|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 44 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: Winter/Spring 2007 Volume 44 Numbers 1&2, Pages 65–67 The School Segregation Fight

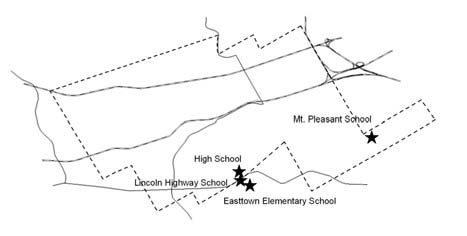

By the early 1930s the townships of Tredyffrin and Easttown had a small but vibrant African-American community, many of whose members had migrated from the southern states to find both employment and equality. While vestiges of segregation were still apparent along the Main Line, white and black children played and attended school together as America entered the depths of the Depression. The schools within Tredyffrin and Easttown were open to every student in their respective township without consideration to his or her color or nationality. Each township elected a school board responsible for the administration of its grammar schools. Each grammar school contained classes for grades 1 through 8. Students from either township entering 9th grade would attend the consolidated Tredyffrin Easttown High School. The Beginning of the “School Fight” In March 1932, the front page of a local newspaper carried the headline “TOWNSHIPS WILL PROVIDE EXCLUSIVE COLORED SCHOOL.” Quoting the president of the Tredyffrin Township school board, the article stated that an agreement by the joint school boards had been completed in which “Negro pupils of Tredyffrin and Easttown townships to have their own grade school ... it is a shame that the building-up process has been stagnated by inadequate schools and the policy of mixing the races therein ... Easttown and Tredyffrin townships are two of the few townships in the State which have not had colored schools.” The two townships planned to jointly operate a “colored school” to be located in a 1912 Berwyn school building at the corner of the Lincoln Highway and Walnut Avenue, to be renamed the Lincoln Highway School. All black elementary pupils from both townships would be assigned to this school, or to the much smaller Mt. Pleasant School on Upper Gulph Road at the far eastern end of Tredyffrin Township. All teachers and janitors at these schools would be “colored.” According to a quote by the joint supervising principal, “colored children progress far more rapidly under colored teachers, who are better able to understand the natures of their children and very often mix with the parents socially and know intimately the home conditions.” Meanwhile, the Tredyffrin School District would bus its white grammar school students to the brand new Easttown Elementary School [at the intersection of Bridge Street and First Avenue in Berwyn], to be opened for the fall 1932 semester. Response of the Black Community The reaction of the black community was one of disbelief that quickly turned into a firestorm of disappointment and anger. On March 16, 1932, Easttown Township's first mass meeting to protest the joint school boards decision was attended by several hundred black, and some white, residents as well as the leadership from the Bryn Mawr branch of the NAACP. It was declared that this decision “tends not toward the betterment and benefit of the conditions surrounding the negro school children, but rather toward the degradation and segregation ... the colored people cannot see why they should be forced to use an old school building no longer wanted by the school board when they, like the white residents of the same section, have paid taxes to support the building of the new $250,000 grade school in Berwyn.” The first small response to what the black community came to refer to as the “school fight” was a petition filled with signatures from the community and taken by a committee of black Berwyn residents to the Easttown School Board. The Board, however, rejected the petition.

Primus Crosby, one of the local leaders of the "school fight. Summer 1932 Ironically, the joint school boards' decision was not only legal, but in fact consistent with the highest court in the land. The U.S. Supreme Court, in the landmark 1896 case, Plessy v. Ferguson, ruled that legally enforced segregation was allowed so long as facilities for blacks were not inferior to those of whites. While the words “separate but equal” were not used per se, the decision stated that such accommodations were permitted under the Constitution. Raymond Pace Alexander, who was the first black graduate of the Wharton School, and a graduate from Harvard Law School, agreed to represent the black parents on a pro bono basis. Starting in August, the joint school board issued official notices to each black parent and guardian informing them that their grade school-aged children would be attending schools specially designated for them in Mt. Pleasant and Berwyn. Busing instructions were provided. Fall 1932 When the Tredyffrin and Easttown fall school term began, both of the schools intended for black elementary children were picketed by parents and by the NAACP. Few of the children entered the segregated classes, and most of their parents held firm to their resolve to boycott the “colored” schools. The “school fight” had begun in earnest. No black attorney had been admitted to the Chester County Bar. With difficulty Alexander found a former District Attorney who supported his application to the bar.

