|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

|||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|||

|

Source: Spring 2004 Volume 41 Number 2, Pages 43–55 THE BRITISH ENCAMPMENT IN TREDYFFRIN

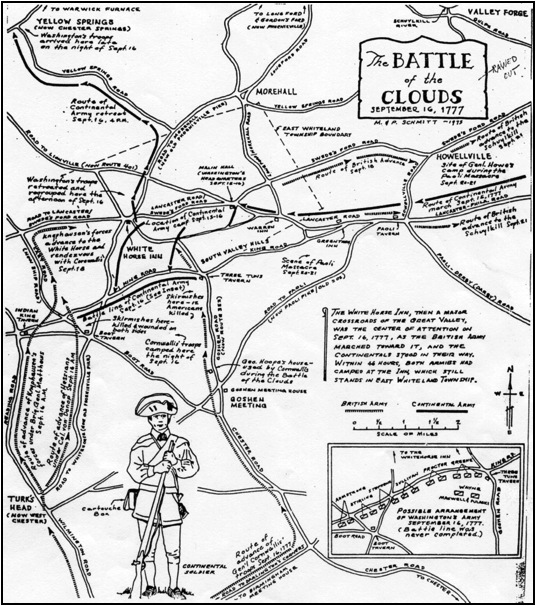

SEPTEMBER 1777 Hint for using the footnote reference links: Using the “Back” feature of your browser will return to the previous [Note] link location after you read the footnote. The Delete (Mac OS) or Back Space (Windows) keys often perform this function. This encampment is a very important part of local history because any time there is a military encampment of this size in the area, think of it as a rock landing in the middle of a pond. You can see ripples going out from the encampment. Today we date things from big events in our lives. We all know September 11th from now on. For those of us who are Revolutionary War historians, we always know September 11th as the day of the Battle of Brandywine. Not any more. I shouldn't say “not any more”—it has been superseded by another September 11th. For people who lived in this area, September 18 to September 21, 1777 was something that was left with them for the rest of their lives and their descendants well into the 20th century. One of this Club's founders, Franklin Burns, back in the 1930s started collecting data from some of these local families. What is frustrating about the data he provided was that he failed to identify his sources—where he got the information. It was obtained only through the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly starting back in the 1930s. One of the very first issues had a tour of this encampment and had drawings of many of the existing buildings. Many of the buildings have since vanished. There are many anecdotes of local families. I just wish he had written down “who” told him “what.” The trouble with local lore is that it is hit or miss. I can ask people in this room what they remember about Pearl Harbour or D-Day or something like that—what you were doing when that happened—and you can remember what happened as if it were yesterday. You can remember details, especially if you were in the middle of it. I've learned in doing research not to dismiss local folklore. You have to manage it very carefully and it takes a lot of work to either verify or discount it. Some of it is just patently ridiculous. When I worked at Valley Forge in the 1970s, someone asked me, “Where is the secret tunnel?” People heard there was this secret tunnel that was Washington's escape hatch down to the Schuylkill River in case the British came. I thought, “Give me a break!” There may have been a root cellar and the story evolved from that. Some of this is pure nonsense. But then there are other stories that stay in local families and perhaps someone in the family writes it down, whether it's in the flyleaf of a Bible or somewhere else. Some of you might remember a man by the name of Dr. Wood. Doctor David Wood came up to me after finishing a tour of Waynesborough and the Paoli Battlefield and he told me he had a great-grandfather who was in the Battle of Paoli and that he didn't know whether the information was accurate or not. His grandmother wrote it down in the 1870s as part of the family history. His ancestor served in the 4th Pennsylvania Regiment in the Paoli Battle and was on picket duty. He was badly wounded and almost killed. I entered that into my computer set up for information gathering for every regiment that was in the Battle of Paoli and, sure enough, I had found in Harrisburg several months before a certificate for a soldier that was wounded on picket duty at Paoli. He was in the 4th regiment and was certified for disability right at the end of the Revolution. This soldier was 17 years old and he was so chopped up he was rendered an invalid. He survived and it's signed by Dr. Wood's ancestor, Edward Fitz Randolph, so it confirmed that Randolph was not only at Paoli but that he was in charge of Picket Post #4 down at the Lancaster Road. There is the document that says it and the family history helps to confirm it. Here's another saga of another Paoli person. Catherine Simmons of White Horse Village told me Cromwell Pierce owned the lands where the Paoli Memorial Grounds and the graves of the soldiers are now and that her ancestor was Cromwell Pierce. She sent me some family material. Cromwell Pierce, Jr. was 5 years old the night the battle took place. In the middle of the night his family heard a knock at the door. They opened it up and a British Dragoon stuck a pistol in his mother's chest and demanded to know where her husband was. Her husband was a major in the Chester County Militia. Fortunately for him he was out of the house that night. The account says they searched the house, found a wounded American soldier, took him prisoner, and took him to the Tredyffrin camp. It turns out 40 years later Colonel Cromwell Pierce, now 45 years old, was one of the leading lights to have the monument put up at Paoli. Here's a 5-year-old kid the night of the battle and he never forgot that episode. This is the kind of stuff that brings history to life for people. Somehow people have the idea that since it happened in the past, you can't touch it, or that we can't relate to people 200 years ago who wear funny clothes and their hair is short or long or whatever. Well, it was not a costume party 200 years ago. They were real people. I don't have to tell you folks who belong to a history club—you know that kind of thing, but I often have to be reminded sometimes. I keep getting reminders of it and keep learning new things. That's why I love doing history. The British Army landed at Elk River, Maryland to begin its drive to take Philadelphia. They moved up through Maryland and Delaware and fought the Battle of Brandywine. They camped near Dilworthtown from the 11th to the 16th of September 1777 and on the 16th of September they moved up to Goshen. That is where the Battle of the Clouds took place. That encampment was before the Tredyffrin encampment. This past week we had our own Battle of the Clouds—I have never in my life seen rain like we had. I would guess we had 6 inches of rain overnight. That is what the Battle of the Clouds rain was like on the 16th of September. It was a tropical storm from remnants of a hurricane that came over the area. It stalled and raised the level of the Schuylkill River 12 feet in 12 hours and the river was up for the next 3 or 4 days. That is why the British camp here at Tredyffrin took 3 days. They were waiting for the River to come down so they could cross it. They sat out the storm in Goshen. Washington's army had pulled up in the South Valley hill in the vicinity of Immaculata College. The British were coming at them from two directions—up what is now Route 352 from Goshenville and up what is now Boot Road. The Battle of the Clouds was actually 2 separate skirmishes—between British and Hessian light troops against American light forces when this rain came down.

