|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Summer 2004 Volume 41 Number 3, Pages 75–84 WATER AND FIRE The Rise and Fall of Valley Forge Industry Hint for using the footnote reference links: Using the “Back” feature of your browser will return to the previous [Note] link location after you read the footnote. The Delete (Mac OS) or Back Space (Windows) keys often perform this function.

This paper discusses the factors behind the development of Valley Forge as an industrial area, focusing on the useful and, to a lesser extent, the destructive power of water and fire. A brief history of Valley Forge industry is also given. Industry first developed in the pre-revolutionary era. This development was halted by the destruction of the British raid of the 19th of September 1777. After the encampment the industry went through a period of recovery leading to the expansion of Valley Forge village to support a sequence of industrial concerns in the 19th century. The industries faltered at the end of the 19th century, never to recover.

The name Valley Forge is very familiar. But why were forges built at Valley Forge? And why is there a valley going through the hills? The answers to these two questions are related. About 500 million years ago the edge of the North American continent was to the north and west of its present location. Off shore was a large sand-bank or perhaps a barrier island similar to those down the Atlantic coast at the present time. Over time this sand was converted into rock (sand-stone). Later it was further heated and pressured and was metamorphosed into quartzite. This is the rock that forms the North Valley hills, including Mount Misery and Mount Joy. 450 million years ago there was another sea in the area where multitudinous small sea creatures died and left their minute shells. These remains were solidified into a type of limestone called dolomite. This rock is softer than the quartzite and underlies the Great Valley. Valley Creek has a strange course. For the upper part of its length it flows northeast down the Great Valley. It then makes a sharp turn and flows through the North Valley hills in a narrow gorge between Mount Joy and Mount Misery. Geologists have proposed a reason for this change in direction. [Note 1] River gravels have been found between Wayne's Woods in Valley Forge National Historical Park and the Pennsylvania Turnpike. This suggests that at one time Valley Creek continued on its northeastern course until it met the Schuylkill River. It has been proposed that there are a series of faults between Mount Misery and Mount Joy. These faults weakened the quartzite rock and allowed a stream to erode its head between the Mounts. When the head of this stream met the ancient Valley Creek, it "captured" the Creek since its bed dropped more steeply. The original course of the lower part of Valley Creek was then abandoned. One of the outcomes of this capture is that Valley Creek drops substantially over a short distance, 30 feet between the covered bridge and the Schuylkill River. [Note 2] This fall of water could be converted into power for industry.

A furnace produced cast iron from iron ore. Cast iron is brittle, due to inclusions of slag and a high carbon content. A forge converted the cast iron to wrought iron by heating, hammering, and stretching. The wrought iron was not brittle - instead it was malleable and ductile - and iron goods could be manufactured from it. The resources required to run a forge were cast iron, power, and heat. At that time the only source of heat available that was hot enough to be used to melt the iron was charcoal. Even a simple charcoal fire was not hot enough. Air had to be blown through it to get to the required temperature. In order to run a forge on an industrial scale, power was necessary to both run the bellows to provide the air supply, and to power the hammer. How was such machinery powered in the 18th century, aside from animal or human power? The first efficient steam engine was not invented until 1776 - by James Watt in England - so that was not an option. Other possibilities were wind or water. There is no reliable wind in this area, so water power was the only possibility. As described above, Valley Creek is a reliable supply of water with a good fall. A furnace reduced iron ore to metallic iron, which was cast either into bars for further processing or into products such as stove plates. Chemically, the iron ore - usually a form of iron oxide - reacts with carbon in the charcoal to produce iron and carbon monoxide and dioxide, which escape as flue gases. The molten iron then flowed to the bottom of the furnace. Limestone was also added as a flux. It reacted with the siliceous parts of the ore to produce a slag that melted at a lower temperature and was light in weight. This slag floated on top of the molten iron and could be skimmed off. Once a sufficient quantity of iron accumulated, it was run into molds of sand and allowed to cool. Furnaces require higher temperatures than forges since the iron needs to be completely molten rather than just soft. The iron makers would fill a furnace with charcoal, light it, and allow it to burn for 5 days to get it hot enough. Only then would they add the limestone and the iron ore. It took about 8 hours to reduce a batch of iron ore to iron. A furnace was run as a 24-hours-a-day operation and the process used a lot of charcoal. In fact it is estimated that a furnace used an equivalent of an acre of wood every day it was running to produce this charcoal. [Note 3] The "blast," as the operation of the furnace was called, continued for as long as possible - sometimes for many months - and there are even examples of blasts lasting over a year. [Note 4] One year Warwick Furnace used charcoal equivalent to 240 acres of wood in its operation. [Note 5] Once trees had been cut to make charcoal, the logged area would have to be left for new trees to grow up again. The best trees for making charcoal are around 30 years old. [Note 6] In other words, you had to have enough land to leave it for 30 years for the trees to grow again. Multiplying these factors means you need about 7000 acres of woodland to run a furnace in a sustainable way.

