|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 43 |

||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||

|

Source: Winter 2006 Volume 43 Number 1, Pages 3–9 “CITIZENS TO SAVE VALLEY FORGE”

This is a tale of twists and turns, some of them unexpected. Mitzi and I had been living for 20 years in New England. We moved there for me to become sales manager of the National Blank Book Company, in Holyoke, MA in 1956; so now we come back to this area in 1970. The first weekend in our house on Wisteria Drive was Thanksgiving 1970. There's a knock on the door and here are two people saying, “You must help us save Chesterbrook.” We asked, “What's Chesterbrook?” They came in and waved their arms around and convinced us that Chesterbrook was in genuine trouble. I should mention that Chesterbrook, of course, was the name of Alexander J. Cassatt's horse farm of 865-some acres. The proposed Chesterbrook was about to become a small town of 10,000 to 12,000, with an additional 10,000 people coming to work each day in the business and corporate portion of the development. In due course, we joined Citizens Organized to Reclaim Chesterbrook, better known as CORC, pronounced "cork." CORC was a rather confusing organization. People in it had different agendas. Our chairman, who shall remain nameless, was really getting ready to campaign for county commissioner in Chester County, and that gave his input on the CORC organization a real political twist. It lacked focus and was against Chesterbrook, but had positive goals about what to do with Chesterbrook. After a year, we drifted away.

I think it was the latter part of 1972 that Anna Maria Malloy, at that point, was the chair of the Valley Forge State Park Commission, It had 13 members; all appointed politically. Anna Maria and Bill Malloy said, "Why don't you come over to our house for cocktails?" I was flattered and Anna Maria said, "R.T., I know you've been working at CORC, but I want to show you something that is far more important and desperate. The first thing we have are encroachments.” She started with an area by the Port Kennedy railroad station that was to accommodate 2,000 cars. A developer wanted this piece of park land for 2,000 cars. He had big political connections and she was afraid he was going to get it. Why did he want 2,000 cars? It was to supplement a parking area for a high-rise apartment building, which was never built.

East entrance to Valley Forge State Park with the Sheraton Hotel looking out over the park. R. Toland told this story: “They wanted to build a sign with a big ‘S’ fifty feet high on top of the hotel. They got into a terrible fight with Anna Maria Malloy and they were denied the 53 feet. So they said, ‘All right, we'll put up a thousand square feet sign saying “Sheraton.” ’ Meanwhile, they were selling premium rooms that looked out over the park.” 1974 photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy R. Toland, Jr. The next one was much closer to the complex where a visitor's center was located in those days. Here were nine houses owned by elderly people and therefore, obviously, coming up for sale at some point. It was a perfect opportunity for gift shops, hot dog stands, etc. to change the character of the area. One of the most egregious encroachments was the Keene Co. property—an area of 43.6 acres—manufacturing asbestos tiles for ceilings. Big dump areas of raw asbestos were located on the grounds of the factory located within several hundred yards of Valley Forge Chapel and the Memorial Arch. Unlike the other encroachments, this was inside the park. It had been there before the park was put together.

Piles of asbestos at the Keene Corp. site. R. Toland said, “Look at the dump, the dump piles, the asbestos piles left over from the Keene Corporation. Material being dumped from unknown origins. There was a wonderful article in one of the papers asking, ‘Is the park becoming Valley Forge dump?' We took that everywhere and showed it to each one of the Senators that we could collar. Asbestos is a word that gets attention very quickly.” 1974 photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy R. Toland, Jr. The next encroachment was a field along Gulph Road surrounded on two sides by the park. It had been for sale, was lying there fallow, and Anna Maria had spoken a number of times urging that it be acquired. The next thing they knew, it was bought by a developer, who turned around, much to everyone's astonishment, and said, "I think this land should belong to the park. And as a matter of interest, everybody thinks it does belong to the park. It's in a natural state. I am perfectly willing to sell it to the state of Pennsylvania for my cost of the purchase and I'd like to give you two years to make up your mind." Two years went by. The legislature in Harrisburg couldn't, and didn't, make up their mind. So this started a march of new houses being built up to within 300 yards of the Memorial Arch, one house at a time, and on land that, really, if anyone had been using their heads, should have become a part of Valley Forge State Park. Another encroachment on the west side of the park was right across from Baron von Steuben's quarters. Land here was for sale, and here again it was the same problem. Who's going to buy it and when they do, what are they going to do with it? Meanwhile, there were a lot of non-descript stores—one of them was in terrible shape with a lot of junk in front of it, and a gas station, which is still there. It was not exactly a good neighborhood for Valley Forge State Park. And finally—Anna Maria explained—on the southwest flank, was the 865 acres of the Chesterbrook tract which includes the present day 90-acre Wilson Farm Park and the Valley Forge Junior High School.