It ruined the American Army's ammunition. Washington withdrew back down into the Great Valley, and realizing that he was in a bad position, ordered his troops to withdraw to Yellow Springs. These poor guys had to slog up the North Valley hill—up Bacton Hill Road; up Yellow Springs Road. These were dirt roads. With that kind of gushing rain it took them 14 hours to go 6 miles. When they got to Yellow Springs, they were utterly exhausted. Some of them lost their shoes in the mud and were soaked through to the skin. British and American accounts tell us the number of the sick went up through the roof, as you can imagine. They called it “seasonal ague.” You would call it a real bad cold or flu. Of course there were no antibiotics, so a lot of the men got sick and it slowed both armies considerably. Washington lost all of his ammunition in that rainstorm. The British had waterproof cartridge boxes—one of these little minor details—and so their ammunition stayed relatively dry. But because the rain was so hard and the roads had gotten so bad, the British Army did not attempt to pursue Washington. They simply stayed in Goshen. They were there until the night of September 17th and the early morning of the 18th when they set out to go to the White Horse Tavern and then out to the Lancaster Road that was there in the 18th century. This is now west Swedesford Road, west of Route 401. The White Horse Tavern still stands. It is over at Frazier at Planebrook and Swedesford Roads, behind some silos back from the road.

The White Horse Tavern around 1900. You can see the White Horse and 2 other taverns in this area on the above map. The Warren Tavern was there when the British decided to move into the Great Valley. They went to where Swedesford Road meets present-day Route 401 and split into two columns. Lord Cornwallis took his column up the Lancaster Road —up Route 401 where it hits Route 30. Imagine it continuing straight up where the railroad tracks pass near the old Lincoln Highway and on up to the front of the Warren Tavern and then on to Green Tree, passing in back of Villa Maria Academy and then becoming the Lancaster Road again. Local legend claims that Peter Mather, who was the tavern keeper, was a Loyalist. He might have been, but doing the Paoli research I found no evidence of that. In fact, I found some evidence to the contrary—just one minor piece of evidence. Before he was innkeeper here he had been keeper of the Old Plough Tavern in Radnor, which, in 1744, had its name changed to The Sign of John Wilkes. John Wilkes was in

