number of troops involved in the battle to the general to blame for the defeat. Different researchers and historians also have different interpretations of some of the events surrounding the battle. The problem with verifying information is that the paper trail is growing thin after 225 years. A lot of the paper has been lost or destroyed over the years and many pieces of paper I found were almost unreadable. There are a number of researching land mines out there ready to explode in the hands of even a careful author/historical researcher. A good example is one of the first “facts” I researched. In some publications, including a recent one by the state government, and during talks by some who give tours at the battlefield, visitors and readers are told John Marshall, future United States Supreme Court Justice, fought at Brandywine and was wounded. I thought this would be a great place to begin my research. A famous figure in United States history, John Marshall, must have written something about fighting at Brandywine and being wounded. I began by reading Marshall's papers and autobiography. I read other books written about him and contacted some Marshall scholars in Virginia. Clearly, Captain John Marshall of Virginia fought at Brandywine. Marshall, who was 13 days away from his 22nd birthday when the Battle of Brandywine took place, was a member of Brigadier General William Maxwell's light infantry. General Washington formed the light infantry unit as the Philadelphia campaign began in late August of 1777. Maxwell's men, including young John Marshall, fought at Cooch's Bridge, the only Revolutionary War battle in Delaware on September 3, 1777, just eight days before the Battle of Brandywine. Colonel Thomas Marshall, John Marshall's father, also fought at Brandywine with the 3rd Virginia and was one of the American heroes in the fighting during the late afternoon hours as he helped delay British General William Howe's advance from Osborne's Hill towards the Birmingham Meeting House. While doing the research, I couldn't find any information on Captain John Marshall being wounded. You would think if he were shot, he would have mentioned the fact in his autobiography. I checked again with some Marshall experts and dispatched my brother, who lives in Williamsburg, Virginia, to go to the College of William and Mary library to search. No information on the wounding of John Marshall could be found. This was a vexing problem. I didn't want to include the story about the wounding of Captain John Marshall in the book if it was untrue. One day, while doing research at the Chester County Historical Society, I came across a diary of an American officer, Lieutenant James McMichael, from Pennsylvania. He too fought at Brandywine. McMichael's diary entry for the early morning hours of September 11, 1777, said an officer in his unit – Captain John Marshall – was wounded. The location and the time of the wounding would place this Pennsylvania patriot fighting with Maxwell's light infantry. Now, at least, I knew where the reference to the wounding of Captain John Marshall began. A little research found that McMichael's unit also had a Captain John Marshall. This Captain John Marshall was from Washington County, Pennsylvania. There were at least two Captain John Marshalls in the American army at the Battle of Brandywine and the John Marshall from Pennsylvania, not the future Supreme Court justice, was wounded. The mystery was solved. Not all of the solutions to the apparent discrepancies were that clear. Several issues, because of the lack of corroborating evidence, are unanswered. One involves a situation that could have altered the course of the history of this nation and involved British Captain Patrick Ferguson and George Washington. Ferguson was an expert marksman, some say one of the best in the British army, who had invented the British military version of a breech-loading rifle. King George sent Ferguson to America in the summer of 1777 to try out his invention against the rebels. Ferguson fought at Cooch's Bridge against John Marshall and was in the vanguard of Hessian Lieutenant General Wilhelm Knyphausen's forces. Knyphausen's orders on September 11, 1777, were to drive the American forces of Maxwell from in front of Kennett Square back to and across the Brandywine River. The Hessian General was then to demonstrate in front of George Washington and hold the American army in check while the forces of Howe and Cornwallis outflanked the Americans and attacked the Americans from their rear. Knyphausen perfectly executed his orders. The morning of September 11 was hot and a fog enveloped the countryside. Howe and Cornwallis began their 17-mile march before daylight and soon after Knyphausen began his own march to the Brandywine. Ferguson's men helped push Maxwell back to and across the Brandywine. Ferguson's new rifle acted magnificently during the battle. During the late morning hours Ferguson saw an American officer gallantly leading his men and bravely demonstrating in front of the British troops. Ferguson was close enough, he later wrote, to have put three bullets in the American officer but decided not to fire. He felt the American officer was a brave man and deserved to survive. A little while later Ferguson himself was wounded in the right elbow. The next day Ferguson was being treated for his wound when he recounted his story of the brave American officer. A captured Colonial officer heard the story and stated the brave American was none other than George Washington. This is a great story, but is it true? When I started doing research for the book the state historical commission wasn't even sure if the Ferguson rifle was used at