We started in a leisurely way and called ourselves the Valley Forge Committee. The committee had four members: Anna Maria M. Molloy, Kenneth H. Jordan, Jr., M.D., Stuart Taylor, and myself. We started to learn about what was going on at Valley Forge, and what had gone on, which was much more important. In the fall of 1974, we became steeped in the history of Valley Forge, 1777-78. One of our goals was to recruit someone with standing to be the Chairman of our Valley Forge Committee. We went to Judge Edwin O. Lewis, a federal judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals, Philadelphia District. He was 84 years old. He listened to our tale of Valley Forge and was really interested. Then we popped the question, "Will you be our General Chairman?" He said, "If I was 10 years younger, I'd do it." He steadfastly refused to be chairman. He said, "Valley Forge is far more important than Independence Hall.” He had been chair of the Independence Mall effort; to get that whole thing focused. I asked, "Why do you say that, Judge Lewis?" He looked at me with astonishment and said, "If it hadn't been for Valley Forge, there would be no Independence Hall!" It was true. If our troops hadn't rallied and turned the corner after the absolutely miserable winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, we wouldn't have been able to maintain our independence. In the fall of 1974, we started to make our Washington connections. We went to Nathaniel Reed, undersecretary of the Department of the Interior, because he was in charge of Parks and Recreation. He also happened to be a friend and fellow trustee at Trinity College in Hartford, CT. Nat said, "R.T., acquiring Valley Forge poses a very difficult situation because our budget is stretched beyond belief. Valley Forge is important, but so are other places. Honestly, I've got to be frank with you, I don't know. When you go to the Hill tell me what happens." So we met with the staff of the Senate Subcommittee for Parks and Recreation. Then we met with its counterpart, the House Subcommittee and they seemed interested—for two reasons. One, it was a welcome relief to be talking about something abstract like Valley Forge. And two, it had a good ring to it. They were immediately thinking of political gains. They said, “Tell us some more” and "What have you got to show us?" We suddenly realized, we didn't have anything. They said, “You better get some pictures—a slide show—and you better get your story in transferable form.”

Then the bombshell—one of a number—exploded in everyone's face. The Veteran's Administration (VA) had determined that Valley Forge would make a perfect location for its Mid-Atlantic cemetery. We couldn't believe what they were saying: "We only need 500 acres." Only 500 acres. [The proposed cemetery was to go in the area southeast of the park, just south of the present Welcome center.-Ed.] Everyone said, "Now there is a crisis" and “we've got to get going.” That's when we gave ourselves the name “Citizens to Save Valley Forge” and expanded our committee from four to sixteen, to include:

