|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 42 |

||||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Fall 2005 Volume 42 Number 4, Pages 117–133 GREAT VALLEY AREA LIMESTONE QUARRIES

[Editor's note – Part 1 of this 3-part series about Great Valley area limestone quarries was about the Howellville quarries and was published in the Summer 2005 issue of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly. The quarries at Valley Forge/Port Kennedy will be covered in a future issue.]

The oldest, largest, and longest-lasting of all the quarries in the Great Valley was the one in Cedar Hollow in East Whiteland Township east of Morehall Road—now Route 29, south of Yellow Springs Road, and surrounding the northern boundaries of St. Peter's Church in the Great Valley. The deposits of dolomite limestone here were one of the best in the United States. They were very extensive, easily excavated, and the lime was of very high quality. The major activity here had always been the production of lime in kilns for use in building materials. Clintonville was an early name for Cedar Hollow. Thomas F. Gordon, in his 1833 Gazetteer of the State of Pennsylvania, describes Clintonville as follows: “Clintonville, Chester co. about 12 ms N.E. of West Chester, and 14 from Phila. Contains 6 or 8 dwellings, a woolen manufactory, 1 store and 1 tavern. The vicinity is remarkable for its beautiful limestone.” Clintonville was later changed to Cedar Hollow, taking its new name from the area's once abundance of cedar trees.

Early Cedar Hollow bank-style kiln thought to be near Morehall Road. Photograph by Herb Fry, January 1998. The settlers who lived in the Great Valley in the 18th century were Welsh, English, Scotch-Irish, and Mennonist farmers who engaged in subsistence farming. They made early use of the area's limestone outcroppings. Many had individual bank-style kilns—built into a hillside — on their property to extract lime. At first, their use of lime was to make mortar for the construction of their stone houses, barns, and other structures. They didn't yet know how to effectively use lime on their fields to neutralize overly acidic soil and would sometimes burn out the soil by using too much. Samuel W. Pennypacker, governor of Pennsylvania from 1903 to 1907, was an early promoter of conservation, forestry and game preserves while he was governor. In his Annals of Phoenixville and its Vicinity he wrote: The use of lime, to whose beneficial effects husband- men attribute much of their present prosperity, was commenced by Christian Maris, in 1798. He persuaded a number of his neighbors to go with him to Cedar Hollow and load their teams with the lime, which, as an experiment, upon returning, he scattered over some of the poorest of his fields with a very satis- factory result. [p. 80]. By 1800 this practice was understood. Morrison tells of an 1824 deed transferring ½ acre of “limestone land” in Cedar Hollow to 6 neighbors in Vincent Township, 7 miles away, for a consideration of $125. They were granted the privilege of drawing limestone at any time they needed it from a road on the land. By the early 1830s the liming of fields was a “standard farm practice.” It is reported that “lime frolics” or “lime bees” at farms with kilns were a popular social activity when the kilns were producing. The reputation of the good quality of Cedar Hollow lime was spreading and demand for it was increasing. It was moving from being a product local farmers used to a commodity quarried and marketed by local businessmen. Futhey and Cope report in their 1881 history of Chester County: The large deposits of limestone in the Great Valley and at other points in our county furnish a convenient supply. Forty years ago it was common for farmers to buy the stone at the quarry and haul it near their homes to be burned, but, with the general tendency of all industries to become specialized, the quarry- owner now burns and delivers the lime in the farmer's field, miles away. The ruins of old lime-kilns may be seen in many places by the roadside, remote from any quarry. [pp. 338-339]. Breou's atlas of 1883 shows more than 60 lime kilns in Chester County, mostly in the Great Valley area. As recently as forty years ago the remains of 250 such kilns could be found between Bridgeport and Downingtown.

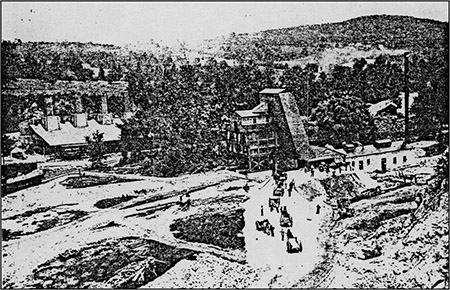

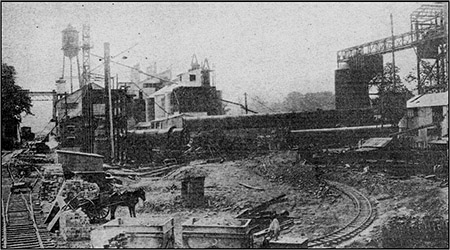

One of he earliest images of quarrying operatons at Cedar Hollow. From the Board of Trade Journal, Wilmington, Delaware. Undated. Courtesy of Sue Andrews. Large scale limestone quarrying began in December 1855 when a group of Philadelphia capitalists, Messrs. English, Larry and Buckman, purchased 60 acres of land in the area for $25,000 and formed the Cedar Hollow Lime Company. No doubt they realized that with the 1853 opening of the Chester Valley Railroad, running between Downingtown and Bridgeport, they could now move limestone and lime to markets in eastern Pennsylvania, Wilmington, New Jersey, and Maryland. In the same year that they formed their company they built a 2-mile spur rail line from their quarry to the Cedar Hollow Station of the rai1road. The station and spur was located west of the Great Valley Presbyterian Church and south of Swedesford Road. A later schedule of the Chester Valley Railroad states that there was room at the Cedar Hollow siding for thirty 44-foot cars. The original bank-style kilns were replaced by kilns with furnaces, known variously as pot kilns or shaft kilns. The pot kilns were made taller and furnaces were added and used in the firing operations of the kilns. Fuel for the furnaces was carried to the top via long chutes. There was a total of 7 kilns and they had to be kept burning round-the-clock in spring, summer, and fall. By 1870 the kilns had brick stacks.