Other authors have suggested that a lack of local iron ore, or its poor quality, were the reasons for there being no furnace at Valley Forge. But local ore was used in a furnace in the Valley Forge Park area at Port Kennedy in the second half of the 19th century: A number of iron ore mines were operated in Tredyffrin prior to 1854 ... and Samuel Beaver's ore pocket near the foot of the North Valley Hills about a mile southeast of the head of the Valley Forge dam was also of considerable size, and there were large pockets of excellent brown ore mined west of the Valley Creek on the southern slope of the North Valley Hills, most of which was smelted in Phoenixville. Indeed this range of hills is pocketed with old mines. [Note 7] The problem at Valley Forge was that, unlike places like Warwick and Hopewell Furnaces, there was significant farming in the Valley Forge area when the first forges were established. There was not enough woodland for the iron masters to acquire to make charcoal. The maximum they managed to acquire around Valley Forge was about 1000 acres. It is therefore the lack of sufficient quantities of wood that constrained the operations at Valley Forge to that of a forge.

Charcoal was still needed to run a forge, but in lesser quantities than to run a furnace. In 1759-1760 the Valley Forge used 400 wagonloads of charcoal. [Note 8] This was also the amount taken or destroyed by the British in their raid of 1777. [Note 9] The person in charge of making charcoal was the collier. A flat section of land about 30 feet across, called a platform, was needed for the production of charcoal. Often the platform would have to be cut into a hillside to produce the necessary flat area of land. You can find 15 of these charcoal platforms on Mount Misery. The wood to be converted into charcoal was stacked compactly around a central chimney, covered with leaves and earth, and set alight. In order that all the wood would be converted to charcoal, the pile needed to smolder, not burn, for 10 to 14 days. During the smoldering, the colliers had to ensure that fire did not break out in the piles. One of the techniques used to reduce the chance of fire was to climb on top of the piles and stamp them down to eliminate air pockets. The colliers needed to be close at hand while the piles were smoldering in order to damp down any fires as soon as they broke out. So they built small huts near the platforms from which they could constantly observe the piles. The colliers lived in these huts while the charcoal production was taking place. A hut was a little wigwam of wood. A circular trench of about 12 feet in diameter was cut and the excavated dirt was piled into the center. Tree branches and small trunks were then stacked with their bottoms in the trench. Earth and leaves were used as fill in between the boughs. The raised center ensured that the occupants could not be flooded out.

A model collier's hut at Hopewell Furnace. The characteristic remains of a collier's hut are a circular ditch with a mound in the center. There are many of these remains in French Creek State Park and Hopewell Furnace. The remains of two huts have been found on Mount Misery. The forge proprietors owned different areas of woodland along the ridges of Mount Joy and Mount Misery that added up to the 1000 or so acres mentioned above. There is no sign of any charcoal making on Mount Joy. The reason for this is unclear. The other areas owned by the iron masters around Valley Forge are on private land, so searching for charcoal platforms is not possible. It is not clear whether there are remains of platforms or huts on these plots of land.

