|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: Spring 2004 Volume 41 Number 2, Pages 63–68 TALLY HO A Tale of a Thanksgiving Day Chester Valley Hunt About 1910

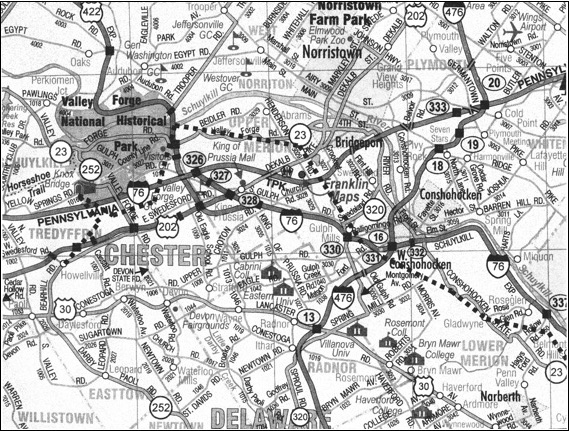

INTRODUCTION I recently found, among family archives, an intriguing report of the 1910 Thanksgiving Day Meet of the Chester Valley Hunt. Fox hunting had been a recognized sport in this area ever since the post-Revolutionary War period. Hunts established in this period were the Radnor Hunt, the Pickering Hunt, and the Chester Valley Hunt (C.V.H.). I remember seeing, in some archives, a copy of an invitation to the annual dinner of the C.V.H. dated in the 1870s era. This invitation has apparently been lost. Up to 1930 the C.V.H. held annual dinners at the King of Prussia Inn but the hunt passed out of existence in the 1940s. Radnor and Pickering are still very active hunts. The King of Prussia Inn was also a popular spot for post-hunting libations. There were no rules then for drinking and riding! The epic hunt, described in the attached report and traced by the dotted line on the accompanying map, was headed by William Currie Wilson, my great uncle. “Uncle” Billy, as he was known in the family, was an avid horseman and served as Master of the Hunt for a number of years. His farm, “Maplecroft,” adjoined the King of Prussia Inn. His middle name “Currie” was descended from Parson Currie, the priest sent by St. Davids Cathedral in Wales to serve St. Davids and St. Peters parishes in the Chester Valley. He married one of the Walker girls from whom numerous Walkers and Wilsons are descended. Meets of the C.V.H. were regularly scheduled during the fall and winter hunting seasons through the 1930s, and started at various farms. The hounds were kenneled at the Quigley farm near Berwyn. Participation was open to anybody who could ride. However, participants were expected to make donations for the maintenance of the pack of approximately 10 pairs. [Hounds are always counted by twos, hence the terms “couple” or “pair.”] By this time the pink coats and top hats worn by C.V.H. riders had been replaced by tweed hunting coats and black riding helmets. However, Radnor and Pickering still enforce the formal hunting garb. Because some riders were less skilled in tackling the jumps, the whipper-in [assistant to the huntsman, usually out on the edges of the group] would remove the top rail from the fence, making the jump less formidable. This assistance also permitted me to follow the hunt on my pony, “Lucky,” who could clear the reduced jump height. The construction of the Pennsylvania Turnpike and Route 202, coupled with rampant residential construction, made hunting impractical. Approximately 4,000 to 5,000 acres are needed for hunting activity. In another generation even Radnor and Pickering will probably be squeezed out and this graceful sporting activity will disappear from the Chester Valley area.