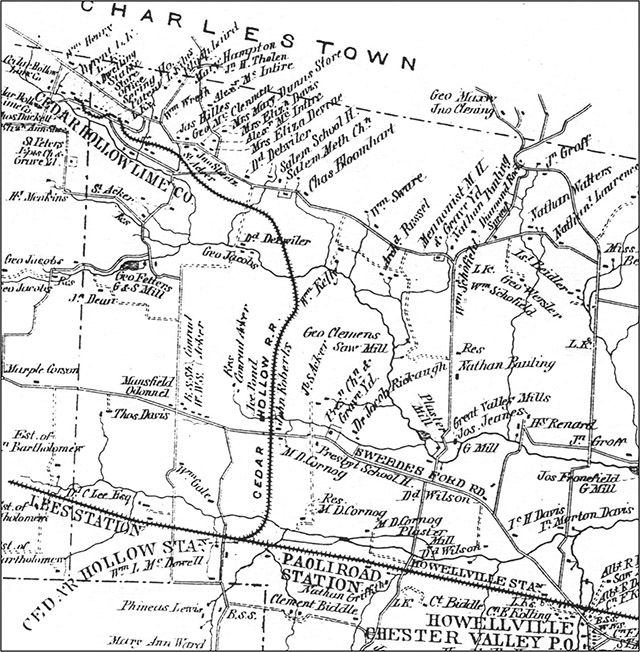

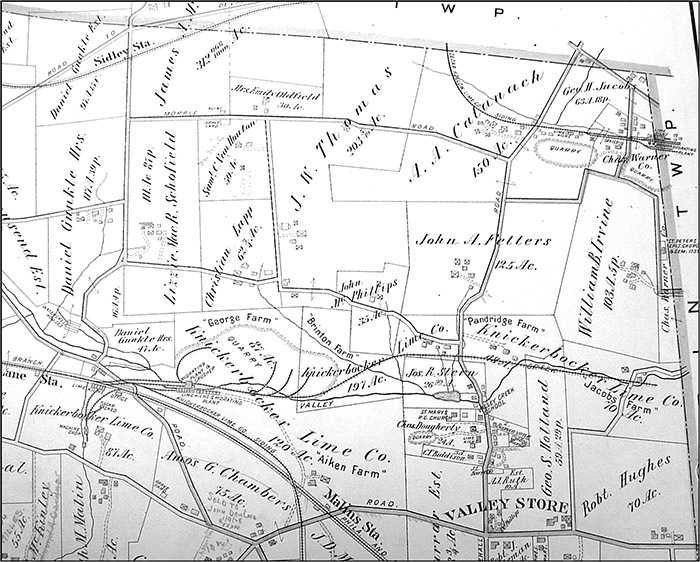

The rail spur line from the Cedar Hollow Lime Company south to the Cedar Hollow Station of the Chester Valley Railroad is shown running down the center of this map. Witmer's 1873 Atlas of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Plate 13, Tredyffrin Township.

The Cedar Hollow Station of the Chester Valley Railroad was built in 1872 on .466 acres of land purchased from William L. McDowell and his wife, Mary, in 1869. It was 1.5 miles NW of Paoli and .5 miles south of Swedesford Road. It faced north and cost $4,150 to build. The style is Carpenter Gothic and it combined a freight and passenger station with a residence for the station master in the south wing and on the second floor. It was heated by stoves and had an outdoor privy. This view is of the north front and west side and shows the extensive freight platform. Photograph by Ned Goode, August 1958. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Historic American Buildings Survey, Historic American Engineering Record, HABS PA.15-PAOL.V.4-1. The earliest workers were the kiln operators who shoveled coal to keep them burning, the quarrymen who crushed limestone with sledgehammers, and the men who tended the horses and drove the horse-drawn trains. The company also built a spur from the quarry north to the Philadelphia, Germantown and Norristown Railroad, which had a terminus in Bridgeport where it met the Chester Valley Railroad. From there the railroad went to a large depot in Philadelphia at Fifth and Jefferson Streets, just north of Fifth Street and Girard Avenue. This was a major place in Philadelphia where builders went to obtain materials for constructing the expanding number of dwellings going up in the city. It is reported that by 1864 the company was shipping about 100 carloads of lime a month and a business notice that year stated that the company would receive wood, hay, wheat, corn, and oats at market prices in exchange for their lime. By 1884 the company was shipping 1,200 bushels of lime a day at $.80 a bushel to Philadelphia and had 30 employees. By 1887 they were shipping 10 horse-drawn trains of 8 cars a day from the quarry to the Cedar Hollow Station. Two years later they had 40 employees. Coal was probably being hauled in to supply the kilns as well as the lime that was being shipped out. Buckman was the company treasurer and came once a month, carrying the workers' pay of $.10 an hour in a black satchel. He set up in the company disbursing office where it took 4 or 5 hours to pay the 60 to 75 workers. The company had arrangements with the local store for settling workers' accounts on payday. By 1898 the Cedar Hollow Lime Company was managed by Robert McCoy, an experienced quarryman, and Edward F. Kane, a Norristown lawyer. By that time 218 acres of limestone were being quarried in Cedar Hollow. One vein extended ¾ of a mile and was 90 feet deep and 1,250 feet wide. A second vein extended for ¼ of a mile and was 90 feet deep and 1,100 feet wide.

Equipment at the Charles Warner Company around 1916 includes a horse-drawn wagon at the bottom left, a small switcher-type locomotive with a driver, at the bottom center, pulling 2 tram cars, and several rail switches. A new big modern rotary kiln stretches horizontally across the middle of this picture. The water tower in the background marks the western edge of quarry operations. Farm Economics, July 1916, p. 31. Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society archives.

