|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 41 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Fall 2004 Volume 41 Number 4, Pages 119–130 A LOCAL BAND OF BROTHERS The 97th Pennsylvania Infantry During the Civil War

I've put together a program on the 97th Pennsylvania Volunteers, the Chester County regiment. Typically I don't give talks on regiments because, frankly, there's so many of them, I can't keep track of them all. For those of you who are unfamiliar with the Civil War, it is the largest conflict that the United States has ever engaged in. Some of you may remember World War II and say, "I'm not sure that's a true statement about the Civil War." Let me share with you that the Civil War casualties were over 620,000 Americans. WWII casualties were not quite 420,000. The population of the U.S. according to the census of 1860 was about 33,000,000. Another million and a half were injured or wounded in battle. It took a toll on America from which America has never recovered. The Civil War settled two issues for America. It settled the issue of slavery. Before the Civil War, slavery was rampant within the country. Three, almost four, million Americans were held as slaves and one in seven Americans owned another American. When the War was over, slavery was over. There were also people who insisted that secession was the right of the state; to leave the Union if it disagreed with the federal government. Since the war ended, no state has ever again suggested secession as a remedy for federal ills. So it settled two issues. It is the watershed; it is the conflict that defined America. Before the Civil War, people said "...the United States are..." After the war, they said "...the United States is..." When we pledge allegiance to our flag we say, "...one nation, under God, indivisible..." The phrase "under God" comes directly from Lincoln's Gettysburg address. The Civil War established the indivisibility of the country. That's its value to us. The 97th Pennsylvania was part of that country. They were mustered in at Camp Wayne in West Chester, Pa. on 29 October 1861. Actually, when the Confederates fired on Fort Sumter on 12 April 1861 and Fort Sumter surrendered on 14 April 1861, President Lincoln issued a Proclamation and called for 75,000 volunteers. The standing army of the U.S. in April of 1861 was about 5,000 men. Lincoln's call for 75,000 volunteers was for an army larger than fought the Revolution and the War of 1812 and the Mexican War combined. The southern states took that as a declaration of war; that this would become a war of northern aggression. Lincoln's volunteers were only to serve for 90 days and the 49th PA did, in fact, serve for 90 days. After the Battle of Bull Run, which the Union Army lost, most of those 90 day regiments disbanded. The North realized that they were going to have to have regiments that lasted a lot longer. So the 97th PA was established by the Legislature of the Commonwealth, either as a three-year regiment or for the duration, whichever came first. They started their recruiting in August of 1861. They gathered volunteers from all over Chester County and from Delaware County as well.

Governor Andrew Curtin presented to them their flag at the end of October when he officially commissioned the regiment. I brought with me the regimental history of the 97th, which was kindly loaned to me by one of the members of the Brandywine Round Table, Mrs. Florence Williams. I want to read to you exactly what Governor Curtin said [excerpted below]. They met in West Chester at Camp Wayne and he said: Fellow citizens and soldiers: I am here to-day for the performance of an official duty. The Legislature of our State, at its late session, provided that regimental flags should be procured and presented to the brave men who should go out from the State for the defence of the National Government... I cannot stand here to-day without remembering that, in the year 1682, the county of Chester, the proprietors and founders of the province enacted, by and with the consent of the delegates assembled, the first body of laws for the government of Pennsylvania. . . . No general stood more highly in the confidence of the Father of his Country, none did more valiant or better service than Gen. Anthony Wayne... That name, I find, is now inscribed upon the roll of your Regiment and that you have a Wayne as one of your Captains. I am gratified to see, too, that another Revolutionary name has its representatives in your ranks: two lineal descendants of that John Morton, who was a signer of the Declaration of Independence, are lieutenants in another company... Here, too, we are in the vicinity of Brandywine, Paoli and Valley Forge; and here, indeed, we cannot but feel we are treading upon classic ground... Take, then, this flag; upon its blue field is placed the coat of arms of Pennsylvania, surrounded by the thirty-four stars emblematic of the States of the whole Union... Upon its return, it will have inscribed upon it the record of those battles through which you have carried it, and will become a part of the archives of Pennsylvania; and there it will remain, through all time... I entrust it to your care and for the last time bid you farewell. 1 With those words, Governor Curtin presented to the 97th their battle flag and commissioned them the 97th Volunteer Infantry.

