|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 44 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: Winter/Spring 2007 Volume 44 Numbers 1&2, Pages 15–19 Inns and Taverns

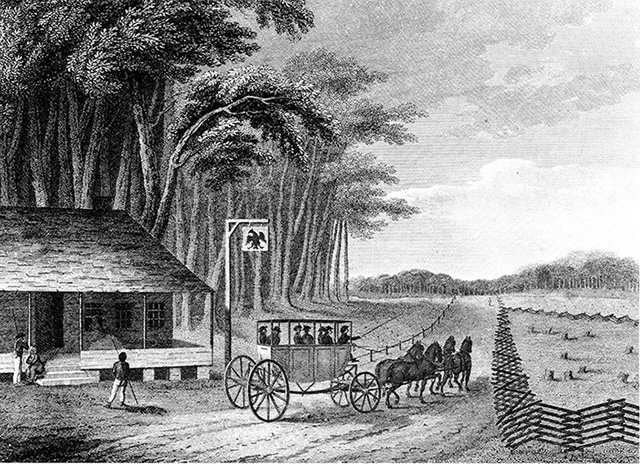

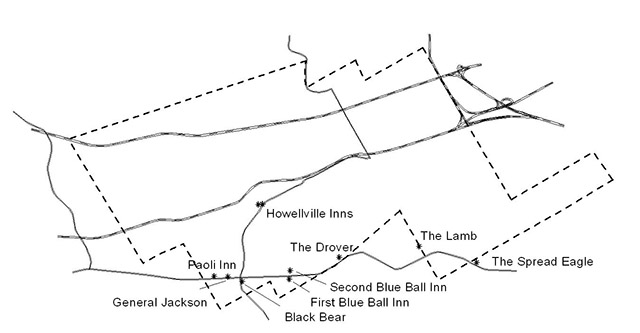

The Spread Eagle Inn, Strafford in the 1790s. The Spread Eagle was just outside the township. The old taverns and inns of Tredyffrin Township were first and foremost essential to the several classes of weary travelers wending their way to and from points west. But they were also equal to the churches in importance as centers of commercial, economic, political, and social life in the early days of the township. They often functioned additionally as post offices, stage coach stops, courtrooms, and military outposts. Taverns were normally located beside major roads. The road on top of the South Valley Hills, known at various times as the Conestoga Road, Old Lancaster Road, and Lancaster Pike (all of which had slightly different routes) was the location of several establishments. A sign at the door with a simple name indicated the class of clientele to which it catered. The first class inns, which were stage stops, bore such names as “King George” and the “Crown.” These quickly became the “General Washington” and “The Eagle” after the war. Second class establishments were the wagon stands, and bore such names as “The Wagon” and “The White Horse.” The third type of inn was the drover's stand, which in addition to the inn, provided numerous pens for the various types of livestock being moved along the road to market. Droves of turkeys, for example, were not uncommon. The last class was the tap stand, like the corner bar of today. Many sold only beer and cider, and were known by such names as the “The Jolly Pot” and the “Cat and Fiddle.”

The Lamb Tavern The Lamb Tavern itself lies just outside the township lines, but the yard and outbuildings were within. It was the easternmost of the Tredyffrin stands on the road to Lancaster and outgrew its original log buildings. In the early days, wagoners hauling pig iron from Warwick and Coventry to Philadelphia frequented the tavern. It remained open into the 1900s when it was converted into a private residence. The tavern was variously known as the Rees store, “The Lamb,” and later “Roughwood.” A Pennsylvania German named Jacob Clinger purchased it in 1815. He and his wife built a new tavern and transferred it into a first class stand for stagecoaches. Later it became a summer home for wealthy Philadelphians, and in 1928 was restored first by the renowned architect R. Brognard Okie, and later by Okie expert William Woys Weaver, who still owns many original artifacts.

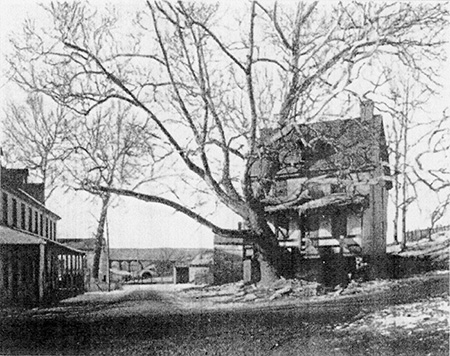

Roughwood 2006 The Drove Inn There were actually two inns called The Drove. The Reese family was associated with the inns, John Reese being the first licensee in 1807, and his son, John Reese junior, the last in 1837. It was turned into a school when business declined with the coming of the railroad. The Blue Ball Continuing westward we come to one of the oldest taverns in the county, the Halfway House, so named because it was equidistant between the Brandywine and the Schuylkill Rivers, and half way between St. Peter's and St. David's Episcopal Churches. During the French and Indian War this inn was the mustering place for the troops and Generals Forbes and Stanwix. In 1757 the license was granted to Thomas Wilkinson, and he renamed the inn the Blue Ball. In 1760 Bernard Van Leer bought the property and leased it to a number of tenant innkeepers, the last of whom was his son-in-law Moses Moore, whose wife inherited the property in 1790. When Moore learned that the new Lancaster Turnpike would bypass the old inn, he sold it and located the second Blue Ball Inn at the other end of the property, on the Old Lancaster Road.

