|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 44 |

||||||||||||||||||

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

||||||||||||||||||

|

Source: Summer 2007 Volume 44 Number 3, Pages 96–106 THE RYAN CONNECTION The Relationship Between the Main Line Airport, Paoli, Pennsylvania,

This article, an abridgement of a presentation to the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society's January 2007 meeting, is a second article by this author concerning the Main Line Airport, and intended to further illuminate "A History of the Main Line Airport, Paoli, Pennsylvania," published in the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club Quarterly, vol. 40, no. 2 (April 2003).

1939 view of the Main Line Airport along the Swedesford Road in the Great Valley, Chester County. Looking north, the grass runways and several of the airport buildings are clearly visible. The Airport served the fixed-wing needs of the Upper Main Line between 1929 and 1952. Photograph by Thomas Skilton. Courtesy of Orville Jenkins.

When a young airmail pilot named Charles Lindbergh landed at Le Bourget Airport, Paris, on the afternoon of May 21, 1927, having completed the first solo non-stop flight across the Atlantic, he expanded “the realm of the possible”—and brought himself aviation immortality. Lindbergh's airplane, which he named The Spirit of St. Louis after the city of his financial sponsors, was officially designated the Ryan NYP [New York – Paris], N-X-211. It was built by Ryan Airlines, Inc. of San Diego, a company originally started by aviator and aircraft designer T. Claude Ryan in 1925. Though Claude Ryan had sold his interest in Ryan Airlines before the Lindbergh project to pursue other aviation interests, the Ryan name was imprinted upon the collective mind as a synonym for flying achievement and excellence. In May 1934, Claude Ryan incorporated a new firm, based in San Diego, called the Ryan Aeronautical Company. Ryan's first airplane, introduced in 1935, was called the ST, or "Sport Trainer," a low-wing, all-metal, tandem-seat monoplane with a 95 hp 4 cylinder engine. Five ST's were built before Ryan upgraded the ship with a more powerful 125 hp Menasco engine. This modification was called the ST-A (Acrobatic), and became a legend in its own time. Yet, between 1935 and 1940, Ryan Aeronautical would build only 71 ST-As.

The Ryan ST-A, introduced in 1935, is still considered one of the classic airplane designs of all time. Photograph from the Ryan Guidebook. Flying Enterprise Publications, Dallas TX, 1975.

No other event before or since has sparked interest in aviation like the spectacular Lindbergh achievement. By the mid-1930s, aviation fever gripped Chester County, Pennsylvania. At the leading edge of that county's enthusiasm for flying was a Berwyn mechanic and auto racer named Charles Devaney. In the years immediately after World War I, an era before government regulations and flying licenses, Devaney acquired a surplus Curtiss JN-4 Jenny and taught himself to fly from the pastures of his father's dairy farm in East Whiteland Township. Charlie would become a local aviation legend, the first in Chester County to own and fly an airplane. The land that would become the Main Line Airport was purchased in 1916 by Devaney's father, William. This property flanked Tredyffrin Township, and lay on the north side of the Swedes Ford Road.