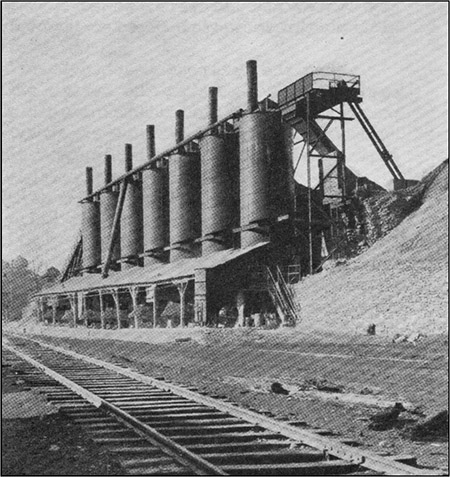

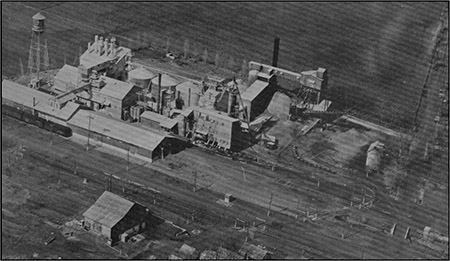

Two views of Warner Company Cedar Hollow operations in 1930. Above: The 7-kiln battery. Below: Aerial view. A string of 13 or 14 small rail cars is barely discernible on the curving tracks in the lower right corner. Regular size railroad cars can be seen at the side of the long rectangular buildings in the middle left. The water tower is still prominent. Both images from Of Gold, Ships, and Sand: The History of Warner Company, 1794-1929, p. 69.

The Warner Company purchased the McCoy interest in the Cedar Hollow Lime Company in 1900 and, at first, retained the name. Charles Warner had received his engineering degree by this time and was the moving force behind the Warner Company's acquisition of the Cedar Hollow quarry. This was Warner's initial foray into a new product line—the cement industry was just getting started in the United States at this time—and it was apparently viewed as a logical extension of their already successful sand and building materials operations. The Warner Company eventually became one of the largest concrete and cement businesses in the United States. An undated article from the Wilmington Board of Trade Journal states that when Warner purchased the quarry in 1900 they added an adjoining property of 128 acres for a total of 218 acres. This article also states that lime from Cedar Hollow was used in making the mortar for the building that eventually became George Washington's headquarters in Valley Forge. The quarry and management that Warner acquired at the Cedar Hollow site were excellent but the plant and equipment were antiquated. Gangs of sledgers were still loading the stone into one-horse carts and hauling them to the top of the brick shaft kilns where the stone was thrown in by hand. The 7 kilns and small portable crusher were obsolete. Charles moved quickly to improve the equipment and expand plant operations. He built sidings and a 24-inch gauge tramway system with horse-drawn cars and a hoist that hauled loaded cars to the top of the kilns where they were dumped. The original battery of 7 brick kilns was modernized with open steel tops and new horizontal patent kilns producing 3,000 bushels a day of lime from all the kilns were installed. Charles further modernized operations by installing an electric power system—until that time there was no power in the Cedar Hollow area—and added a modern stone crusher that processed 1,000 tons a day. He also built stables for the horses but shortly thereafter had small locomotives for transporting cars within the quarry. Daily Life

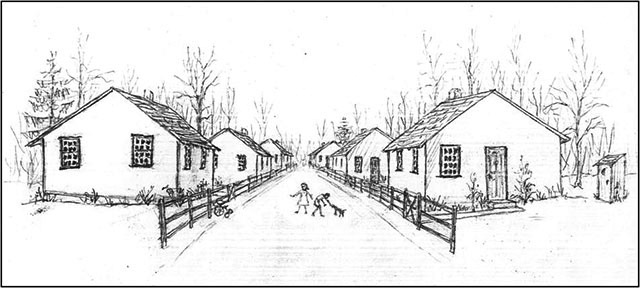

Drawing of the company-built bungalows for workers along Cinder Avenue in Cedar Hollow. None of this remains today. Courtesy of the artist, Sue Andrews.

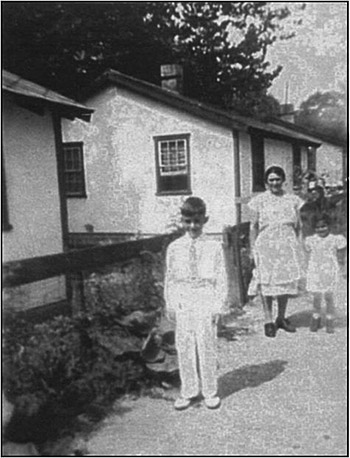

The bungalow on the far left belonged to the Capetola family. Pictured left to right are Emil Capetola, his mother, Antoinette, and his sister, Milena. The Fortunato family lived in the middle bungalow. The Campos family, and later the Jackson family, lived in the bungalow in the background. Courtesy of Lou Capetola and Sue Andrews. With growth more workers were needed. By 1920 Hungarians, Slovaks, Irish, blacks, and Poles were living and working at Cedar Hollow, but mostly there were Italians. It is reported that the Italians, Mexicans, and blacks broke the stone and the Slovaks, Hungarians, and Poles worked the lime. Workers had to be over 18 years of age. The Warner Company built over 50 houses for its workers on the south side of Yellow Springs Road. Some were bungalows that stood side by side in a row along Cinder Avenue—no longer in existence. They cost $7 a month to rent plus $1 a month for electricity. Others, across from where the Cedar Hollow Inn is now, were double frame houses with sloped or pitched roofs. It is reported that the bungalows and frame houses were all painted green and white. In addition, there were 6 poured concrete cubical houses with flat roofs—3 on the south side of Yellow Springs Road west of Morehall Road and 3 on the west side of Morehall Road south of Yellow Springs Road. These concrete houses required very little maintenance and were considered very innovative for their time.

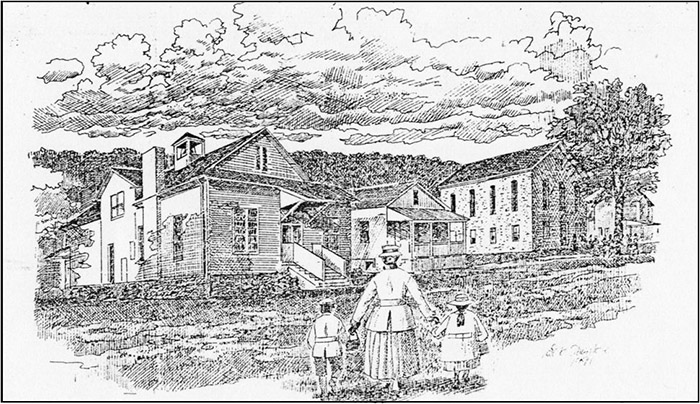

The Salem schools and church. The building on the right next to the tree is the Salem Methodist Episcopal Church founded in 1833. In the middle is the original one-room school and to its right is the larger, more modern school. All the buildings are now private residences. The Evening Phoenix, Home & Garden, July 5, 1991. p. 9 [Phoenixville, Pa.]. Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society archives.