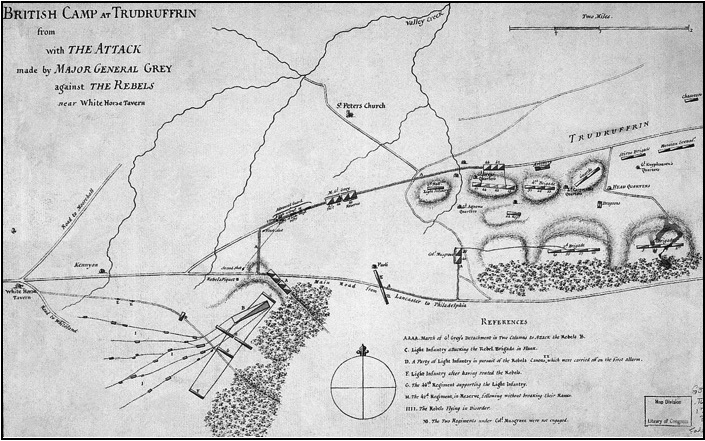

charge of the Whig faction in Parliament—a radical Whig. This would be equivalent to Richard Nixon being in charge of L.B.J. Tavern or something like that. Pick someone who is the antithesis and put him in charge. It doesn't make sense that Peter Mather would change the name of his tavern to a name that would be obnoxious to a Tory. He may have been a Tory. Local legend has it that he guided the British up to the battlefield, but there is evidence that he didn't do that—that he was asked and refused. The British accounts say nothing of that. Indeed, they said that it was a black-smith that they had forced to show them where the camp was. The next tavern is the old Paoli Tavern. At the time of the Revolution it was just a little 2 1/2-story house. A monstrosity of a wing was added in the 1790s. It stood about where the present day Paoli Post Office is. It was another landmark. Washington was sure the British were heading towards Swede's Ford, which is where Norristown is, because Swede's Ford was the best ford across the Schuylkill River between Philadelphia and Reading. Most of the fords, and there were 14 of them between Philadelphia and Reading, were very narrow. You had to go in the River, wander around a little bit, sometimes on to an island and off the other side. Swede's Ford was one of the few where it was shallow. It had a hard stony bottom and you could walk straight through. In fact, Washington was so sure that that was where General Howe was heading that he ordered a fortification built on the Norristown side and he ordered the Pennsylvania State Militia to hold the line there. When the British moved into Tredyffrin, they knew what was going on up there. They also had other options. Fatland Ford is down behind where the chapel is in Valley Forge National Historical Park. Between Fatland Ford and Phoenixville there were 4 crossing places: Pawlings Ford, Richardson's Ford, Long Ford and Gordon's Ford. Washington had to figure out just which way Howe was going to head. He presumed that Howe was after Philadelphia—but Howe could also go to Reading which was the Continental Army's supply depot. If Washington lost Reading he would be absolutely at the mercy of the British Army. As it was, our supply system was dreadful; but dreadful was better than none. The other option Howe had was to head to Lancaster—the largest inland city in America. There were lots of storehouses there plus about 5,000 British and Hessian prisoners of war. There was a war out there. Howe had a number of targets he could go to. How big was the army that came into Tredyffrin? When the British Army landed down in Maryland, they had approximately 18,000 troops. With all the other personnel that came with them, you're looking at an actual number of people of somewhere between 22,000 and 25,000. This whole county had 22,000 people in it. Just the British Army and its hangers-on doubled the number of people in Chester County. If you bring the American Army into it you can imagine the impact this would have on the local people. You also have to consider the way people dressed in the 18th century. These were rural Pennsylvania farmers. If you look at this area many of them are Quaker. There's also Baptist, Mennonites, a few Amish, and so on. Everybody was wearing plain farm clothing. You have to wonder how many people any of these residents have ever seen in one place. If you go to church or meeting on Sunday there are maybe 100 people there. If they went to market in Philadelphia—which might happen a couple of times a year if you are lucky—that is a day trip there and a day trip back. On a good market day in Philadelphia, you might see 5,000 people at the market. The British lost about 500 to 1,000 men in the Battle of the Brandywine. They sent 2,000 men with the wounded down to Wilmington. That leaves about 15,000 British troops. That's what came into