Civil War soldiers' training, unlike today's soldiers' training, was brief. They were issued a manual of arms which they got to read, and they were taught how to march and how to drill. The reason they were taught to march and drill was that they would march in columns of four in long lines but when they would array for battle, they would turn and array shoulder to shoulder in line of battle, three ranks deep. To get them to go from line of march to line of battle was an extremely difficult thing, first for the soldiers and then for the officers. The officers had little or no training because most of them had no formal military experience. In addition to that, they had to learn to load, carry, clean, and care for a weapon. Their weapon was an 1861 Springfield muzzle-loading musket, which fired a .69 caliber ball at 300 feet-per-second when it left the muzzle. To load a muzzle-loading musket, even though it had a percussion cap on it, took eleven separate operations. A practiced soldier during the Civil War, after he got the hang of it, could get off about three rounds a minute. The accuracy of the weapon was about 300 yards. It had a range of about one-half a mile but could effectively kill people at 300 yards. During the Revolution, those muskets had a range of about 50 yards. When Revolutionary War muskets discharged, the defenders would discharge one round, which would go out about 50 yards. It might kill someone, or it might not. Then it was an all out charge against the defensive position and the advantage was with the attackers. During the Civil War, exactly the opposite was true. Because the musket had a range of 300 yards, the defenders could get off three rounds before the advancing party was upon them. That's why when Pickett's Charge stepped off at Gettysburg, although 12,000 men started out, only 4,000 men came back. Were they a well-trained and fighting regiment? The soldiers of the Civil War learned quickly how to camp. Do you think that would be a fairly simple thing to do for people who had lived in town all their lives—to sleep outside in all kinds of weather, with no provisions for shelter? Did they have tents? Yes. Their tents were open at both ends. It was just a piece of canvas strung over a pole. They slept on the ground. They had no bivey sacks, they had no sleeping bags. They were issued one blanket each and they wore a wool uniform. Did it keep them warm? Not very. The regiment lasted four years, even though they were a three-year regiment. They were not mustered out until 4 September 1865. They finally returned their battle flag as Governor Curtin asked them to do at Independence Hall on 4 July 1866.

The 97th PA companies included the:

Every regiment had a band. I played some music today from the 97th PA regiment string band. Is it original? No. It's a reenactment and they don't even play period instruments. They play guitars and mandolins and banjos, independent company, and, of course, headquarters company. During its lifetime the 97th had 3 commanding officers. Henry R. Guss was the commanding officer from 1861 to 1864. He resigned his commission in May of 1864. Exactly why he did is not clear. He was replaced by the Lt. Colonel of the regiment, Galusha Pennypacker, a Captain who had been with the 47th PA, had been promoted to Major when they left Chester County, and took over as commander of the regiment. Pennypacker commanded the regiment for less than a year. He was replaced by Lt. John Wainwright, who commanded the regiment from 1864 to 1865.

These are the battles in which the 97th PA was engaged in which they incurred casualties:

Of the 2004 enrolled, the casualties they incurred during the war included:

You'll notice there are more who died from disease than died from battle wounds. Disease killed more Civil War soldiers than enemy bullets. To give you an idea of casualties, about 6% of soldiers in the Civil War who were killed were killed by artillery fire. About 2% of those killed were killed by bladed weapons, that is, bayonets or sabers. All the rest were killed by musket fire. Of the ones who died of disease, there were about 620 casualties. About 380,000 of those who died, died of disease—measles, mumps, chicken pox, pneumonia, gangrene. There wasn't a soldier who served in an army on either side who did not have a continuous case of amoebic dysentery all the time they were in the army. They knew nothing about sanitation. They didn't know anything about germs. They didn't know how to purify their water. Bruce Catton, the famous Civil War historian referred to the Army of the Potomac as the "coffee boilers." Whenever they stopped, the first thing they'd do is get their fires started, grind the coffee beans that had been issued to them, and boil their coffee beans. Because the Army of the Potomac drank so much coffee, it saved the lives of many, many men—not because the coffee was any good, but because they boiled the water.