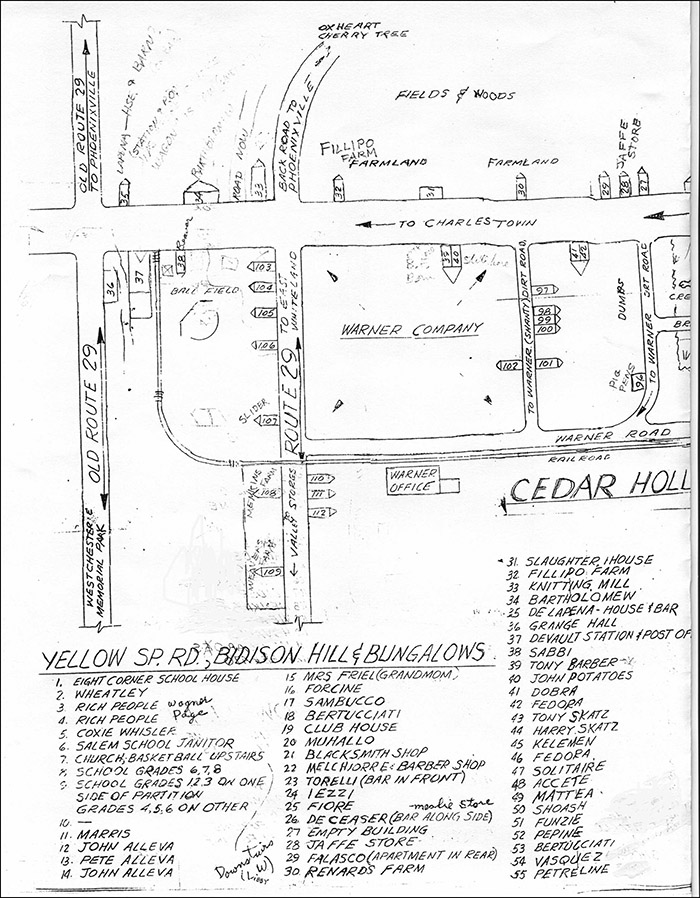

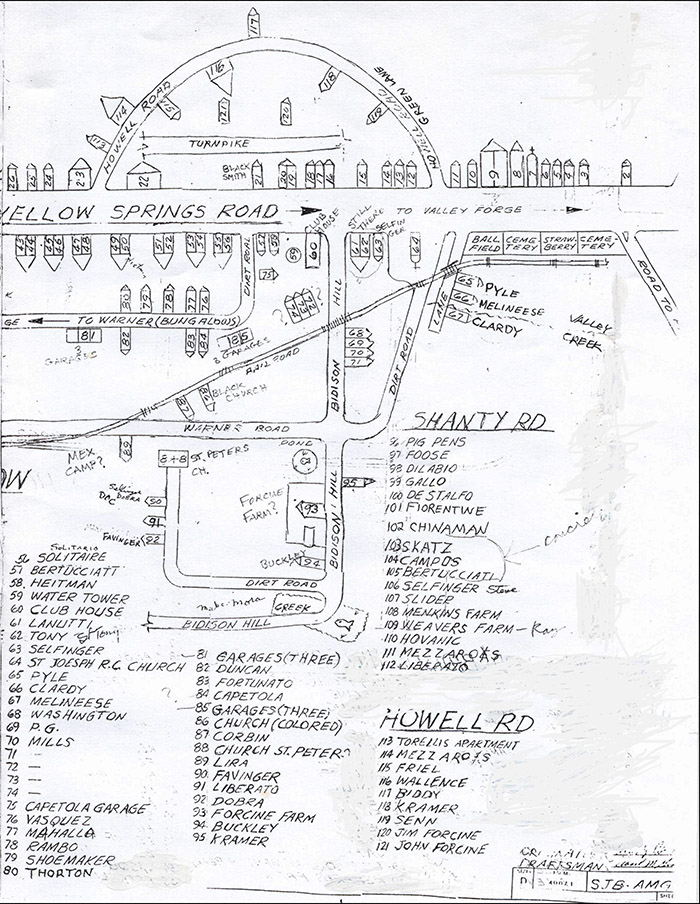

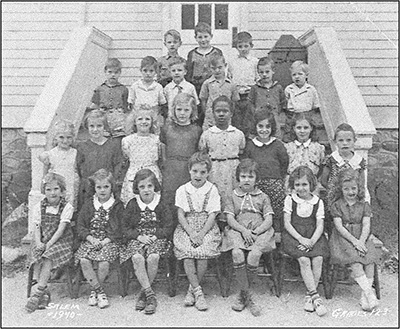

Grades 1 through 3 at the Salem School in 1940. Courtesy of Sue Andrews. In the early 1900s schools were segregated. Blacks had their own church and school. A school for blacks had been started in the area where the Vanguard School is today but was never completed. Children attended the Diamond Rock Octagonal School on Yellow Springs Road before the Salem school was built. By 1921 children attended either the Salem school in Cedar Hollow, the Union school in Charlestown, or the Valley Creek school in East Whiteland. The Salem school closed in 1947. The Warner Company, through an Americanization program, sponsored several social workers who lived among the foreign families in Cedar Hollow helping mothers and children. It was very unusual to find such workers in a rural company village. A July 10, 1916 article by Clarence Sears Kates in the Philadelphia Public Ledger describes a series of patriotic tableaus—drafting the Declaration of Independence, Washington reviewing Betsy Ross' 13-star flag, Washington visiting Lafayette—by costumed native workers for 1,200 foreign quarry workers and their families in an “Americanized Fourth of July” arranged by Miss Young, the social worker at that time. A Daily Local News article of November 3, 1921 describes the activities of another Warner Company social worker, Mr. Elmer Szauer. A series of 4 oral history reports on pages 59 to 72 of the April 2000 issue of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly by men whose families lived and worked in Cedar Hollow includes a wealth of information about what life was like in Cedar Hollow in the middle of the 20th century. Howard Housworth's (pages 59-62) father worked for Warner Company and his family lived in the first —traveling west—of the 3 poured concrete flat-roofed company houses on the south side ofYellow Springs Road west of Morehall Road. It, like so much of Cedar Hollow, was demolished when the section of the Pennsylvania Turnpike east to New Jersey was built in 1950. In the second of the 4 oral history reports in the April 2000 issue of the Quarterly, Emil Capetola (pages 63-64) says Cedar Hollow was a self contained community. He describes the 3 schools, the 2 general stores, the 3 taverns, the entertainment, gardens, and traveling vendors who brought dairy products, meat, produce and clothing in to the villagers. His family's house is #84 on the Cedar Hollow map on pages 124-125. John Alleva (pages 65-70) was born in the house on the northwest corner of Howell Road and Yellow Springs Road [#23 on the Cedar Hollowmap on pages 124-125] that is still standing. When John lived here it was a grocery store