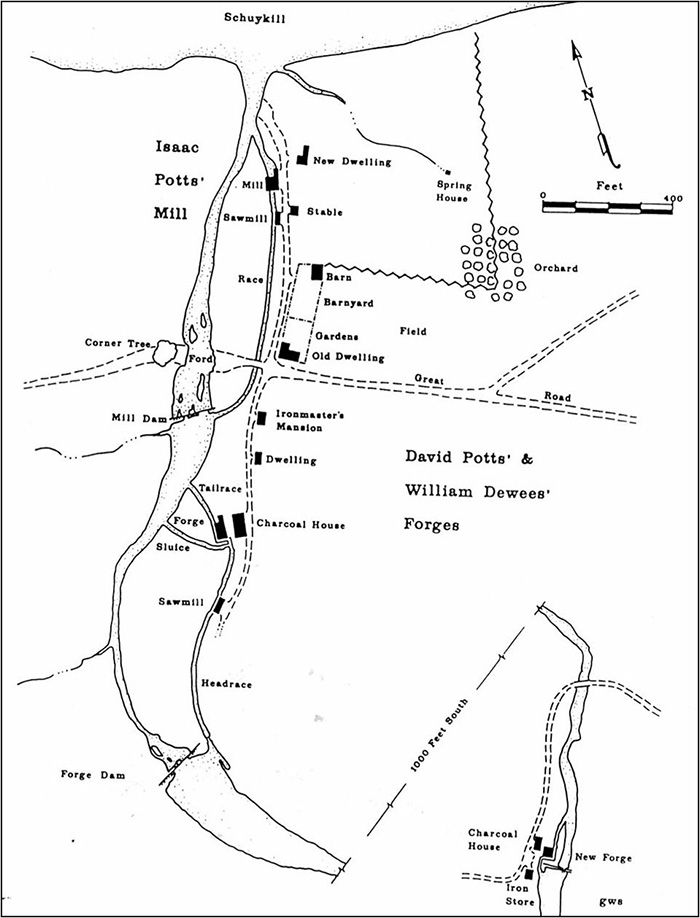

The history of the forges before 1777 is described in detail by Garry Stone. [Note 10] Readers interested in further details and references should consult this article. Although there are suggestions of an earlier forge, the first documented forge was built by Stephen Evans and Daniel Walker, who purchased a plot of land from William Pen's attorneys in 1742. The forge was established in 1742 or 1743 - based on an increase in taxable value - on the east side of Valley Creek. Evans and Walker unsuccessfully tried to sell the forge and related sawmill in 1751. Then in 1757 the operation was acquired by John Potts, the famous iron master. He developed the forge and a grist mill and each operation used a separate dam. The grist mill was further down Valley Creek, close to the Schuylkill River. In 1764 Potts tried to sell the grist mill and ran the following advertisement: To be SOLD or LETT, A Valuable Merchant Mill, situate in Philadelphia County, on the River Schuylkill, about 20 miles from Philadelphia, on Valley Creek, known by the name of Mount Joy Mill, three Stories high, built of Stone, with two pair of Stones, and two Water Wheels within the House, double geared, three Boulting Chests, hoisting gears, and every necessary Convenience for making Flour, with a Canoe house at one End of the Mill, where any Quantity of Wheat may be purchased and unloaded very handily in Times of Freshes, the Mill is large enough to hold above 10,000 Bushels of Wheat. Also an Exceedily good Saw Mill, close by the said Mill, on the same Race, the Stream of Water never fails in the dryest Seasons, and never freezes in the severest frosts. For Terms apply to JOHN POTTS, at Pottsgrove, or to Samuel Potts, on the Premises; it may be entered on the first of October next, or sooner. [Note 11] Substantial information is known about the operation of the forge as daybooks exist for several years of operation. The cast iron for the forge was transported from Warwick Furnace. In one year the forge produced 110 tons of wrought iron. The iron cost about £20 per ton to make and sold in Philadelphia for £25-£32 per ton. The forge employed 25 full time people as well as part time people. Typical salaries were £100 per year for a manager, £80 for skilled ironworkers, £40 for millers and blacksmiths, £20 for teamsters. Some of the work was piecework: a cooper was paid 9 pence for each cask and colliers were paid 11 shillings and 5 pence per wagonload of coal (charcoal). In 1773 the forge was acquired by David Potts and William Dewees. Dewees was related to the Potts family by marriage. He managed the operation at Valley Forge, while David Potts sold the products of the forge from a store in Philadelphia. In 1775 William Dewees built a second forge, known as the upper forge, and its associated dam further upstream along Valley Creek. This forge was on the west side of the Creek in Tredyffrin Township. There are at least 4 maps showing the Valley Forge area in 1777-1778. A Duportail map gives the greatest detail and shows both the lower and upper forges and associated buildings. This map was found in the quarters of the French engineer, General Louis Duportail, during a refurbishment of the building and is now at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. The second map is drawn by Garry Stone and is based on the Duportail map. It is shown on the next page. Interestingly, this map does not show any road connecting the two forges on Valley Creek. It does show a road with a west end on Mount Misery that descends to the upper forge, then fords Valley Creek, and climbs Mount Joy, where it divides. A trail exists today down from Mount Misery to the site of the upper forge. Remains of the road on Mount Joy can also still be seen. A British map from September 1777, corroborates the Duportail map in the area of Valley Forge village, but it has a blank area where the upper forge was located. It does show the two roads at the top of Mount Joy. The history of this map is unclear. Another French engineer made the fourth map, focusing on the defenses and roads, but showing little detail of the buildings.