It was Conrad who did a great job in helping to educate the committee, which needed historical background and information. Valley Forge State Park was under the control of the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission and under the management of the Pennsylvania Forestry Department. That's why there wasn't much history coming out of this park. It was Conrad who came to a meeting and said, “I've got bad news for you.” He'd been doing some research and said, "The first effort to try and convert Valley Forge to a national park—this was before it became a state park—was in 1845. It was undertaken by Daniel Webster and others and it failed.” There had been thirteen different efforts, the biggest of which was a 7,000 person dinner at Philadelphia Convention Hall in 1903. It created a real fervor for getting it to a national park and that failed too. Why did they all fail? Lack of money was one of the reasons—although they say in 1903 money was available. Supporters included important big names. The reason, in my opinion, all efforts failed was a question of local pride. The federal government was not held in great esteem in those days. People said, "What do you mean when you say we need the federal government in here to run this park?! We can do it better. Stand up for your rights. Keep it local." I think that was the major reason, and also politics and, goodness knows, what else. Well, shortly after the VA cemetery bomb Anna Maria Malloy was on her way to work one morning and saw a lot of people digging holes up on the side of the hill by Anthony Wayne's statue. She stopped her car and went over and asked what they were doing. They said, “We're digging test graves. We have a contract for 4 test graves and 32 perc holes.” She said, “Stop!” And they asked, “Well, who are you? We're working for the VA. You're just a part of the Valley Forge State Park Commission.” Anna Maria called the chief of the Tredyffrin Police, who stopped the digging immediately. The case went to the courts and much to everyone's astonishment, the VA won because they'd gotten permission from the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. We couldn't believe it. The commission said, “Oh, we gave them permission to dig test graves, but we won't give them permission for a cemetery.” Anna Maria was furious and called them turncoats. Anyhow, there was a good deal of steam. We called our connections in Washington and said, “We need to see you immediately.” We showed Nat Reed an article about the VA digging test graves and perc holes at Valley Forge. He pushed his chair out and yelled, “Oh, no!” because the Department of the Interior had just lost a major battle at Gettysburg—the same darn issue with the VA. We showed Nat our new slide show. He was very helpful at coaching us about where to go and what to say. But what really made the difference, in my opinion, was Philip Lausat Geyelin, a very good friend of Mitzi's and mine—he was an usher at our wedding. Phil was the editor of the editorial page of The Washington Post. Speaking of publicity, it is absolutely critical to have good connections with the media. It just happened I was staying with Phil and Sherry during my trip to Washington. Phil was a good amateur photographer and asked about my projector and screen, as I lugged them in. When he saw the slide show he was outraged and held a meeting with his staff. He presented the case and asked, “Who is interested in following this up?” Coleman McCarthy put his hand up. The Washington Post gave him five days to research the Valley Forge situation in Pennsylvania. Coleman and his new bride, Maureen, stayed at the Malloys. They had the time of their lives. He checked out everything and found that it was worse than he thought. It was an absolutely hopeless match-up between the VA and “Citizens to Save Valley Forge.” It was an uneven match-up between the VA and the Department of the Interior. There was no question Valley Forge needed help—a lot of help.

Here's what happened. On June 2, 1975, Coleman McCarthy's first op-ed article, “Valley Forge (I): The Second Crucible,” appeared in The Washington Post. The lead paragraph is: “Valley Forge State Park, the site of one of the great moments in the American Revolution, is the center of another kind of conflict that threatens the park's integrity, if not its existence as a national shrine. This is the first of two articles on the economic, political and ecological forces figuring in the current controversy.” McCarthy's second op-ed appeared the next day, June 3rd, with the headline “Harsh Times Return to Valley Forge (II).” “Preserving Valley Forge” also appeared in The Washington Post on June 3rd as the lead editorial. For the first the first time we had something of substance in writing—a major breakthrough. We had struggled to get people to read our brochures. When it gets into The Washington Post, it's a different story. Three pieces in two days. The next week The Philadelphia Inquirer published both of Coleman's op-eds in succession, one day after the other. Other papers must have thought, "There's a dimension here we hadn't understood." Our knocking on the door of the Bulletin and the local papers was over. This was big-time. What we didn't realize was that every time The Washington Post is published, it goes on every Representative's desk, on every Senator's desk, every administration desk, and at the White House, to the President himself. This is very specialized, good circulation. For the first time, we were in gear and accelerating. About a month later, on Wednesday, July 2nd 1975, The Washington Post published another editorial headed “Valley Forge and the VA.” Now they're going to work on the VA. “Rep. George Danielson (D-Calif), chairman of the subcommittee on cemeteries and burial benefits told the Philadelphia Bulletin last week that the decision on Valley Forge belonged to his committee, and that the decision of the Appropriations Committee [to deny any funds for planning, developing or constructing a national cemetery in Valley Forge because there was no justification for developing national shrines as cemeteries or overly concentrating activities at such locations] is not legally binding.” The VA had 3 other possible sites in Pennsylvania: Allenwood north of Harrisburg, Ft. Necessity near Pittsburgh, and Gouldsboro State Park near the Poconos. They're saying, "What's the matter with these sites? Lay off Valley Forge." It makes it official when The Washington Post says, "Come on! The last thing we need now is a squabble between committees." In the end, the VA agreed to pick another place in Pennsylvania. On November 4, 1975 The Washington Post published another lead editorial headed "The Stewardship of Valley Forge.” Now that the VA problem had been solved—at least temporarily—with the choice of Indiantown Gap as the site of the cemetery, it was crucial for the Department of the Interior to stand firm in its original interest in accepting stewardship of Valley Forge and to transfer the park from state to federal control. Almost ten times the usual number of visitors to the park was expected in 1976 for the bicentennial celebration. They said, “If any American parkland deserves the enthusiasm of the Interior Department it is this site of the historic encampment of colonial soldiers 200 years ago.” Three other articles appeared in the Philadelphia papers. “Cemetery Is Inappropriate for Valley Forge Park” was the heading of an editorial by Harry Toland [R. T.'s brother] in The Evening Bulletin on June 12, 1975. “Preserve Valley Forge From Further Inroads” was published in The Philadelphia Inquirer on Sunday, June 29, 1975. “Disputes Still Threaten Integrity of Valley Forge, Park Officials Fear Being Shortchanged” by David Taylor was published in The Sunday Bulletin on August 10, 1975.