run by his family. Later it became Torelli's Bar. His family also ran another grocery store and a bakery in the former Curry general store building to the east on Yellow Springs Road. Pete Melchiorre (pages 71-72) describes things he did as a kid growing up in Cedar Hollow. His family's house and barbershop is #22 on the Cedar Hollow map on pages 124-125. Pete also tells of the important role the Republican Club—at the southwest corner of Yellow Springs Road and what is now Church Road [#60 on the Cedar Hollow map on pages 124-125] and now torn down—played in the life of the village. Warner insisted all employees be Republicans and sponsored this club. The Republican Club was said to have been the scene of turkey raffles, Christmas shows, boy scout meetings, a World War II honor roll on the front porch, and the end of Memorial Day parades where services took place. Matthew Corbin, a Tuskegee airman whose story was featured in the Winter 2005 Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly, grew up in Cedar Hollow. His family's house is #87 on the Cedar Hollow map on pages 124-125 of this issue. The story is told of how the daily blasting operations in the quarry affected the villagers. A siren sounded first to warn of the blast and when it came, household items shook and rattled.

Map showing Cedar Hollow in the late 1930s or early 1940s. Drafted 12/21/92.

Aerial view of the quarry area on September 19, 1988

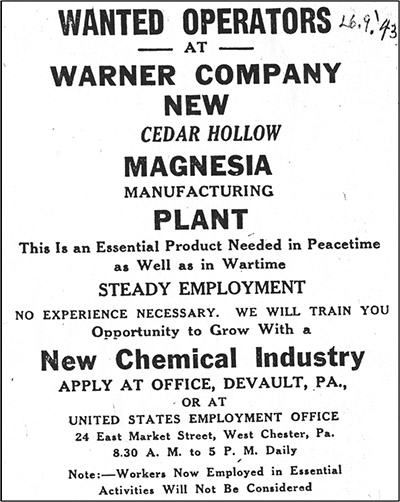

Daily Local News, June 9, 1943. The Daily Local News of December 1, 1947 reports that the Cedar Hollow plant had 49 employees with service records of 25 years or more. But the village was beginning to decline. By the 1950s many of the older workers were retiring and their children, not interested in staying in the village or working in the quarry, moved to Malvern or Phoenixville. As the company houses and bungalows emptied they were not rented again and were eventually torn down. The Coatesville Record of June 14, 1951 reports a strike by 140 workers over vacation time and a 10½ cent raise that lasted 2 weeks. Another strike in September 1953, reported in the September 3, 1953 Daily Republican of Phoenixville, had lasted over 20 days and was for wage increases. Plate 4—Parts of Tredyffrin and East Whiteland Twps—of volume 2 of the 1950 Franklin Survey Property Atlas of the Main Line shows the Warner quarry east of Morehall Road and south of Yellow Springs Road as the Magnesia Division of the Cedar Hollow Plant of the Warner Co. and extending over 230 acres. It continues to show the 2-mile railroad spur south to the Cedar Hollow Station of the Philadelphia and Chester Valley Railroad, previously the Chester Valley Railroad. By 1963 this quarry had extended to over 360 acres.