this area and bogged itself down for 2 or 3 days. These are just guys who are not very careful. They are not just any old guys either. These are soldiers. They were not just any old soldiers. If you have the idea in your head that this was a cutesy little costume party—guys with powdered wigs and funny hats that kind of bumble along—forget it. These are combat troops. They were rough people under tight discipline. Their officers were aristocrats who did not hesitate to have these guys beaten to a pulp if they looked at them crookedly. At the same time, because they were under such tight discipline, if a soldier got into mischief, depending who the officer was, he may look the other way and say, “Let the boys have some fun.” Or he may have them arrested and beaten. The first thing I want to focus on is what went on in the British encampment the first day the British were here. There are 3 period maps of the encampment —there may be others. On the next page is the most famous map of this encampment because it was engraved and published in London on July 1, 1778 and was drawn by an officer on the spot. It shows the White Horse Tavern and a house, which I think is still standing, on the Chester Valley Golf Course on Swedesford Road. It shows the Paoli Tavern, Swedesford Road and the British encampment. You can see the officer's quarters in a house that still stands on Old State Road. Old State Road continued up to where Conestoga High School is today, the other end merging into Contention Lane. A British battalion and the light infantry were camped where Syms clothing store is now located. This was 14,000 troops. When people tell you the British Army camped on that field over there, they did and every other field for the next mile and a half. This was a lot of people. They did not bring tents with them. Some of the British officers had tents and evidently some of the British Calvary brought light pup tents with them. Most of the British soldiers slept in the open or they built little shelters called wigwams—just lean-tos made of corn stalks, rails, brush, whatever. One of the big things they did to the area was burning the fence rails. Washington forbade his men to use fence rails for firewood, even though lots of them did. It is in the general orders over and over and over again—leave the farmers fences alone. He went on a tirade the day before the Battle of Brandywine about the destroying of fence rails. He said, “What a distress to farmers where fields are now exposed to ruin and the cattle and livestock escape in a country abounding in wood and men with hatchets in their hands.” The British Army had no such qualms about that. If you read the claims for damages, you will see hundreds of thousands of fence rails claimed. As a matter of fact, Anthony Wayne, in not letting his men remove the fences at Paoli, is one of the reasons for the disaster at Paoli. The men were being crammed into some small fence openings. The 2nd map is how Anthony Wayne saw the British encampment. [Note 1] It shows his camp at Paoli. It says “enemy, enemy, enemy.” The squiggly lines are the Great Valley hills. It shows Swedesford Road, Warren Tavern, Lancaster Road, Paoli, and Darby Road—the same Darby Road that runs in to Route 30. It becomes the present day Berwyn-Paoli Road. This is the road that runs down and becomes Old State Road, running down by headquarters. Anthony Wayne marks it on the map. This map is in the Library of Congress with some papers somebody found 50 or 60 years ago and hand copied and never used. When I was doing the Paoli research, I found this map along with the testimony of 15 officers on what happened at Paoli. It took me a year to find out who drew this. Fortunately I had a photocopy of this map when I was looking through Wayne's papers. Anthony Wayne's handwriting is on this map and what this tells us is where his pickets were located the night of the Battle