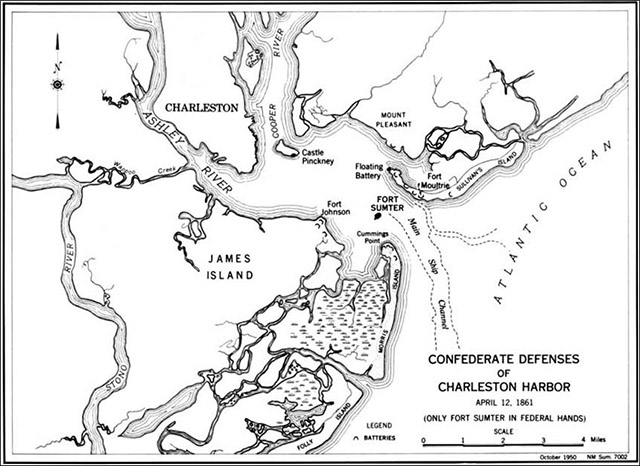

The first battle we're going to talk about is the battle of Morris Island. James Island, Morris Island, and Fort Moultrie are all in the Charleston Harbor area and out in the middle of the harbor is Fort Sumter.

It was at Fort Sumter that the Confederates fired the first shots that started the Civil War in April of 1861. Battery Wagner was on what is now Morris Island. Today it is little more than a sand bar and has changed much since the Civil War due to tides, winds, and hurricanes. From 1861 to 1865, the U.S. Navy tried to capture Charleston Harbor, without success. This effort was made in the summer of 1863. While many were up in Pennsylvania fighting the Battle of Gettysburg, these people were at Charleston Harbor trying to capture Battery Wagner. The most famous regiment to assault Battery Wagner was the 54th Massachusetts. You may have seen the film Glory with Denzel Washington and Morgan Freeman. That is the story of the 54th MA. Right behind the 54th MA in their assault on Battery Wagner was the 97th PA.