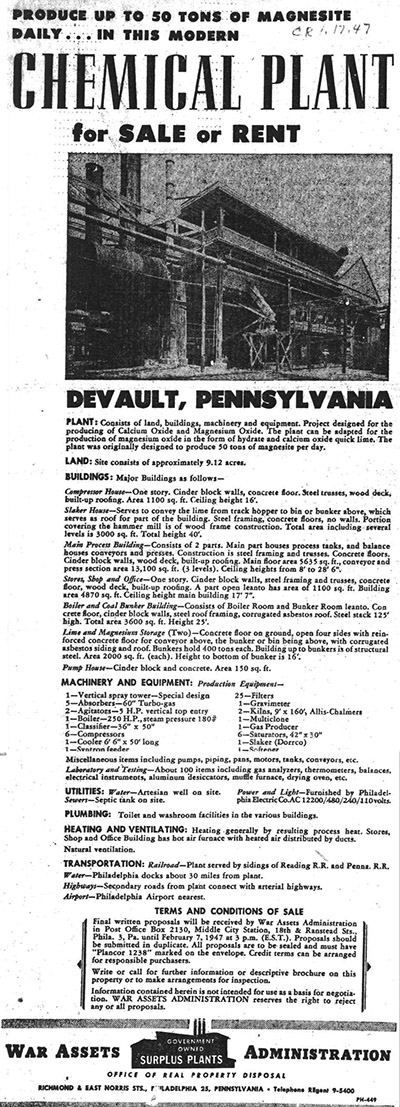

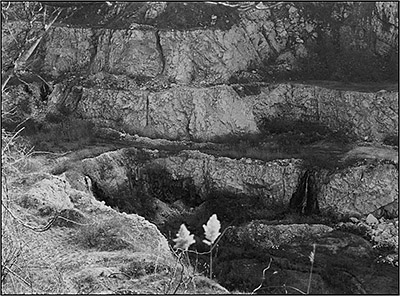

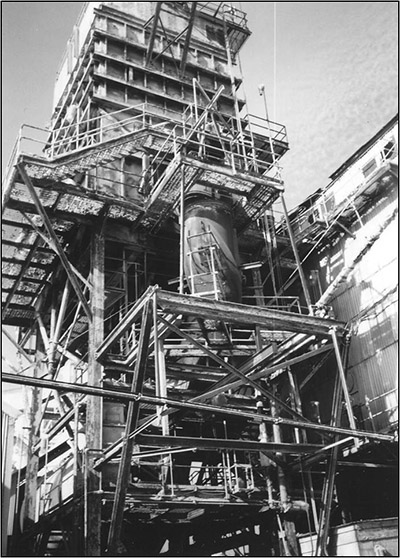

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society archives  The quarry in January 1998. Photograph by Herb Fry.    Three views of the abandoned structures and roads at the Cedar Hollow Quarry in January 1998. Photographs by Sue Andrews.  Scenic lake, looking west toward Route 29, c. Spring 2003 Magnesia is the common name for various chemical compounds of magnesium. At Cedar Hollow the calcium carbonate forming the dolomite limestone was found to also contain high levels of magnesium. This meant the company could expand into product lines other than lime and building materials. A separate plant costing 1 million dollars was built at Cedar Hollow in 1943 by the U.S. government to manufacture magnesite—or magnesium carbonate. This was a much needed chemical during World War II that was used to make refractory brick for steel plants. Fifty tons a day of magnesite were produced at Cedar Hollow, although the plant never reached full production before the war ended. By 1947 this part of the Warner operation was for sale by the U.S. War Assets Administration as reported in the Daily Republican of January 22, 1947. Since Warner's magnesite operations were located at the western end of the quarry near the intersection of Yellow Springs and Morehall Roads and since the small community at this intersection was called Devault, this is the business address that was used. An article in the October 3, 1959 Daily Local News describes the quarrying operations at that time. After blasting the walls, the stone was loaded into trucks and taken to the crusher on the quarry floor. Then it was taken by conveyor belt to the top of the quarry where the pieces were screened by size. The stone used to produce lime was sent to a rotary kiln—300 feet long and 9 feet in diameter —that produced 390 tons of lime a day. The other stone went by conveyor to storage tanks for further processing into limoid and other products. By this time the quarry had been dug to a depth of 100 feet. Two things happened in the 1970s and 1980s that led to the eventual closing of the Cedar Hollow quarry. First, environmental concerns about water pollution and solid waste disposal grew in the 1970s. A new method of treating these pollutants, called sanitary landfill, was patented in 1971 and Warner found it necessary to implement this system at Cedar Hollow that year. This is described in detail in the Daily Local News of June 30, 1971. The railroad spurs stopped running into the quarry in the 1980s. Second, the quarry ran out of the highest quality stone and in 1984 the company issued a request to mine 180 feet deeper into the quarry. The quarry was ½ mile long and ¼ mile wide at this time. Tredyffrin landowners, already concerned about pollution, became very concerned that this new mining would lower and contaminate the local water table and that new blasting would get too close to the foundations of St. Peter's Church in the Great Valley and the Route 29 roadway. Local coalitions pressured the township to impose limits. Warner fought these in court and eventually sold the quarry to Waste Management, Inc. in 1989. The new owner continued to operate the existing lime operations until November 13, 1993. This closing put 84 workers out of work and many of them moved to jobs in the Phoenixville area. Waste Management retained 38 employees and continued the roadstone operations at Cedar Hollow until July 29, 1994. The quarry area stood for many years as a brownfields site considered undesirable for development. In 1999 the state of Pennsylvania passed a “Growing Greener” act supporting the reclamation of abandoned mine properties, the restoration of wetlands, and the preservation of farmland.

On January 1, 2000 the Trammell Crow Company of Conshohocken became the owner and developer of the former Cedar Hollow quarry site. Robert Chagares and Jeffrey Holcomb of Trammell Crow outlined their plans for the 388-acre site at the annual meeting of the Open Land Conservancy on March 14, 2001. It would be called the Atwater Corporate Park. The quarry would become an 80-acre scenic lake 100 to 120 feet deep with the perimeter of the lake beginning 50 feet below the quarry edge. Fifteen 3-story buildings—4 in Tredyffrin Township—totaling 2.5 million square feet of office space would be constructed around the lake. 5.5 million cubic yards of dirt would be moved. Two thirds of the waterfront would be graded. One and one half miles of the track bed of the rail spur that went south to the Chester Valley Railroad would be deeded to Tredyffrin Township to connect the Atwater site to the proposed Chester Valley Trail. Sixty acres along Valley Creek and its tributary, Cedar Hollow Run, near St. Peter's Church in the Great Valley, were to be purchased by the Open Land Conservancy of Chester County. As of October 2005 a formal entrance has been constructed, the scenic lake with imposing cliffs has been created, the site has been graded, one office building has been completed, Route 29 has been widened and rerouted in the area, and several access roads have been added. Plans for future buildings include bioscience laboratories and a hotel.