THE 1910 THANKSGIVING DAY MEET In those days the American Hounds of the Chester Valley Hunt were kenneled on the small farm of Jack Pechin, the field hunts-man, near King of Prussia. Followers of the hounds held meetings or took their ease at the King of Prussia Inn, which is still standing, but at a different location. Hounds were tended by Lige Brooks, kennel huntsman. They met for hunting at the farms or estates of members – those fine old 18th century houses of native stone: some pointed with mortar, others encased in stucco-like plaster, sand colored or white, with shutters or blinds, usually of very dark green. Most were surrounded by groves of shade trees, among which the silver maple was the favorite. There were still very few motor cars. Fences were not paneled and foxhunters jumped line fences. Wire was little used and very unpopular. There were some stone walls and a few plank fences, but mostly post-and-rail, snake fences, and cut-and-laid mockorange hedges. The sport was rugged, but as dedicated then as now. Most in the field were men, except for a few Amazons and some hard riding ladies on sidesaddle who lent dignity and polish. “Uncle” Billy's epic hunt was on a Thanksgiving morning, and several C.V.H. fox-hunters ate cold turkey that night or went hungry, and a few found their legs under the tables of Good Samaritans far from King of Prussia. We hope that Charles James Fox had a warm hen or goose for his Thanksgiving dinner. He earned it! It was a clear, cold sparkling morning with a bright blue sky and a gentle breeze from just north of true west. The fixture card called for the meet at Cressbrook Farm, once occupied by General Duportail, the French engineer with Washington. Just before he went to the stable to mount his good half-bred hunter for the holiday meet, Billy had a call on the primitive telephone. It was the foreman at the quarry and stone crushery at Howellville. “Mr. Wilson,” he shouted into the dubious instrument, “there's a big dog fox a-sunnin' himself on top of our coal pile here. Thought you might want to come and chase him.” The M.F.H. thanked him and hacked the half hour to Cressbrook. He conferred with Jack Pechin, the huntsman. When the Field had assembled at the old mansion surrounded by giant silver maples and great hedges of clipped privet, they trotted the hounds out the Wilson Road and west on the Swedesford Road to Howellville. Sure enough, on top of the mountainous pile of coal – anthracite pea used to generate steam to operate the limestone crushers – was a big dog fox, bright orange and deep tan with some white on his pads and brush and a canny grin on his mask. He regarded the hounds and Field contemptuously and without the slightest apprehension. The Field was tremendously excited, and the huntsman was mighty perplexed. Just how does one push a fox from a high coal pile? Jack gave a great yell. Nothing happened. He tried to wave the hounds up the pile. They chose to misunderstand his gestures. He blew his copper hunting horn. The whipper-in and every one else with a whip cracked them until it sounded like rifle practice. Still nothing. “Dismount, Jack,” said Billy Wilson, “and see if you can cast the hounds up the pile with you.” Jack handed his reins to a groom, and each step he climbed he slid back three-quarters of one. Hounds did try to climb with him and were finally encouraged to go ahead of him. The fox had watched all this with interest and amusement. He gave a sort of yawn, stretched slowly, and jogged confidently down the north side of the pile. Down tumbled Jack with no dignity; on went the pack screaming. Billy held up the Field until his huntsman had remounted. The fox loped easily away and set his course into beautiful Chesterbrook Farm. Hounds opened like a symphony orchestra con spirito and every one flew at the cut-and-laid hedge into the 750-acre farm. Charles James Fox continued northeast into the Wilson Farm where General Lafayette resided during the winter of 1777-78, and then swung across where the turnpike is now. There he turned left-handed (a fox never turns right or left always right-handed or left-handed). He crossed the Valley Creek into Valley Forge Farm, just south of the Covered Bridge and then turned right-handed and raced through the open meadows of Valley Forge Park. Someone headed him and he turned right-handed through Brookmead Farm, took a little swing across Walker Road into Many Springs Farm, and then left-handed again through Glenhardie Farm back into the Park, crossed the Montgomery Pike and circled clockwise above Port Kennedy. He was viewed many times and the thirteen-and-a-half couples of American Hounds followed in beautiful cry across the autumn landscape, but instead of gaining on him they fell a little behind with each additional mile. The fox was out of sight, but hounds still flew with their noses to the ground. While the day was chilly the ground was warmer, and misty patches were seen in the brown and gray hollows. Scent was obviously strong and there was little distraction except for cur dogs trying to join the pack here and there. (Any dog except a hound while hunting is a “cur dog.”) The line ran just south of east, passing the Port Kennedy Presbyterian Church with its well-filled graveyard. Charles turned right-handed at the old mill beside the single-track Reading Railway line and ran near the stone bridge and big barn uphill past a large orchard, still bearing a few winter apples, to a high point overlooking Norristown. There another fox crossed the line, a slim vixen much darker than the hunted fox. A few of the younger hounds faltered, but Jack's voice and horn and the crack of the thong of the whipper-in backed by a few of the Field gave the sinners religion and on they went after “the coal pile fox.” The line led southeast across the course of the current turnpike and crossed the Swedesford Road—now Route 202—east of King of Prussia and southeast across a small valley and up a hill crossing the Trenton Cut-Off of the Pennsylvania Railroad, then parallel to Henderson Road, up and down some steep hills until north of Gulph Mills, hounds checked and scent seemed to evaporate entirely.