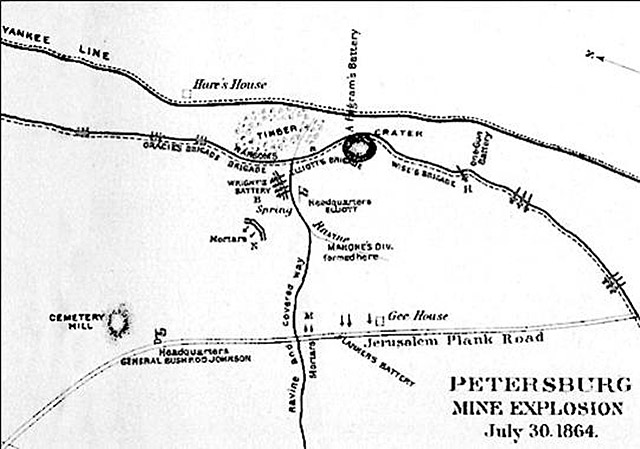

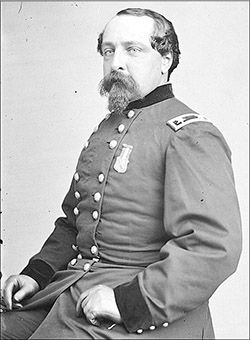

Edward Ferrero The Battle of the Crater took place during the siege at Petersburg. The Army of the Potomac had been commanded by Irvin McDowell, replaced by George McClellan, who was supplanted by John Pope, but then McClellan again, then Ambrose E. Burnside, then Joseph Hooker, and finally, just before the Battle of Gettysburg, the last commander of the Army of the Potomac was George G. Meade. The Army of the Potomac, other than at the Battle of Gettysburg, had little or no success against Robert E. Lee. When Grant came east, he was given command of all the armies of the whole U.S. He made his headquarters in the field of the Army of the Potomac and the overland campaign began in the wilderness of May of 1864 and they pushed Lee from the wilderness to Spotsylvania; to Cold Harbor. Grant crossed the James River and tried to get between Lee and his supply lines by investing of Petersburg, just south of Richmond, during this period of time. Once they got to Petersburg, it became a siege. The 97th PA was assigned to the second division of the 9th Corps, commanded by General Ambrose Edward Burnside. Burnside had been commander of the Army of the Potomac. Ulysses S. Grant was, by this time, Lt. General and commanded all the armies of the U.S. The Army of the Potomac was commanded by Pennsylvania's own George Gordon Meade. The second division of the 9th Corps was commanded by a man named Ferrero and the first division of the 9th Corps was commanded by a man named Ledlie. The mission of the 9th was to dig a trench—a tunnel—underneath the Confederate lines, pack it full of powder, explode it in the middle of the night, and blow a huge hole in the Confederate lines. The 9th Corps would then rush through and break the siege at Petersburg. That was the plan. The line was constructed by the 48th PA from nearby Schuylkill County. Lt. Colonel Henry Pleasants, who before the war had been a mining engineer, went to his commanding officer, a man named Robert B. Potter. Major General Potter was a good friend of General Burnside and Potter took it to Burnside. He said, "These people want to dig a mine underneath the Confederate lines and explode it and break the siege at Petersburg. What do you think?" Burnside says, "Can they do it?" Potter says, "They say they can." Burnside said, "Let's do it, then." He took the idea to General Meade, who thought it was a bad idea. Meade said, "That's foolishness. Nobody can possibly do that." But Burnside insisted, so Meade decided to take it on to General Grant.

Grant had no experience with such mines at the siege at Vicksburg in July of 1863 but he said, "If they think they can do it, let them try." So they did. They began about the 15th of June 1864 digging the tunnel. The tunnel for the mine was about 500 feet long and was about 35 to 40 feet underground. These Pennsylvania miners from Schuylkill County dug the whole thing. The Confederates could hear digging but they didn't know where it was. They even tried to put probes down in the ground to find them but they could not find them. They lengthened the tunnel. They built the gallery and they loaded it with about 7,000 pounds of black powder while the 48th PA dug the mine. The idea was for the second division to spearhead the attack once the explosion took place. Now, it just so happens, that in Ferrero's division, in the 2nd Division, in addition to the 97th PA, was the 28th and 29th U.S. Colored Troops. Two days before this mine was supposed to explode, General Meade went to General Burnside and he said, "Give me your battle plans." Burnside explained about the tunnel and the mine and the explosion and that these colored troops would go in and divide, spread around the mine, and march past the crater, capturing the Confederate lines. Meade said, "You can't have the colored troops do that." Burnside said, "They're the only ones that are trained to do it. Everyone else has been heavily engaged in battle. I have no other troops." Meade said, "You can't do it. If those people get injured or it turns into a disaster, they'll blame us for using these colored troops as cannon fodder. We've got to change it." Burnside insisted. Meade said, "All right. We'll take it to General Grant and he'll make the decision." They went to General Grant. Grant, half paying attention, said, "Whatever Meade said is what we'll do."