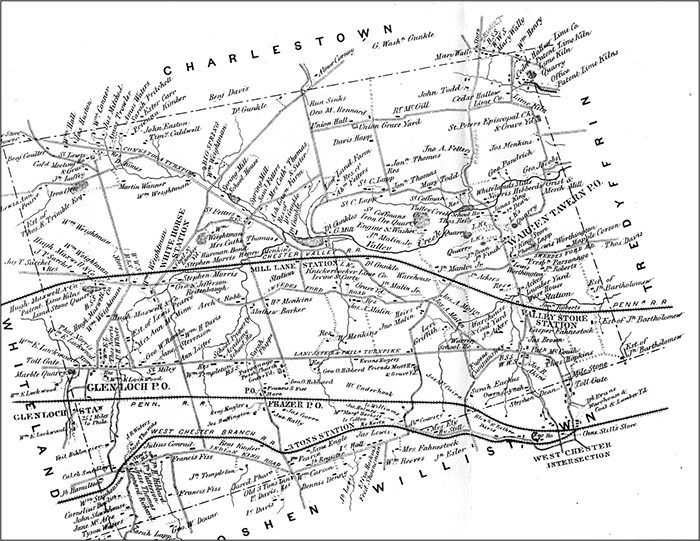

Plate 16—East Whiteland Township—of the 1873 Witmer atlas shows several quarries and other features designated as “L.K.” This plate is crowded in this area with little space for ownership of locations to be written in and it is not clear whether the “L.K.” means “lime kiln” or the Knickerbocker Lime Company which is shown as the owner of a larger quarry on this plate just south of the Mill Lane Station of the Chester Valley Railroad (CVRR). Most of the “L.K.” designations are found to the north and to the west and east of the Warren Tavern Post Office. The directory of local business on plate 16 of the 1873 Witmer atlas illustrates Futhey and Cope's observation quoted above on the growth of specialized local quarry owners. It lists several local business enterprises as being in the lime business. John Dean and Thos. Reily are each listed as an “extensive dealer in lime” with a business address at the Warren Tavern Post Office. The Warren Tavern itself is located on the south side of Lancaster Pike, and although early post offices were often located in taverns, the map on this plate shows a Warren Tavern Post Office several miles north of the tavern on the east side of Morehall Road just north of Valley Store. The dealers, Irvine and Carty, of the Knickerbocker Lime Co. also have a business address at the Warren Tavern Post Office. Another name in this business listing is Hugh Maxwell & Co, an “extensive dealer in lime” with a business address at the Frazer Post Office. Geo. Fulmer, Superintendent of the Cedar Hollow Lime Kilns, is also listed with a business address at the Warren Tavern Post Office. No lime dealers from the Cedar Hollow quarry area are listed on the business directories on either plate 16 or plate 13—Tredyffrin Township—of the Witmer atlas. Plate 15—East Whiteland Township—of the 1912 Mueller Atlas now calls the “L.K” quarries the Knickerbocker Lime Company and shows 5 different parcels of land with this name totaling 522 acres on both sides of Morehall Road north of Valley Store and on both sides of Swedesford Road west of Morehall Road and Valley Store. It shows many railroad sidings from these various quarries converging at a large switching area just

Witmer's 1873 Atlas of Chester County, Pennsylvania, Plate 16, East Whiteland Township.

Mueller's 1912 Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad, Plate 15, East Whiteland Township. north of the Mill Lane Station of the CVRR. From here cars could be either switched onto the CVRR, or sent south on another long Knickerbocker siding to the tracks of the Trenton Cut-Off of the Pennsylvania Railroad, lying to the south of the CVRR tracks, crossing over the CVRR tracks west of the Malins Station to get there. Plate 13—Charlestown Township—of volume one of the 1933 Franklin Survey Property Atlas of Chester County shows that these quarries are now part of the Warner Company. Plate 13—East Whiteland Township—of volume two of the 1950 Franklin Survey Property Atlas of the Main Line shows the Warner Company quarries that were formerly the Knickerbocker quarries now extending over 254 acres. Plate 15—East Whiteland Township—of volume two of the 1963 Franklin Survey Property Atlas of the Main Line shows that 154 acres in the quarry area are owned by Theodore S. A. Rubino and another 43 acres are owned by Rae Crowther. The former siding south to the Trenton Cut-Off is now shown as an unimproved road. By 1970 the quarry was inactive, had been flooded with water to create a natural lake, and was known as the Knickerbocker Sanitary Landfill. Around 2000, Liberty Property Trust purchased a total of 60 acres—the 30-acre quarry and the surrounding area—from the estate of Samuel and Theodore Rubino for between $7 and $8 million. In April 2001 they announced plans for an office building and parking garage, hotel and conference center, and restaurants to be called Quarry Ridge at Great Valley Corporate Center for the northwest corner of the intersection of Swedesford Road and Morehall Road—Route 29. The lake would remain in its natural state as the focal point of the planned development. As of October 2005, a large stone gateway, an imposing 6-story 204,000 square foot office building at 3 Quarry Ridge, and several new access roads have been constructed in front of the lake.

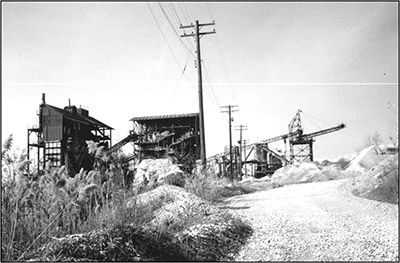

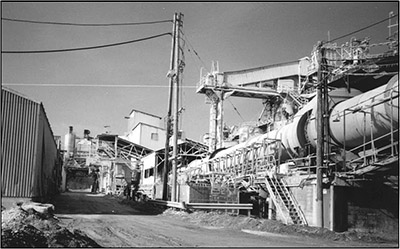

Another quarry, although not as big as Cedar Hollow or Knickerbocker, is this present day plant at 600 Morehall Road, with a Frazer address in East Whiteland Township. It is one of 5 asphalt plants owned by Glasgow, Inc., a heavy and highway contractor and materials producer with offices in Glenside, PA. The rock quarried here is rock asphalt, a mixture of sand, limestone, and asphalt, which, when crushed, is used as road building material. Some time after 1883, a Philadelphia building materials businessman, Adam Catanach, bought a 150-acre farm with a large 3-story house and a barn near Devault on the west side of Morehall Road. This can be seen on Plate 15—East Whiteland Township—of the 1912 Mueller Atlas. In addition to his farm, Catanach had a lime burning business which probably supplemented his Philadelphia business operations. The site of the present quarry does not appear on the Mueller atlas or on any of the other known historical atlases of this period.