William Dewees was a colonel in the militia, and his lower forge, nearer the Schuylkill River, was selected as a storehouse for the Continental Army. Dewees worried that this would attract the British Army - as indeed it did - but after protesting, he agreed to take care of the stores. After the Battle of Brandywine on the 11th of September, Washington retreated across the Schuylkill River to Philadelphia. When the British did not advance, he re-crossed the Schuylkill and set a line of defense on the South Valley hills. On September 16th the armies engaged in what is known as the Battle of the Clouds. As the battle commenced, a northeasterner blew in and it began to rain hard. The gunpowder got wet in the driving rain and the muskets and guns were useless. It was also difficult to see the enemy. Washington decided to retreat to Yellow Springs to dry out. After further evaluating the situation, he decided to retreat further to Reading to get dry supplies. [Note 12]

Reconstruction by Garry Wheeler Stone showing both the lower and upper forges and their associated buildings around 1775. The original, lower forge is near the center of the map. The new, upper forge is on the extension of the map in the lower right corner. This meant Valley Forge was undefended. The British made a move to take the supplies on the 19th of September. Although Dewees and others managed to get some of the supplies across the Schuylkill to safety, most of them were captured by the British. The haul was "upwards of 3800 barrels of flour, soap, and candles, 25 barrels of Horse Shoes, several thousand tomahawks and kettles, and intrenching tools, and 20 hogshead of resin." [Note 13] As they left, the British destroyed both forges and their associated dams.

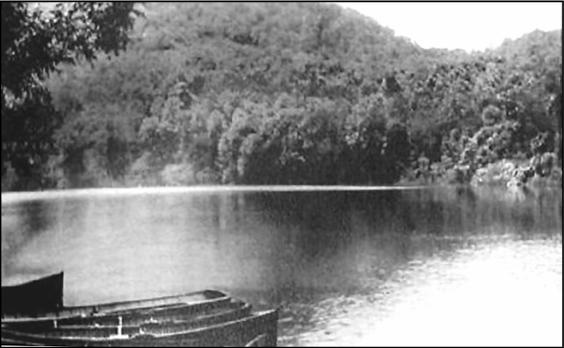

In the 1780s a new dam was built just upstream from the present Route 23 bridge over Valley Creek. The dam created a large mill pond that stretched as far as the covered bridge on Yellow Springs Road and submerged the upper forge. In the 1920s Valley Forge State Park expanded its boundaries around the lower part of Valley Creek and Washington's Headquarters. They wanted to make the area look as similar as possible to the way it had been at the time of the encampment. Buildings were razed and the main dam on Valley Creek was demolished - after many protests - in 1920 [Note 14] draining the mill pond. The removal of the mill pond uncovered the site of the upper forge, further up Valley Creek. The present dam on Valley Creek, 1,000 feet south of the Route 23 bridge over the Creek, dates from this time. Its position is where the original lower forge dam - destroyed in 1777 - was located.

The mill pond created by the dam built in the 1780s was large enough to go boating on. In surveying the new park land the old upper forge was discovered under 7 feet of silt. A three year excavation, starting in 1929, uncovered substantial remnants, including the remains of the walls, bellow and hammer foundations, water wheels, and raceways. [Note 15] Many of the timbers had been burnt. What was the upper forge used for? Was it used only to enhance the capacity for the existing business, or for some other use? The evidence suggests some other use. First, the lack of a road between the two forges is suspicious. And why were there only obscure roads to the upper forge? Without any obvious roads, the forge must have been well hidden. The site is not observable from either end of the gorge between Mount Joy and Mount Misery. The facts fit the proposition that William Dewees used the forge to make armaments for the Continental Army. The remains included half a cannonball mold and a cannonball. Some of the metal artifacts were analyzed and have compositions similar to that of steel, which suggests that steel-making may also have been taking place.