Raymond Pace Alexander Two injunctions were then filed against the Tredyffrin and Easttown school directors and the supervising principal. The Court ruled that it had no jurisdiction in this case, and that the State Attorney General must bring such a suit in order to give it proper legal status. 1933 While the legal fight proceeded in Harrisburg with glacial slowness, no legal effort had been made by the townships to force the black children to attend their assigned schools. In March 1933 a letter from the Pennsylvania Superintendent of Public Instruction was received by the Tredyffrin Township School Board, berating the school districts for refusing to enforce the compulsory attendance provisions of the school laws within its districts. He further challenged why “the State appropriation allotted to your school district should not be forfeited.” By April 1933, notices were sent to all parents and guardians of absent black pupils by the school boards stating that the state compulsory attendance rules would be enforced. These warnings went unheeded, however, and warrants to all parents and guardians of absent black pupils were distributed. Clearly a climax was approaching. The Fining and Arrests of Black Parents and Guardians By October 1933 it appeared probable that a number of black parents would be fined or jailed for failing to send their children to school as ordered. If the children remained truant, the parent was issued a fine until the child returned to classes in his or her segregated school. The fines for violation were $1.00 for the first offense, and $2.50 for each subsequent offense. But this was not a fight about money. On October 19, 1933, the first four black fathers, all from Berwyn, were arrested and transported in handcuffs to the Chester County Prison to begin their 5-day sentences for refusing to pay their $2.50 fine. It was recalled that these four volunteered to lead the scores still to be jailed, and said of the jailing: “Someone has to go first – let it be us.” In the end, a mother with an infant in arms finally broke the cycle of jailings. Recollection names this woman as a Mrs. Williams, who refused on principle to have her fine paid by the NAACP. Knowing that her husband would certainly be fired from his job if he did not show up for work, she agreed to go to jail with her baby in his place so that her husband could keep working to support their family. The crushing logic of her stand caused the court to cease arresting parents. The Final Round The struggle by now had become a political embarrassment, and almost completely partisan. Attorney General Schnader had strong political ambitions to succeed the current governor, Gifford Pinchot. To win the nomination he needed the widest possible support, including the state's black vote. Though Schnader had consistently declined to cooperate heretofore in helping to end the “school fight,” on March 8, 1934 he told a local delegation that he would actively respond to their request for assistance to end segregation of black and white children in Berwyn. Thus, on April 30, 1934, the “Berwyn School Fight” ended. The joint townships school boards notified Raymond Pace Alexander that the segregated system would be eliminated at once. Black and white pupils once again shared the same classroom. Epilogue But the price of victory had been high. So many black children had fallen behind academically, now forcing them to leave their old classmates and be sent back 1 or 2 grades to catch up. Children can be cruel about such things, and jibes are still recalled with clarity over the decades. Many black students who would have been entering 7th or 8th grade in 1932 now chose to leave school permanently in 1934 rather than face taunts of their alleged retardation. Because this case had been settled more on political rather than legal grounds, no clear precedent had been established for others to follow. It would be another 20 years before the case of Brown v. Board of Education was heard before the U.S. Supreme Court in 1954, finally unanimously striking down Plessy and “separate but equal.” And yet, two decades before “Brown”, a lawyer of uncommon brilliance, and hundreds of brave local men, women, and children acted upon their belief that a line in Tredyffrin and Easttown Townships had been crossed, and was worth fighting against. Their fight served as a precedent of what could be done when equality is compromised. |

| Previous Article ⇐ ⇒ Next Article |