The Field was beginning to show wear and tear. A couple of top hats were accordioned from branches or spills. No one asked. One sidesaddle rider had lost her veil but, flushed and happy, was keeping up. One hunter had cast a shoe and the rider pulled out to seek a blacksmith. Mud had spattered pink coats, white twill, and white buckskin breeches. Several unfit horses had been obliged to pull out. A couple of Chester County farmers on make-do hunters, who worked in harness at other times, found Montgomery County too far from the barn. Here and there a sandwich appeared from a pocket or case and flasks were used and shared. A few new foxhunters had joined the chase – residents or farmers enjoying a Thanksgiving hack, happy for the unexpected diversion. While fences had been few, they had been stiff and the up and downhill going was exhausting. At least two men had been down, but remounted. Jack Pechin cast his pack “all around his hat” and up through the open cathedral-like beech woods on the hillside and down into the dense gorse by the stream. One hound opened with a timid whimper, then two or three spoke hesitatingly to the line; finally the glorious chorus resumed and off they went again, east and southeast, with hounds in melodious cry. The pack and Field crossed the Balligomingo Road and raced across where the Schuylkill Expressway now runs, across what is now Calvary Cemetery and up through the Stoke Poges section near Villanova. On they flew, south of West Conshohocken, across the Spring Mill Road and parallel to Conshohocken State Road, and into the farms and estates near Gladwyne. It may have been called Merion Square then. Again the hounds checked and scent seemed to fail. Nothing was heard but the crackling of the dried leaves clinging to the red oaks. Jack's skillful cast could not pick it up. In the distance a flock of sheep was visible and beyond them a circling flock of chattering crows. A country man waved his cap. The whipper-in galloped to him. He announced that the fox had foiled his line by walking among the sheep. He showed the direction and hounds slowly owned the line again. It was now close to half-past three. Hounds were tiring. Horses and riders seemed cooked, but Charles James Fox was still up ahead and Billy said to Jack, “I hope we mark him to earth. I really don't want to kill him – he's too game. If we get close let's whip off.” In the estate country more riders joined them. The word had spread that a classic run was on. Some others who had started at Howellville had to drop out from sheer exhaustion. Billy found later that some got home the next day. The day continued bright and hounds were still trying, although their tongues sounded hoarse. The fox led them down a gully near Rose Glen Road, over a hill above Mill Creek near the rail line that runs along the bank of the Schuylkill River, and they still worked east-ward. The line crossed the Flat Rock Road, and in the distance the Field could see the old stonewalled mills and brick stacks of Manayunk across the river. Again scent failed. This time it was a herd of dairy cows that the fox used to hide his own perfume. Again a farmer set them right and again the pack owned the line. Going up the steep slope to Mary Waters Ford Road a rider spied the fox and bellowed, “Yonder he goes!” Charles James Fox was no longer loping. He was jogging wearily. Hounds, too, were moving with wearied spirit. The fox's tongue dangled far from his muzzle, as did those of his pursuers. All was now in slow motion. Just before dusk they were closing in on him, and it seemed they might kill unless the staff intervened, but along Belmont Avenue he squeezed through the cast iron palings of the fence around West Laurel Hill Cemetery. Hounds could not get through and the gates were a distance away. Billy Wilson blew a great blast on his horn and called Jack Pechin. “Whip off now lad. These dead Philadelphia aristocrats wouldn't want such a gallant fox killed over their graves, nor would they want us Chester County farmers galloping over them. Let's call it a day—a great glorious day.” Of some thirty riders who had met at Cressbrook, seven were left with the Master, huntsman, and whipper-in. More than a dozen strangers were there. Here, almost at City Line and above the smoke stacks of the Pencoyd Iron Works, the hunt ended. Jack dismounted, cheered his hounds, and blew the traditional “Gone to Earth” on his horn to let everyone know that this had been a great run! Among the newer riders were neighbors who offered hospitality of stable and table. Jack suggested hacking the pack back to King of Prussia, but Billy would have none of that. Several C.V.H. riders accepted over-night stabling and, happily, some Thanksgiving cheer and food. An estate owner took Billy, his staff and pack with him. Billy joined the host family before a log fire and at dinner, while the stud groom entertained the hunt staff. Then the host announced that he had a pair of coach horses hitched to a farm wagon filled with deep straw. Into this they tenderly lifted 13½ couples of exhausted American hounds. Jack promised to return the wagon the following day when he and the whipper-in would ride and lead the three hunters back to King of Prussia. Then on a brisk, but fine moonlight night, Master, huntsman and whipper-in, in borrowed overcoats, sat on the box of an elegant wagon with candle lamps, and drove out the Montgomery Pike, with hounds asleep behind them. In about two and a half hours they were home. The next morning at about half past nine Billy Wilson's telephone jangled and he answered sleepily. It was the foreman at the quarries at Howellville. “Mr. Wilson,” he shouted, “that same dog fox is a-sunnin' himself on the coal pile again. I guess you didn't run him very far yesterday.” Presented at the February 29, 2004 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club.

|