Alleva, John. “Cedar Hollow and the Warner Company.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 2000). pp. 65-70. Andrews, Sue. “Old Houses and History of Devault and Cedar Hollow.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 2000). pp. 43-58. Atlas of Chester Co., Pennsylvania From Actual Surveys by H. G. Bridgens, A. R. Witmer and others. Safe Harbor, Pa.: A. R. Witmer, 1873. Atlas of Properties on Main Line Pennsylvania Railroad From Devon to Downingtown and West Chester Embracing Boroughs of Downingtown, Malvern, and West Chester, and Easttown, East Bradford, East Caln, East Goshen, East Whiteland, Newtown, Thornbury, Tredyffrin, Upper Merion, Westtown, West Goshen, West Whiteland, and Willistown Townships. Compiled From Actual Surveys, Official Records and Private Plans by J. M. Lathrop and St. Julian Ogier, Civil Engineers. Under the Direct Supervision and Management of A. H. Mueller, Publisher. Philadelphia: A. H. Mueller, 1912. Baum, Stephanie L. “Cedar Hollow: Former Residents Recall the Heyday of a Company Town.” Suburban and Wayne Times, March 26, 1998. p. 13A. Breou's Official Series of Farm Maps, Chester County, Pennsylvania. Compiled, Drawn and Published from Personal Examinations and Surveys. Philadelphia: W. H. Kirk & Co., 1883. Capetola, Emil. “Life in Cedar Hollow.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 2000). pp. 63-64. Chagares, Robert and Jeffrey Holcomb. “Trammell Crow Company Plans for the Future of the Warner Property and Valley Creek Watershed.” Presentation, Open Land Conservancy of Chester County, 62nd annual meeting, Great Valley Presbyterian Church, Malvern, PA, March 14, 2001. Fahy, Anne. “Opponents Dig in to Fight Growth at Warner Quarry.” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 10, 1989. Futhey, J. Smith and Gilbert Cope. History of Chester County, Pennsylvania with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches. Philadelphia: Louis M. Everts, 1881. Gilliland, Betsy. “Yellow Springs Road Meets the 20th Century.” Main Line Life, History, November 22 and November 29, 2000. Goshorn, Bob. “Farms in the Great Valley and Southeastern Pennsylvania in the 18th Century.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 30, No. 2 (April 1992). pp. 53-70. Housworth, Jr., Howard R. “The Company House at Devault.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 2000). pp. 59-62. James, Arthur E. “Clintonville-Tredyffrin Paper Mill, 1834-1848.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 2 (April 1996). pp. 53-60. [Reprint of a September 1970 original article in The Paper Maker, a periodical published by the Hercules Powder Co. of Wilmington.] Johnson, Kevin L., Chad E. Dixon, and Scott P. Tochterman. “Brownfield Redevelopment and Transportation Planning in the Philadelphia Region.” ITE Journal, July 2002. “Atwater Redevelopment Project,” p. 4. http://www.perspectives.cutr.usf.edu/articles/Trip_Generation/0019.pdf. Massey, George Valentine. Of Gold, Ships, and Sand: The History of Warner Company, 1794-1929. Bellefonte, Pa.: Grove Printing Company, 1978. 111 p. “Cedar Hollow Lime Company,” pp. 68-71. Melchiorre, Jr., Peter. “Notes from a Visit with Pete Melchiorre Jr.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 38, No. 2 (April 2000). pp. 71-72. Metz, Gretchen. “Waste Firm Cuts Section: 84 Lose Jobs.” Daily Local News, November 17, 1993. Morrison, Harlan. “Some Thoughts on Limestone and Lime Kilns in Chester Valley.” Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, Vol. 37, No. 1 (January 1999). pp. 3-8. O'Neal, Sharon. “Mining a Rich Tradition.” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 26, 1992. Pennypacker, Samuel Whitaker. Annals of Phoenixville and its Vicinity from the settlement to the year 1871, giving the origin and growth of the Borough, with information concerning the adjacent townships of Chester and Montgomery Counties and the Valley of the Schuylkill. Philadelphia: Bavis & Pennypacker, Printers, 1872. 1976 reprint. Property Atlas of Chester County, Penna. Complete in Three Volumes. Volume One Including the Boroughs of Downingtown, Malvern, and West Chester, the Townships of Birmingham, Charlestown, Easttown, East Bradford, East Caln, East Goshen, East Whiteland, Schuylkill, Thornbury, Tredyffrin, Westtown, West Goshen, West Whiteland, Willistown, also Newtown Township in Delaware County. Compiled From Official Records, Private Plans and Actual Surveys By and Under the Supervision of the Franklin Survey Company ... Philadelphia: Franklin Survey Company, 1933. Property Atlas of the Main Line, Penna. Volume Two, Chester County Including the Boroughs of Malvern and Phoenixville, the Townships of Charlestown, Easttown, East Goshen, East Whiteland, Schuylkill, Tredyffrin, West Goshen, West Whiteland, Willistown, also Newtown Township in Delaware County. From Official Records, Private Plans and Actual Surveys. Compiled Under the Direction of and Published, Sold and Revised Exclusively by Franklin Survey Company ... Philadelphia: Franklin Survey Company, 1950. Property Atlas of the Main Line, Penna. Volume Two Embracing the following municipalities in Chester County: Townships of Tredyffrin, Easttown, Willistown, East & West Whiteland, East & West Goshen and the Borough of Malvern. From Official Records, Private Plans and Actual Surveys. Compiled Under the Direction of and Published, Sold And Revised Exclusively by Franklin Survey Company ... Philadelphia: Franklin Survey Company, 1963. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the following individuals and organizations for additional information, photographs, and sources: Dan Alleva, Sue and Bill Andrews, Elinor Brandt, Herb Fry, Sheila Kellogg, Roger Thorne, Ted Zugay, Jr., site manager at the local Trammell Crow office, and the numerous files at the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society archives. Joyce A. Post is the editor of the Tredyffrin Easttown History Quarterly. Her Howellville quarries article—part 1 of a look into Great Valley area limestone quarries—was published in the Summer 2005 issue of the Quarterly. |

||||||||||||||||||||