James Hewett Ledlie Meade ordered Burnside to chose another company for the assault. He chose to go back to the Corps and gave the other division commanders the opportunity to draw straws. He didn't appoint anybody; he just said, "Whoever draws the short straw, leads the attack." It was drawn by James H. Ledlie. Ledlie had been a civil engineer before the war but he'd never commanded troops in battle before. He had less than 18 hours to train his men in what to do when the mine exploded. The mine explosion was supposed to go off at 3:30 A.M. They lit the fuse, which was nothing more than a small trench filled with black powder, and waited. And waited. Nothing happened. You've seen small boys who light a firecracker, throw it on the driveway and wait and nothing happens. Every mother says to her son, "Don't touch it." Well, Henry Rees, Sergeant of the 48th PA, had that same experience. He said, "There's something wrong with the fuse." So he volunteered to go into the tunnel to find out. He went into the tunnel about 100 feet and found that the trench full of black powder had burned out, so he relit the fuse and as the fuse burned away, Henry Rees ran for his life in the other direction. He got just to the mouth of the tunnel, when it exploded at 5:30 A.M. Seven thousand pounds of black powder blew Confederates, cannons, horses, trees, dirt, rock, everything, hundreds of feet into the air. The crater that was left was 138 feet long, 68 feet wide, and 40 feet deep. The 1st Division drew forward without proper training. They didn't know that when they got to the rim of the crater they should divide. So they went into the crater. When they got into the crater, they found that they couldn't get out because of the soft dirt and steep walls. When they climbed up, they would slide back down. The Confederates recovered. They marshaled their troops, led by General Billy Mahone. They came to the rim and shot the Yankees in the crater. Fish in a barrel. When Ferrero's 2nd Division was sent forward, the colored troops were left in the rear and it was the 97th and others who, finally, in conjunction, brought order out of chaos and rescued the rest of the men who were in the crater. As you might imagine, a Court of Inquiry was convened to find out exactly what happened. It was chaired by Pennsylvania's own William Field Scott Hancock from Norristown. Hancock took testimony. They investigated. General Grant gave testimony. So did Meade and Burnside. Burnside's testimony indicated that General Meade had overruled the use of the U.S. Colored Troops to spearhead the attack of the crater. Well, the Court of Inquiry, not interested in pinning the blame for the failure on the commanding general, chose a different scapegoat. They blamed Burnside. In addition, there was a surgeon from the 29th Michigan who testified in front of Hancock's commission that Ledlie was with him and a bomb crew in a bomb proof—a safe bunker dug underground—about 50 yards behind the regimental headquarters of the 9th Corps. They asked the surgeon what he was doing. He answered, "Tending the wounded." They asked, "What was Ledlie doing?" He said, "Sitting there." They asked, "Was he not in command of his troops?" He said, "He would issue orders from time to time, write them out, and give them to couriers." They asked, "Was there anyone else in there?" He said, "Yes, Ferrero was with him." They asked, "Both of them were in there?" He said, "Yes." They asked, "How long were they there?" The surgeon replied, "For the whole battle." It was confirmed by another surgeon from another Michigan regiment, the 20th MI. The 20th MI surgeon indicated to the commission that while Ferrero and Ledlie were in the bomb proof, they asked for stimulants. The commission asked, "Did you give them any stimulants?" He said, "Yes." They asked, "What did you give them?" He said, "Rum." So these two generals who were supposed to command the attack of the crater sat in this bomb proof drinking rum while their regiments advanced. The disaster of the crater cost Burnside his job. He wasn't fired, nor was he relieved of his command, but General Grant sent him back to Rhode Island and told him to stay there until further orders came. They still have yet to arrive.