of Paoli. He was accused of not guarding the camp properly. Picket #1 is here by the Paoli Tavern—in all 6 pickets are shown. This map was drawn in October of 1777 for Wayne's Court of Inquiry. This was part of the evidence that proved he had guarded the camp properly. Andre's map [Note 2] has north pointing downward. It shows Swedesford Road, Contention Lane, Howellville Road up to Cassatt Road, and Howell's Tavern (General Gray's quarters). On the South Valley hills are the 1st Brigade, 2nd Brigade, 1st Grenadiers, 2nd Grenadiers and, at headquarters, the 16th Light Dra-goons. Cornwallis's group moved up Lancaster Road to the heights. Here's where this map is so extraordinary. I was doing research in England and I found a diary of a British officer in the campaign up in Northern England at the University of Durham. At the top he says, “18th–marched from [blank in diary—probably Goshen] and on 20th marched from Tredyffrin at 3 in the morning about 3 miles. Along the banks of the Schuylkill River several shots fired by the rebels across the river” and so forth. The officer was a young guards officer and, by coincidence, the next year going through the Guard's Museum in London, of all the random people hanging in the case, there he was. His name was Lord Cantelupe—William Augustus West, the Viscount Cantelupe, and his father was Lord De La Warr. He was a descendent of the man the Delaware River and Delaware Bay were named after—Thomas De La Warr. In a little miniature there's a little coronet with the script letter “d” underneath. His father died in November, 1777 and he became Lord De La Warr. He went back to England in 1778 and after that he had the little miniature done. The reason this is so crucial is that here in his diary we have a drawing of the Light Dragoon encampment of the September, 1777 encampment. The illustration on the cover of this issue of the Quarterly is a landscape taken from the Guard's encampment. And when you look at what is here, you see a combination of these little wigwams plus these little lean-tos. We also see some horses, one of them drinking from a stream and we see a nice wooded area. There is a tree line. Up in these trees are other British encampments. The original of this picture is only 4 x 6. When I had it blown up it showed horses tethered to a fence. There is one other little watercolor in the diary. It is on the top of the next page and shows a battery the Rebels opened on Brandywine Heights on September 11, 1777 in the township of Birmingham. These are probably the Guards going into the Battle of Brandywine since this man was a Guards officer. There is a line of British troops along a fence firing away at American troops. You can see skirmishes here and there. This is what got me. This watercolor is obviously what you might call a generic battle team. But the watercolor on the cover is not. Because when I go to Andre's map I see a brigade of Guards. Here is Contention Lane. Look what we have—here are the Light Dragoons; here is Trout Run. In other words, this British officer did not make this up out of his head—he sat down and painted what was in front of him. How do I know that? When you start look-ing at the watercolor on the cover very carefully and you see that stream and you also see trees and right in the middle of all the foliage, there is a dead tree. It struck me—why would he draw that dead tree unless it was there. Then you do a bit of investigation. What were these Guards doing in this encampment and how long were they there? It turns out the Guards were at this location and they were there exactly 1 day —September 19th. The British got into this camp late on the 18th and early on the morning of the 19th. On the morning of the 19th there was an alarm from the British troops that had gone over to Valley Forge earlier. Early on the morning of the 20th—about 1AM—these Guards were sent over to Valley Forge.