The issue of the cemetery wasn't the only thing that had twists and turns. We had very good relations at the White House with President Nixon. After Watergate Gerald Ford was the new President. We never did establish as good a rapport after the Nixon White House. But the bills to make Valley Forge a national park were in both the House and the Senate and they both passed. Bicentennial plans started to take over. People were saying, “Have you heard about the Conestoga wagons? They're going to come from all over the United States and they're going to be right here in Valley Forge,” etc., etc. Attention on signing the bill for the transfer of the park seemed to have evaporated. We became very concerned about this and said, “Where do we go from here? When is President Ford going to sign this bill?” And then word came through—President Ford was going to sign the bill into law on July 4, 1976 at Valley Forge! Wow!

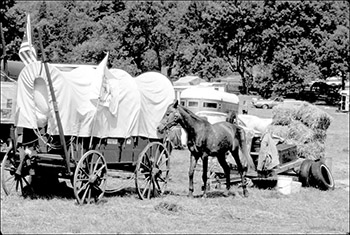

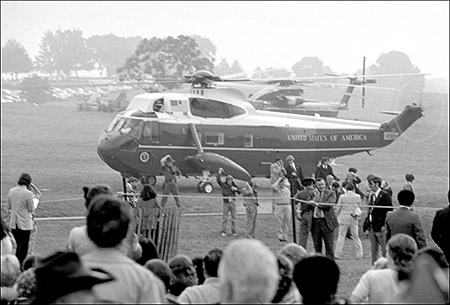

Conestoga wagons, horses, and other vehicles at Valley Forge State Park in July 1976. Photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy R. Toland, Jr. The Conestoga wagons started arriving early. They came in all shapes and sizes. Some of the people came in very authentic looking costumes. The wagons had to figure out for themselves where to park. They parked where they could, making for interesting conglomerations of Amish buggies, cars and trucks, and emergency vehicles. One wagon was from R.F. Smith & Sons Ranch in Texarkana, Arkansas. Another was from Forest Grove, Oregon. Oxen came all the way. People got together. Romance bloomed. Someone wondered if there was a blacksmith—their horse needed a new shoe. People improvised. Here was water hanging on a mirror and there was half a bale of hay. Horses were all saddled up, waiting to go somewhere. Shade was hard to find. There was a fire—one trailer was completely wiped out. July 4th, 1976 was “The Day.” It was hideously hot, for openers. And foggy. You could hardly see more than a hundred yards. And it stayed foggy. The question was the president's schedule: at 10:30 he's coming to Valley Forge, at noon there's going to be a ceremony at Independence Hall, and then on to New York Harbor where he's reviewing a parade of tall ships. But if the fog continues, he won't be able to make it here. He'll have to go directly to Independence Hall, where the visibility is better. Several thousand people were assembled, all the wagons were lined up, the First City Troop was in attendance, there was a podium with a Pennsylvania Conestoga wagon as the background.