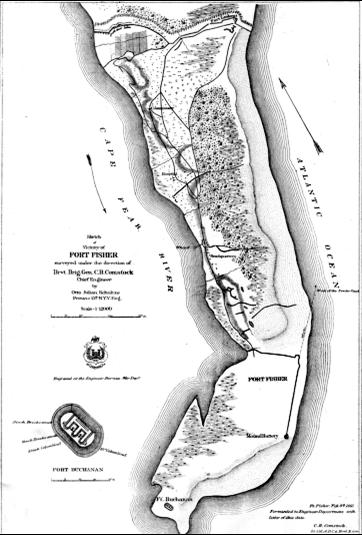

The last engagement we're going to talk about with respect to the 97th PA has to do with the capture of Fort Fisher, North Carolina. It is at the mouth of the Cape Fear River about seventeen miles south of Wilmington, North Carolina. The Cape Fear River flows from Wilmington out into the Atlantic Ocean. Right at the tip of the peninsula is Fort Fisher. The Confederates had mined the river with Confederate torpedoes. This is an actual torpedo that was in the river at the time—a big one of about 250 pounds. They were filled with black powder and fused with fulminated mercury fuses, some with friction primers. These small ones were mounted on the ends of 2 x 4s—long stakes—and anchored at the bottom of the river. When ships would come along, they would bump into the tops of the torpedoes. The torpedoes would explode and sink the ships. The Confederates, because they had little or no navy, relied on such devices throughout their entire history. One of the members of the Brandywine Valley Civil War Round Table became so interested in Confederate torpedoes, he has written a book about it and has become the national expert on Confederate underwater torpedoes. Before the invasion, the U.S. Navy started to bombard Fort Fisher and the peninsula and they put over 40,000 rounds of ordinance onto that peninsula. We visited a man last January who lives not far from Fort Fisher and his hobby is to dig up and collect old union shells. He has three different kinds of metal detectors. He has a collection in his living room, which is as wide as this room, of different examples of navy ordinance that he's dug up out of the sand. He says they are live and full of black powder. He drills them out. He keeps the powder wet with water. We went out into his workshop and he had a three pound coffee can two-thirds full of black powder that he had taken to some his union shows (?) My friend actually exploded some 139-year-old black powder last January with two electrodes at the end of a cable and a magneto generator. The next time we go there, Jay may not be there.

This was the largest single naval bombardment in the history of the U.S. prior to WWII. Forty thousand rounds onto the peninsula. Who was in command? This was the 10th corps of the U.S. Army, (I want to say the Army of the Potomac) under the Army of the James (I'm not sure of that). The commanding officer was a man named Alfred Terry, who later gained fame as the commanding officer of the war against the Plains Indians after the Civil War. He was the man who commanded the 7th Cavalry and Custer. He commanded John Gibbon and George Custer and that whole operation out there during the Civil War. Underneath Terry, commanding the division in which the 97th was involved, was Adelbert Ames, a graduate of West Point. He had started the Civil War in command of the 20th Maine. The 20th ME gained its fame and reputation in the defense of Little Round Top at the Battle of Gettysburg. Adelbert Ames commanded the 20th ME until four days before the Battle of Gettysburg, when he was promoted to division command. He was actually on the north end of the battlefield at the Battle of Gettysburg when his protege, Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain fought the famous battle of Little Round Top. Adelbert Ames is in command of the 2nd Division in which the 97th finds itself fighting at Fort Fisher. Fort Fisher had parapets and in between each of these mounds were mounted twelve pounder and thirty pounder Rodmans. They were called thirty pounders because they'd hurl a shell that weighed thirty pounds and would explode in the air above the troops. It was fused and it was an exploding shell. It was fired up just above the troops and was designed to explode and throw fragmentary metal in all directions. The 97th PA was right in the middle of the line of battle that charged Fort Fisher. The Confederates are on top of the parapets, defending. When the 97th charged, they came down and swept around to what would be the left side of the Confederate fort. They charged up. Galusha Pennypacker is now in charge of the brigade which included the 97th PA; he's no longer in charge of just the 97th PA. Pennypacker saw the 97th's colors on top of the parapet begin to fall. He rushed over, charged, put them back up, and was wounded in the attempt. As they drove the Confederates off of Fort Fisher, the 97th maintained itself at the parapet while the rest of the division chased the Confederates to the end of the peninsula to a place called Battery Buchanan, where they finally effected their surrender.