This was 3 months before Washington's winter encampment there. There was a store-house there with American Army food supplies. A British patrol went over there. It turned out the British patrol that went over there was the 16th Light Dragoons because they were on horseback. There was a little skirmish over there—Light Horse Henry Lee and 8 Dragoons. The American Army had sent 8 men to move 3,800 barrels of flour across the Schuylkill River. Each barrel weighed 200 pounds and, using 2 rafts, it should have taken 5 days. Each side lost a horse and one American died. Alexander Hamilton was also there —it was his horse that got killed while crossing the river on a raft. What has that got to do with this encampment? We find that in this British diary, the Dragoons were over at Valley Forge until about noon on September the 19th, because at about noon the report got into the British camp that the men at Valley Forge were about to be attacked by the men in the American Light troops under General Maxwell. So immediately the British Grenadiers and the 1st battalion of the British Light Infantry were sent over to Valley Forge. The Dragoons then came back to this encampment. This means the Dragoons were in this encampment on the afternoon of September 19th. They were up all the previous night involved in the skirmish. They were up at the tree line. Look at the shadows of the trees in the drawing. The sun is in the west. It was a warm day in the 70s and there is not a soul in sight. We have a company of sleeping cavalry men. This is only conjecture. This was not in the diary. We do know that some of these Dragoons went out later that evening and went on a raid all the way out to Radnor and Marple Newtown and then all the way back. They brought 150 horses in. Evening in those days meant any time in the afternoon. This was in a full moon period and they had plenty of light to carry out their mission. That British raid is an example of some of the activities that went on during this British encampment. Cantelupe left this camp a few hours later—he was there only one day. The painting on the cover is a “snap shot” of the 18th century. I asked the Chester County Historical Society what was the earliest image of a Pennsylvania landscape they had. They had nothing that was pre-1800. The two drawings reproduced here are pre-1800 images. It was just an obscure thing out of a British officer's diary that produced these images. In answer to a question about the Guards: the men guarding Buckingham Palace today are called the Grenadier Guards. Grenadiers were introduced into European armies in the late 17th century. During the American Revolution it was a designation for the men who threw hand grenades—usually the tallest men in the regiment. Originally they wanted men for this who were very strong, very tall, and not too bright. The grenadier had to light the fuse and blow on it, then chuck it from about 50 yards. The grenades often went off prematurely. They gave the tallest men little pointy hats and discovered that if you put a tall hat on a tall man it makes them look even bigger. By 1768 the British updated their uniforms. The Grenadiers wore bearskin hats. Every regiment had one company of Grenadiers. On a campaign they would take the Grenadier companies from their regiments and put them together into Grenadier Battalions. These were shock troops with a rather rough reputation. These men would be held for key positions in battle. When the going got tough, the Grenadiers would be sent in. There were 2 battalions of Grenadiers, or 1,200 men, in the Tredyffrin camp. Today all Guards are called Grenadier Guards. The British Army held 3 courts martial at the Tredyffrin encampment on September 19, 1777. [Note 3] The Morning Orders for the first one begins: “A General Court Martial, consisting of 3 Field Officers and 10 Subalterns from the Brigade of Guards to assemble immediately in front of that brigade to try Robert Hicks and Thomas Burrows, private Soldiers in Lieut.- Col. Sir George Osborne's Company.” Hicks and Burrows were caught plundering in the last encampment —the one near Immaculata College. We have Sir George Osborne's testimony of what he saw. Here is part of it: ...having found several Grenadiers of the Guards absent at the Morning Roll calling, and having reason to imagine that they had gone to a house at some considerable distance from the front of the encampment, Captain Fitzpatrick and he walked on to the corner of the wood, to endeavour to find if any of the Grenadiers were coming that way with plunder, and in a very short time, Captain Fitzpatrick, who had stopp'd the two prisoners, call'd to him, and he (the Witness) found upon them the plunder mentioned in the annexed List, and the Prisoners very much intoxicated with liquor; some of the inhabitants came soon after to claim some of the goods, and he sent to the Quarter Master, that he might safely deliver them, taking a Receipt for them, as it was impossible to carry inhabitants from one place to another. . . . Then Fitzpatrick testifies and this is the kind of information that tells you just how far these men had gone from camp. Next, George Breecher, Quarter Master of the Guard, deposed that some soldiers had been pillaging and that Mr. Wilson, Adjutant of the Guards, ...gave him a bundle containing the things that had been taken, that soon after some Country men informed him that three Soldiers had been at his house, and had robb'd him, upon his asking them, what had they been robb'd of, one an-swered that he had lost a leathern Jacket, a pr. of breeches and a pair of Stockings, as also some Shirts, and upon his opening the bundle he found therein among other things, a leathern Jacket, a pair of breeches, and a pair of Stockings, which the Man claim'd as his property, and he accordingly gave them up to Evans Evans, who signed the receipt produced in court. I went down the lists of local people in all the townships looking for Evan Evans. The only Evan Evans I found was in Uwchlan Township. In this encampment the Guards were up on the South Valley hill just west of Ship Road. Apparently these men went up Ship Road, and as Sir George tells us, they went a considerable distance from the camp—about 5 miles —and robbed the Evans' house. The funny things to hear are the prisoners' explanations. One prisoner said that they went a little ways from their camp in search of some fence rails and met some soldiers from the Light Infantry with bundles, which they dropped upon seeing Sir George Osborne coming. Each of the prisoners picked the bundles up not knowing what they contained. They also found some bread and liquor, the latter of which they drank. Prisoner Hicks said he was sober but Burrows acknowledged that he was in liquor and did not know what he said to Captain Fitzpatrick. The court considered the evidence