This July 4, 1976 photograph at Valley Forge State Park clearly shows the fog. Photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy R. Toland, Jr.

July 4, 1976. Valley Forge is now a National Historical Park. President Ford is waving, and the gentleman to his left, wearing a name tag, is Dick Schultz, local congressman and Valley Forge supporter. Other dignitaries of the day are also seen on the podium. Photograph by R. Toland, Jr. Courtesy R. Toland, Jr. Then ... here comes the President's helicopter. It had started. There were five helicopters. The doors of the first one that landed burst open and out came Secret Service men running in every direction. Then the others put down. The crowd was baffled. Where is the President? There he is. They've changed the name of the helicopter. It doesn't say “President of the United States.” It just says “United States of America.” President Ford couldn't have been more relaxed. He actually did sign the bill making Valley Forge a national historical park into law right then and there. Then he went to the Michigan Conestoga wagon—we were all hoping it would be Pennsylvania's. Forget that. It was time to go. For the first time we were in the Valley Forge National Historical Park—not just a national park—but a crown jewel among the state national historical parks. We'd hit the center of the bull's eye. New things began happening at the park. A much more formal event took place about two months later—the “Ballad of Valley Forge.” It was presented only one time; we've never heard it since then. It was an impressive musical event, with lots of commotion and theatrics; with cannons going off and a “statue” of “Mad” Anthony Wayne. It had a good turnout. There's no question that the presentation of the “Ballad of Valley Forge” marked the beginning of a new era at the park, where expertise, resources, and management are focused on the historical significance of what happened at Valley Forge. “Citizens to Save Valley Forge” was so fortunate to be a part of the transition.

Q: Wasn't there a push to have Chesterbrook become the national cemetery? A: No. It was mentioned along the way, perhaps. Q: What about the current movement for a cemetery at Valley Forge? A: The state park owned land on the north side of the Schuylkill River. Since then quite a lot of acreage has been added above that on the north side of Route 422. But there are also big chunks of land in the immediate area there that aren't owned by Valley Forge. If push came to shove, I'm sure the Department of the Interior would feel that just because they don't own it, doesn't mean that it's not historic and that they would like to own it. The paper reported one comment from the VA, “We've lost the first skirmish but we haven't lost the war.” They love the idea of Valley Forge—there's no question about it. And, boy, do they have political clout. There's no question that the Department of the Interior—and I guess other departments, too—not only get pushed around, but defeated, by the Veterans Administration. They're the government agency with the third largest budget. Their view is that those who fought in World War I and World War II are just as much heroes as our country's first group of army volunteers. It's a matter of opinion. I'm a veteran—a naval aviator—but I don't happen to agree. [At this writing, a tentative decision is to locate this cemetery in Bucks County-Ed.] Q: What is the status of the development to the north, up by Audubon? There was a big dispute about that. Didn't Toll Brothers acquire that land? A: Yes, I think Toll does have it. [At this writing, the status of this development is in dispute-Ed.] I must confess I'm not plugged in any longer to the general situation in Valley Forge so I'm not a good source of information. Q: Is the federal government taking as good care of the buildings as the state did? I've seen some of them with deterioration on the cornices that was awful. A: I was totally amazed myself. Our group had a number of meetings in Maxwell's headquarters. My feeling is that the park is trying to concentrate on what is really historical. And Maxwell's headquarters is a conglomeration of building styles. Maxwell's house could be any one of 18,000 houses in suburban Philadelphia, which means it's been added on to and changed drastically. Q: One of the problems, also at Independence National Historical Park, is that history stops at 1800 for them. But the nineteenth century is history, too. That's the problem with a national park—they often have a narrow focus. A: Yes, they have a myopic view. Gettysburg National Military Park is also a good example. There are good things and bad things about that; pluses and minuses. Robert Toland, Jr. is a graduate of Episcopal Academy, Trinity College, and Harvard University and was a World War II naval aviator. He was in charge of development at the Academy of Natural Sciences and has been a professional developer for 29 years. This was a presentation at a May 15, 2005 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society. It was transcribed by Bonnie Haughey. |

||||||||||||||