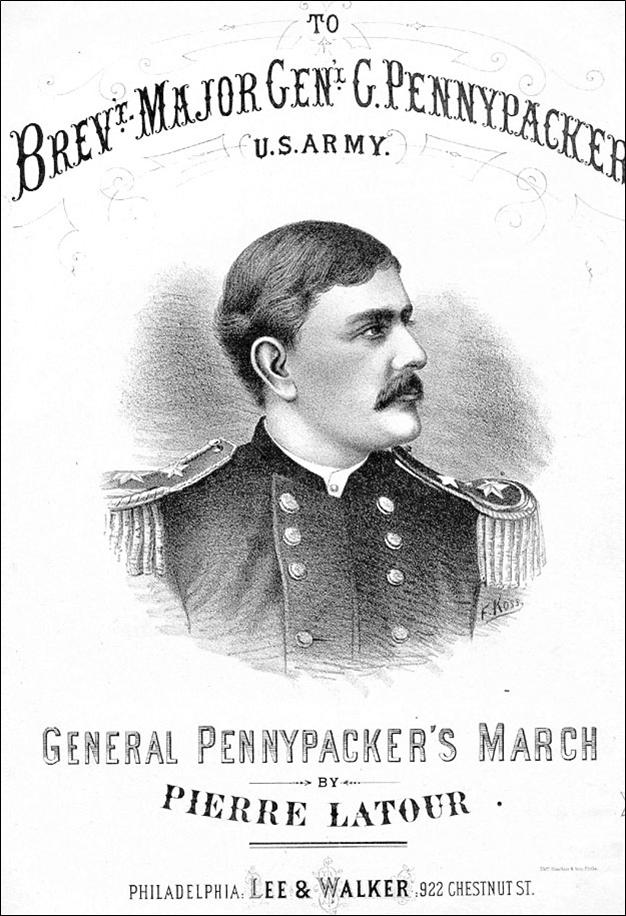

Galusha Pennypacker was born in Valley Forge, Pa. on 1 June 1844. He became a Captain in the 9th PA Volunteers on 2 August 1861. He was brevetted a Major in the 97th, and then made a full Major of the 97th on 7 October 1861. He was made a Lt. Colonel of the 97th on the 16th of May 1864 and a full Colonel of the 97th on the 22nd of June 1864 when he took command of the regiment. In his picture, he looks like a kid. He was. For his action at Fort Fisher on 15 January 1864, Galusha Pennypacker was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor on 17 August 1891. The citation reads: "Gallently led the charge over a traverse and planted the colors of one of his regiments thereon, was severely wounded."

Galusha Pennypacker in his service in the Civil War was wounded four times. Most of his wounds were severe and he wasn't expected to live. He was brevetted a Brigadier General of Volunteers on 28 Apr 1865 at age 20, which means he was the youngest General in the U.S. Army during the Civil War. The war was not over by April 1865. It wasn't over until May of 1866, when President Andrew Johnson finally declared an end to hostilities. There were battles being fought and men being killed as late as July of 1865. Pennypacker was brevetted a Major General in 1867 at age 22, which made him the youngest Major General in the history of the country. He retired from the Army in 1883 and died 1 October 1916. The inscription on his monument which is on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway right in front of the Philadelphia Free Library says: Galusha Pennypacker, Brevet Major General United States Army, 1842 - 1916 (they got the date of birth wrong). The monument does not look like Pennypacker because it's not designed to be a depiction of Pennypacker himself. It's designed to look like a heroic depiction of the bravery that he exhibited on the battlefield in command of his regiment, his brigade, his division.