The grist mill and its dam close to the Schuylkill River had not been destroyed by the British raid. Around 1789 a new forge and dam were built to replace the destroyed lower forge and dam. This dam had a large fall of 17 feet. [Note 16] In addition to the mill stream that powered the forge on the Montgomery County, or east, side of Valley Creek, there was a second mill stream on the Chester County, or west, side. This second mill stream initially powered a rolling and slitting mill. These three operations changed over time, and together with a later shoddy mill built in 1867, constituted the basis for Valley Forge industry in the 19th century. Harold Twiss describes in detail the rise and decline of the village in that time period. [Note 17]

The development of transportation in the 19th century most certainly improved the economics of Valley Forge industry, although it is difficult to point to specific facts and trends. Improved transportation would have reduced both the cost of importing raw materials and the cost of getting products to market. The first improvement in transportation was on the Schuylkill River. This was called the Schuylkill Navigation and was opened in 1824. [Note 18] It was a series of dams across the river, which provided greater, and more consistent, water depth for the boats, thereby improving the movement of goods. Each dam had locks, through which the boats could pass. It is often referred to as the Schuylkill Canal, which is not strictly correct, since sections of canals were built only in places where it was necessary. Valley Forge was between the Catfish Dam, downstream of the Betzwood area, and the Pawlings Dam, just below the present Pawlings bridge further upstream. Catfish Dam had a height of nearly 5 feet.

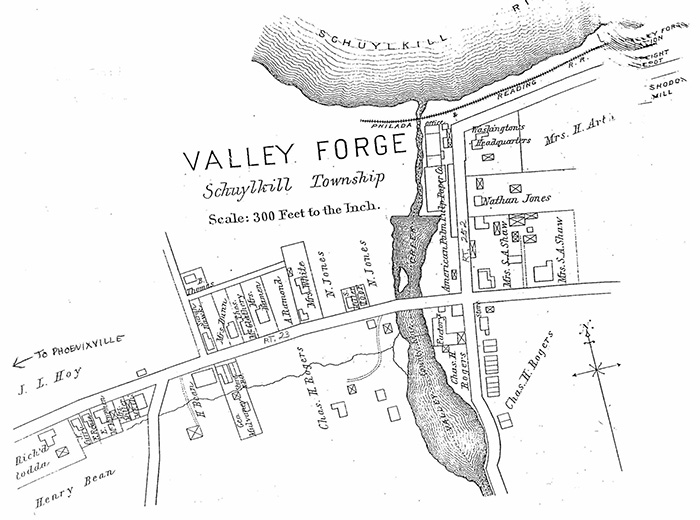

Valley Forge Village around 1883. Route numbers 23 and 252 and the arrow to Phoenixville do not appear on the original map. The Schuylkill Navigation was not in operation long before competition appeared in the form of the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad. This opened in 1838 with stations at Valley Creek and Port Kennedy. There was also a goods depot at Valley Forge. This line was built early enough in the development of the railroads that iron rails could not be obtained in the United Sates and were instead imported from England. [Note 19] The improvement in transportation drastically enhanced the availability of coal. By 1830 coal was being advertised by local coal merchants. [Note 20] Despite the availability of coal, water power was still used in Valley Forge throughout the century until the end of industrial operations.

The rolling and slitting mill was built before 1790 and consisted of a 30 x 80-foot stone building where bars of wrought iron were rolled into sheets and then slit into strips used to make nails and other products. John Rogers and Joshua Malin purchased the mill and associated lands in 1814. In 1818 it is said that a large stack and 6 furnaces were erected between the rolling mill and a nearby smith shop, and that cast steel was manufactured there for use in the production of saws. [Note 21] This may be the first example of U.S. cast steel. Unfortunately, there only seems to be secondary accounts of this enterprise. In 1821 the building was converted into a gun factory. Two stories were added to the building to support the new operation. John Rogers, who owned the building, and Brook Evans made about 20,000 muskets on contract to the U.S. government. It is not clear whether all or only part of the manufacturing process took place at Valley Forge. [Note 22] The tax records show that the factory was idled in 1834. In 1841, due to financial problems, the gun factory was put up for sale by the Sheriff as a part of the whole Valley Forge operation.