Brandywine. It was and papers found at the British Public Records Office in London proved its existence at Brandywine. Was George Washington almost a victim of Ferguson's new weapon? Maybe. The identification of Washington is based on Ferguson's description of the American officer and his uniform and the position of the incident and time of day. Also, since the original identification of Washington was made by an unnamed American it is suspect; unnamed sources always have credibility problems. Some historians believe the officer was not Washington because of the description of the uniform. This incident in American history at the Battle of Brandywine is unsettled. Obviously, to research the Ferguson/Washington story and all of the other circumstances surrounding such a battle as Brandywine, a lot of time and effort was expended. From the time I started researching the book until it was released by White Mane Publishers, six years had passed. I didn't work on the book every moment, but there were months were I did little but research and write and edit. One of the first tasks was finding information for the book. Where do you begin? I began by asking questions, reading history books and doing Internet searches. The Internet is notorious for having wrong information. There is no Internet editor to check facts and incorrect information gets posted every day. I didn't use information that was on the Internet, but I did use the Internet to track down leads and locations of libraries that contained relevant information. I also used the Internet to correspond with museum and library officials. In London, I had files reserved for me at the Public Records Office over the Internet. After arriving in London one morning and checking into our bed and breakfast, my wife Katherine and I took the Underground to the PRO office near Kew Gardens. The files were waiting and the research began. I thought it was extremely important to get the British side of the battle. Besides the PRO, Katherine and I spent a lot of time at the British Army Museum, located a few Underground stops east of where we were staying. For almost two weeks Katherine and I spent large parts of the day at either one or the other place searching through books, letters, and other documents. To be sure, we had some nice meals and took time to see some of the sights of the city, as London is one of my favorite towns. As for information on this side of the Atlantic, I discovered the David Library of the American Revolution in Washington Crossing, Pennsylvania. The library has an amazing amount of information on the American Revolution. The staff was friendly and helpful. As a matter of fact, every research library and museum and members of the general public were generous in their time and sharing their expertise. They saved me many hours by going through their collections and identifying useful information. As much as I could, I used original source documents. At times it was not possible and I had to rely on secondary sources. Some of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania resources included the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission headquartered in Harrisburg and the Brandywine Battlefield Park. The Historical Society of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia has a great collection of material. I also utilized some of the files at Lafayette College. Lafayette's first battle was at Brandywine and he was wounded late in the afternoon south of Birmingham Meeting House. Members of the Society of Friends, the Quakers, also provided records. The Quakers were influential members of Chester County at the time of the Battle of Brandywine. The Board of the Chris Sanderson Museum at Chadds Ford also freely offered their assistance. The Chester County Historical Society was a goldmine of information. The research library had files, letters, diaries, and other documents. The CCHS holds the key to many research projects involving the county. I'm also a member of the Board of Directors of CCHS. Illustrations and the design of front cover are important elements of any book. From the beginning I wanted Howard Pyle's The Nation Makers on the cover. It is one of my favorite paintings and is owned by the Brandywine River Museum in Chadds Ford. Jim Duff, Executive Director of the River Museum, helped me to obtain permission for the use of the painting. He also encouraged me to write the book. Representatives of White Mane then designed the cover and gained the approval of the River Museum. As for the inside illustrations I didn't want to use the same illustrations that appeared in other books and periodicals of Washington, Lafayette and the other historical figures. The Chester County Historical Society had a collection of photographs taken at the battlefield in the late 1800s. Even though taken a century after the battle, the photographs showed the area with dirt roads and came closer to the look and feel of the battlefield in 1777 than one could experience today. They were selected for the illustrations. After gaining the proper permission for using the illustrations and gathering the material, the hard work of writing began. Many hours in front of the computer screen resulted in the draft of the text. After working with White Mane editors on the final copy, the book was ready to be printed and distributed. In January 2003 the six-year book project resulted in September 11, 1777: Washington's Defeat at Brandywine Dooms Philadelphia.

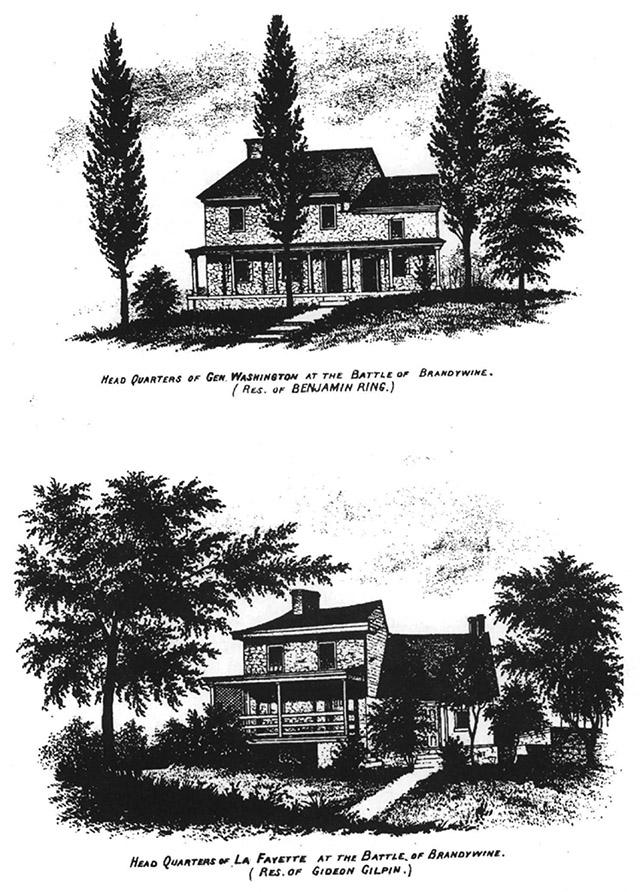

Artist unknown. J. Smith Futhey and Gilbert Cope. History of Chester County, Pennsylvania, with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts, 1881. facing page 71 |