Question: Did any Union troops come ashore from the Cape Fear River? Answer: No, not from the river. The river was severely mined. Any time they sent Union ships up that river, they never came back. In that battle the Union troops all came from the Atlantic Ocean. They landed from ships; were brought in by ships. Comment: The crater at Petersburg is still there with the door that led to the entryway. We were there 9 years ago. Response: The man who relit the fuse made it out alive. He was nominated for, but was never confirmed and never awarded, a medal of honor. I will tell you, there are tons of Civil War stories about all kinds of... There were probably more medals of honor awarded in the Civil War than in any other war. For two reasons. First, there were no other medals. The federal government offered no other medals. Second, it became quite popular to campaign for a medal of honor and ultimately have one awarded to you. Henry Rees was never awarded his medal of honor. I met a man 8 or 9 years ago in Petersburg and he made it his life's work to try to get Henry Rees his medal of honor. Comment: You mentioned Charleston and it was not a naval battle that you were talking about. But that's also where the Hunley, the first submarine, was lost. It was created by the Confederates and was out trying to sink Federal ships. Response: Not only did it try, it did. The interesting thing about the Hunley is that it killed more rebels than Yanks. Everybody who ever served on the Hunley died. Comment: Galusha Pennypacker was part the Pennypacker family in Schwenksville. Response: The Chester County Historical Society has a Pennypacker display which includes his uniform and his Medal of Honor. Question: What happened to the two commanders who did not lead their men around the crater? Answer: They were summarily discharged from the army in disgrace. Question: Do you know what happened to them later in their lives? Answer: No. I would have had them shot. General Grant was, to put it delicately, sympathetic to their cowardice. Grant himself was not a coward. Absolutely not. But I think he was sympathetic to civilians who found themselves in military situations and didn't quite know how to handle it. Ferrero had been in the 9th Corps for a long time and he had served with Burnside for quite some time. It was Ferrero's Division, along with Robert B. Potter and John F. Hartranft who led the regiments across Burnside's Bridge at the Battle of Antietam. Ferrero did not impress me as a particularly cowardly fellow, but neither was he out exposing himself to enemy fire. Comment: You raise an interesting issue: the why of a professional military as opposed to homegrown militias. It's taken us until today, really, to settle that issue. Response: The people of the U.S. have feared a standing army. After any war has ended, one of the healing cries from the homefolks, and rightly so, I think, is "Let's bring the boys home." We had about 4 million men in uniform in WWII and when the war was over, they couldn't get the boys home fast enough. Comment: We paid dearly at the beginning of Korea with poorly trained, poorly equipped people ready to go in 1950. Response: I suggest to you that after WWI, we brought the boys home and after WWII, we brought some of the boys home and some boys stayed as an occupying force. Maybe they gave up one lesson and learned another. Comment: They made a movie in 2003, Cold Mountain, in Yugoslavia, or somewhere like that, and they recreated the crater and the explosion. When it blows up, it's the hero, a Confederate, that gets injured or wounded and goes back to Cold Mountain. The extent of that explosion is recreated in the movie, but they don't tell the great story that you're telling about the man who relights the fuse and gets it to blow. Response: That's because the Rebels didn't know anything about that. (Laughter). Grant had had a mine dug at Vicksburg. It didn't do any more damage to the Confederates at Vicksburg than the one in Virginia did to the Virginians. There was a southern slave who was just above the explosion when it took place. It blew him about 200 feet in the air and he landed unhurt. He probably spent the rest of his life telling people about how he got blown up: "I was just sitting there and all of a sudden ..." Somewhere in there, there's a book. How much is apocryphal and how much is reality, I don't know. But there are people who claimed to talk to this man. REFERENCE

SOURCES Fox, Lt. Col. William F. Regimental Losses In The American Civil War, 1861-1865. Albany, New York, Albany Publishing Company, Brandow Printing Company, 1889. Johnson, Robert Underwood and Clarence Clough Buel, eds. Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. 4 vols. Edison, New Jersey: Castle, 1887. Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion. 30 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1894-1922. United States. War Department. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. 128 vols. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1880-1901. Roger Arthur has spoken to all the Civil War Round Tables in the greater Philadelphia area as well as Round Tables in New Jersey, Delaware, and Ohio. He is a long time board member of the Brandywine Valley Civil War Round Table. Mr. Arthur holds both a B. S. and an M. A. in history. He has just completed his first book, The Copperhead Vallandigham. This talk was presented at the September 26, 2004 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club. It was transcribed by Bonnie Haughey. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||