First Blue Ball Inn, 2006 The first Blue Ball Inn survives as a much-altered private home on Glenn Avenue across from Oak Knoll. The second inn, located in Daylesford, became easily the most infamous of the inns, but not until it fell into the hands of Priscilla Moore Robinson around 1826. “Miss Prissey” catered to peddlers and wagoners, many of whom would have been flush with cash from selling wares in the city. It is alleged that many of these men were never heard of again. Was that because each of Miss Prissey's three husbands disappeared mysteriously? Or did Miss Prissy indeed profit from the money? In the 1830s Prissey got very angry at the new railroad that took away business. The issue came to a head when her pet heifer strayed onto the tracks in front of an approaching engine and was killed. When she did not get what she thought was her just recompense she greased the rails with the tallow from the cow so that no trains could pass. She soon received cash for the cow.

A 1900 Locomobile outside the Second Blue Ball Inn The Black Bear The Black Bear stood just below the 18th milestone of the Lancaster Turnpike on what is now route 252. An old house, it was first named “The Bear” in 1785 by Thomas Pennington, who put a large sign out front with “Bear” in gilt letters. First considered a teamster's watering hole, this tavern became a popular place for auctions, and many newspapers advertised sales to be held at the Black Bear in Tredyffrin. It was torn down in 1877. The General Jackson Unlike the quiet, candlelit stone inns that are preserved today, the inns of yesteryear were boisterous, colorful places. A great cloud of dust, shouting men, barking dogs, scattering chickens, and a tooting horn accompanied the arrival of a stagecoach. One such place, anchoring the eastern end of Paoli 175 years ago was “The General Jackson Inn.” It was a well-run place offering additional meeting rooms for the likes of the Farmer's Lodge, and the Free and Accepted Masons.

General Jackson Inn, 1888 The Paoli Inn The Paoli Inn anchored the western end of the Paoli stretch of the Lancaster Pike. It stood on the northwest corner of Route 30 and North Valley Road. Opening on St. Patrick's Day, 1769 it was owned by Joshua Evans, son of one of the earliest immigrants to Chester County. During the evening celebrations on the opening day a toast was made to General Pasquali Paoli, the Corsican general and champion of liberty. Evans liked the name and association, so the Paoli Inn it became.

Paoli Inn, 1888 When the new Lancaster Pike was built in 1794 it went directly in front of the two Paoli taverns, and they entertained a lively, sometimes downright rowdy rivalry. Joshua Evans junior ensured the continued success of the Paoli Inn by getting the railroad to pass by his door. It is said that good dinners and alcohol helped to persuade the surveyors to move the route from its original line in the Great Valley to the ridge of the South Valley Hills. In 1832 the “Paoli” became the terminus of the Pittsburgh stagecoach line. Passengers were then taken from Paoli to Philadelphia by horse-drawn railroad cars. Trains of huge Conestoga freight wagons – horse and mule drawn – transported nearly all of the freight and kept inns like “The Drover” and “The Bear” thriving.

An Election Entertainment by William Hogarth. Taverns, such as the Paoli Inn, were used for auction sales and as polling stations. Pennsylvania passed a law in 1750 which forbade tavern keepers from engaging in “a pernicious custom [dispensing strong liquor] ... to excite such a bid at Vendues [auctions] to advance the Price.” This Hogarth print illustrates an English custom, providing liquor to voters at a polling place. In Pennsylvania, tavern keepers were not allowed by law to give voters “strong drink.” By 1850 the railroads were carrying the passengers, the freight, and the animals, and the heyday of the inns was all but over. That was not before they had served as post offices, places for political and all sorts of other meetings, as polling places, and as sites for many gloriously remembered parties. The Howellville Taverns The last two taverns to be dealt with are the first and second Howellville taverns. As early as 1712 there seems to have been a house of refreshment in the Howellville area. The village sat at the bottom of a natural bowl where 3 roads met to form a triangle. Swedesford Road formed the north side of the triangle and came into existence around 1720. Bear Hill Road formed the southeast side connecting Paoli with the valley. On the southwest side the Howellville Road led up to Cockletown. This triangle created a convenient place for horses to stop and rest, and in 1745 Joseph Mitchell received a license to sell “cyder and beer” at his house along Swedesford Road. He named his place the “Sign of George III.” In 1762 David Howell received the license, and after a few years the inn was known locally as Howell's Tavern. The tavern was a meeting place for Anthony Wayne and other patriots before and during the Revolutionary War. During the encampment in September 1777 British General Charles Grey was quartered there. Mary Howell, David's widow, was innkeeper at the time and filed for considerable losses from her British visitors: hogsheads of rum, whisky, and gin; horses, cattle, sheep, wheat and “6,000 rails of fence.” Captain Christian Fritz received the license in 1801 and named the inn the “General Washington.” Colonel Christian Workizer and his family ran the inn for many years. In 1820 his son, John Workizer, bought the inn from John Howell. He also built the second Howellville Inn across the road, possibly by adding onto an existing structure. Hugh Steen, who ran a quarry, leased the second inn from John Workizer. Eventually the old inn was turned into apartments and later removed to make room for road widening. A sycamore tree, at least 130 years old, was left as the only sign of these old buildings but that has now mostly disappeared as well. The old inns and taverns give us a window through which to see the history of our township from before the Revolution to the early years of the 20th century.

The First (right) and Second (left) Howellville Taverns, c. 1905 |

| Previous Article ⇐ ⇒ Next Article |