The old grist mill continued to operate until it was burned by a spark from the railroad in 1842 or 1843. It was rebuilt slightly further up Valley Creek. Isaiah Knauer, who previously had been running an agricultural implements business at Valley Forge, purchased the mill and turned it into paper factory in 1869. [Note 23] It was then leased to various concerns and was used to make envelope paper, card middling, bank notes from palm leaf, and parchment paper. The mill was partially burned in 1877, but rebuilt. [Note 24] None of these businesses lasted for a long amount of time, and it was abandoned in the 1890s.

Shoddy is a low quality cloth made from rags. The rags were pulled apart to separate the individual fibers which were then respun and rewoven into cloth. Henry and Andrew Arthur, British industrialists, developed and ran this shoddy mill in Valley Forge. The mill had the same problem that most of the other industries around Valley Forge encountered; it burned down at least twice, in 1872 [Note 25] and in 1873. [Note 26] The mill was to the east of Valley Forge station.

The rebuilt forge operated until 1797 or 1798, when its taxable value dropped from £1000 to £300. [Note 27] This reduction probably reflects the idling of the forge.

This photograph from the Library of Congress American Memories database shows the remains of the Shoddy Mill in Valley Forge at the middle right edge, the Schuylkill River on the left, the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, and the goods depot.

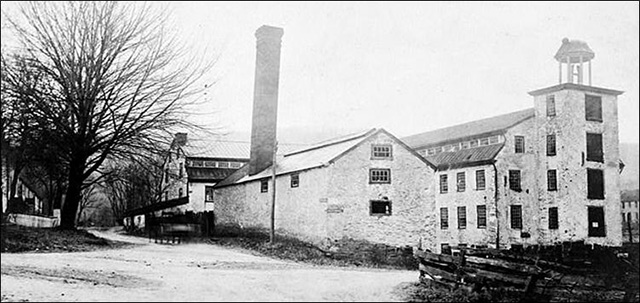

This photograph from the Library of Congress American Memories database shows the Cotton Mill buildings in Valley Forge around 1900. They were located at the southwest corner of the intersection of present day Routes 252 and 23. This view is looking south, with the road that would become Route 252 to the right of the tree on the left. The road that would become Route 23 crosses from left to right across the bottom. The erection of a mill building for the spinning and weaving of cotton was initiated by Joshua Malin when he was in partnership with John Rogers. In 1816 John Rogers acquired sole ownership of the property, [Note 28] and completed a new building in 1820. The mill was unsuccessfully run as a cooperative community for a year. Except for a short period, the property ownership stayed with the Rogers family until after the end of industrial activity. A number of people leased the mill during this time. The mill made cloth such as jean (the material, not the pants), doeskins (a fine, soft, smooth woolen fabric), and government kerseys (woolen worsted for uniforms). When operating at full capacity it employed 100 people. It also burned in 1855 [Note 29] and in 1869, [Note 30] but was rebuilt on each occasion and continued in operation until 1882. Isaac Smith who managed and leased the mill for 20 years, built a new mill - presumably coal powered - in Bridgeport in 1882, and transferred his business to the new site. After that event the mill never reopened and was acquired by Valley Forge State Park in 1919.

Valley Forge is a wonderful example of 18th and 19th century water-powered industry and should be considered a significant part of our industrial heritage. Unfortunately, much of this industrial history has been destroyed. It is a pity that this part of Valley Forge National Historical Park's history does not get more attention. The remaining artifacts should be better displayed and the story of the industrial history of the village told through displays, exhibits, and other means.

Various members of the staff of Valley Forge National Historical Park provided invaluable assistance. The Library of Congress American Memories web site provided documents and photographs. I also obtained substantial help from the staff at the Chester County Archives and the Chester County, Montgomery County, and Phoenixville Historical Societies, and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Mike Bertram is a retired pharmaceutical executive and avid runner who lives adjacent to Mount Misery and has a passion for local history. This was presented at the May 23, 2004 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. It was transcribed by Bonnie Haughey. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||