of Hicks and Burrows and found them guilty of the crime laid to their charge and each to receive 500 lashes on their bare backs with a cat-o-nine-tails. The 2nd Court Martial of that day was of Thomas Burford and John Jackson, private soldiers, and Richard Jones, Corporal, in Lieut. Colonel O'Hara's Company of the Coldstream Regiment of the Foot Guards. They were accused of plundering. Witness Adam Erd, Corporal in the Regiment du Corps in the service of His Serene Highness the Landgrave of Hesse Castle, was a Hessian soldier who testified against British soldiers. They had an interpreter, Captain William Faucett. Erd said that ...the prisoners came last night to the Guard which he commanded, and asked where the Grenadiers were, that he asked them what they had and what they wanted with the Grenadiers, and they answered that they had silver to sell, which the Witness desired they show him, and they produced a silver Tankard, twelve [silver] Table Spoons, a Soup Spoon, and two pair of tea tongs. . . The Hessian soldier said they asked him for 12 guineas for the tankard. Twelve guineas was more than a year's pay for a soldier, upon which the Hessian soldier felt himself obliged to relate the entire matter to the Lieut. Colonel, which he did after the tattoo was beaten. The Lieut. Colonel ordered him to confine the men and bring the plates to his tent. These men went on the defense and said that they had found the silver buried at the last encampment. This might well have been true in that the locals hid their valuables all over the place, but it's just amazing—here was a Hessian soldier who felt it was his personal obligation, after he heard what the price of the tankard was, to report these men to his Colonel. There was another corporal, Nicholas Friberg, in the same regiment who said the same thing and Burford said he found the plate buried in the ground near where the army was last encamped. He and Jackson went about 200 yards in search of boughs to cover their huts. There is proof again that these soldiers were building little wigwams. He told Corporal Jones that he had got something of value and asked him to take a walk to the Hessians. Jones asked them for what purpose. He replied, to sell some plate he had found because he was informed that the Hessian Grenadiers would buy anything. The men were found not guilty because their explanation was that they had found the plate buried and no civilians came forward and claimed the silver. One of the local stories in Henry Woodman's book about Valley Forge actually comes from Woodman's mother. [Note 4] She lived over on Old Gulph Road. She said that some Hessians had come over there and searched the house and that her mother had hidden some silver spoons in the apron of her mother who was 90 years old and couldn't speak and couldn't hear. It was very strange. The Hessians came in and saw this poor old woman literally tied to a chair to keep her from falling over and they all came up and bowed to her and said very polite things to her in German, and they never searched her. They ransacked the rest of the house. The problem was that they were told that if any military items were found in the house, they were to burn down the house. They opened a drawer and found some cartridges that someone had forgotten. They didn't burn down the house but they did tear apart the feather beds and other things. But what Woodman's mother said happened earlier was that one of her neighbors, Mrs. Dewees, Colonel William Dewees' wife, had brought some trunks over to the house and asked her to keep them in her house—that they were personal possessions and that if the British came down to the Forge they would lose them. Woodman's mother had asked her if there were any military things in the trunks and was told that there were not. It turned out that Dewees' uniform was in there along with his sword and other military regalia. When Woodman's mother afterward found out, she took the trunks and threw them into a quarry. Woodman's mother accused Mrs. Dewees of putting things in her house that the Hessians might have found and that if they had, they would most certainly have burned her house to the ground. Those kinds of episodes, those little nasty vignettes, happened. And yet houses were not burned down left and right in the area. Some people lost possessions. When you have an army of 15,000 men, there are pilferers in every army. Some local Loyalists were plundered. Reverend Currie, who lived over on Yellow Springs Road in what is now Stirling's Headquarters, was pastor of St. David's Church. He was also pastor of St. Peter's Church in the Valley. He was a Loyalist. Three of his sons were in the American Army and he was really torn by the whole business. He stopped preaching in 1777. He listed things that had been plundered from his house. The common soldiers on both sides didn't care whose house it was. Joseph Plumb Martin, often called “Private Yankee Doodle” tells the story in his memoirs of the American Revolution [Note 5] that when he left Valley Forge to go over to Downingtown, he and his company stopped at a house. He said the woman of the house was kind of crabby and one of the soldiers offered to sell her a shirt for some vegetables, calling it “sauce” for dinner. As soon as she left the room, the soldier saw where the shirt had been thrown and he helped himself back to it. Not only that, the soldiers went down to the basement and found some hard cider and they made very merry. Martin was on a foraging detail during the whole of the Valley encampment and he told it flat out. He said, “Don't blame the soldiers. When you are starving, you don't care whose house it is. Chicken is dinner. It's not a Tory. It's not a Whig. It's dinner.” The food that the armies brought with them was dreadful—pickled pork, and a lot of it gone bad. They were desperately looking for flour. That is one of the reasons they attacked Valley Forge— 3,800 barrels of flour were there. They had livestock, fresh meat, cattle and sheep following this army by the thousands. The officers couldn't watch every-one every minute. They tried to make an example of every plunderer caught. When they left the area—15,000 men—they left it a shambles and the local people would never forget that. This neighborhood hadn't known what it was in for. When the American Army showed up in Valley Forge, they were there for 6 months. If you came back after they left the area, you would not recognize it. The trees alone disappeared in a 3 mile radius from what is now Valley Forge Historical National Park, as did all the fences. It took years for the place to recover.

Tom McGuire teaches American history at Malvern Preparatory School. His talk here was presented at the September 28, 2003 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. It was transcribed by Nancy Pusey. |

|||