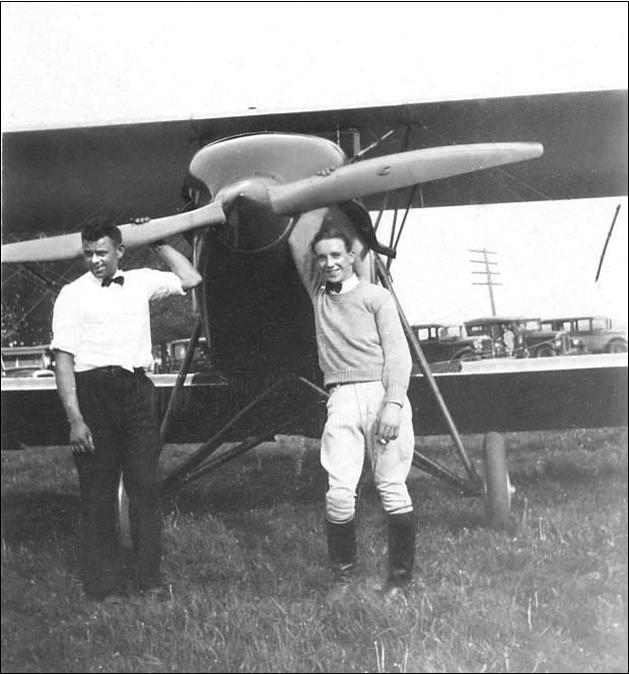

Charles Devaney (left) stands beside his friend Logan Kelly in this photograph taken at the Sky Haven Airport in Goshenville, near West Chester in the summer of 1929. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. In 1929 a consortium calling itself the Philadelphia–Main Line Airport Company had purchased William Devaney's farm to design a helicopter predecessor called an autogiro. During the next 3 years the company successfully built and tested such a craft. In November 1932, the firm relocated the operation from the Great Valley to a former seaplane base along the Delaware River in Essington, PA. This move allowed the former farm to be used solely for recreational flight. The decade of the 1930s saw scores of airplane companies striving to develop the technical and marketing edge to survive within the cut-throat civilian aviation market. Most did not endure. At the Main Line Airport, hundreds of pilots would land and take off on the grass runways in airplanes manufactured by firms like Aeronca, Alexander, Curtis, Davis, DeHavilland, Fairchild, Howard, Piper, Porterfield, Rearwin, Stinson, Taylor, TravelAire, and many more. But none excited the public's imagination more than Ryan, and ST-A is still considered one of the classic airplanes of all time. 1936 was an important year for the Main Line Airport. That June, 36-year-old Charlie Devaney partnered with his 22-year-old friend Nicholas Morris to incorporate an aviation sales and service business which they called Demorr Aeronautical Corporation —a contraction of the names Devaney and Morris. Nick Morris, born in 1914, grew up in Villanova and attended Episcopal Academy. But Morris wanted to fly more than he wanted to attend classes, and left for the sky during his senior year. He became a skilled acrobatic flier and a much-requested flight instructor. Demorr Aeronautical became one of several independent businesses operating at the Main Line Airport, providing flight instruction, aircraft maintenance, and airplane sales. In November of 1936, the Main Line Airport was acquired by the Air Terminals division of the Curtiss-Wright Corporation of Garden City, New York. In March 1937, Demorr Aeronautical took delivery of their first Ryan airplane, an ST-A with registration number NC17343, one of 34 ST-As built that year. Devaney and Morris would log scores of flying hours during the remainder of 1937 giving sales demonstrations, instructing pilots, and providing acrobatic displays at the Main Line Airport and other fields. Few airplanes could attract the crowds and heighten local interest in aviation like the Ryan.

In April 1937, a month after receiving their new Ryan ST-A, Nick Morris (left) and Charlie Devaney proudly stand beside NC17343 at the Main Line Airport. The residence in the background also served as the airport's operations center. Swedes Ford Road runs along the tree line. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. One month later, in April 1937, Demorr Aeronautical succeeded in becoming the official Ryan distributor for eastern Pennsylvania, southern New Jersey, and Delaware. With the universal popularity of the Ryan airplane, obtaining this distributorship was a tremendous boon both for Demorr Aeronautical and the Main Line Airport. Early in 1937, while his ST-A continued to receive stellar performance reviews within the aviation world, Claude Ryan introduced a prototype of his 3-seat, closed-cabin Sport Coupe, or SC. Using the same all-metal fuselage and wings as the ST-A, but with a cantilevered wing construction, the original straight-line engine would be substituted for a 145 hp Warner radial engine. The model was re-designated the SC-W (Sports Coupe–Warner) in October 1937.

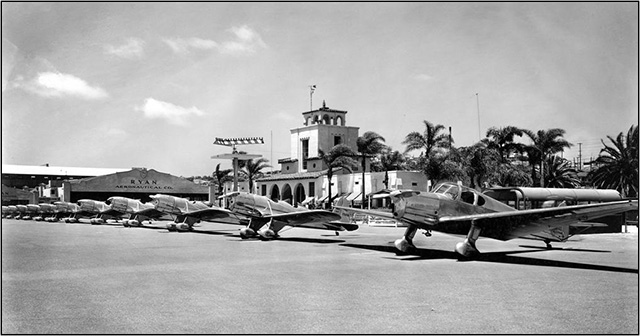

The original prototype of Ryan's SC, with its straight-line engine, is shown in the foreground in the spring of 1937 at Ryan Aeronautical's facility at Lindbergh Field in San Diego. Ten ST-A's are also seen in the background. Ryan publicity photograph provided courtesy of Robert Devaney. Production of the SC-W was to begin in January 1938, and Demorr quickly placed an order to ensure that it would receive the very first issue on the east coast of this new airplane.

By the end of 1937, 21-year-old Malcolm Ashby was the youngest flight instructor in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Anthony Morris. By 1937 flight instruction was a thriving business at the Main Line Airport. Several of its instructors were sought after by aspiring pilots arriving from all over the Delaware Valley. One of those instructors was a 21-year-old from Marshallton, Chester County, named Malcolm Ashby. Malcolm was born in 1916, and had grown up near Goshenville. In August 1932, when he was a 16-year-old student at Tredyffrin Easttown High School, Malcolm soloed in an Aeronca airplane after only 2¼ hours of flight preparation. Malcolm credited his extraordinarily brief training to weeks of instruction in a Waco glider towed behind a car at the old Sky Haven Airport in Goshenville—located near the northeast intersection of the Paoli Pike and Route 352. Ashby received his pilot's license in 1934, and his C.A.A. Air Transport License in June 1936. The ATL enabled him to “instruct for pay,” making him, for a time, the youngest flight instructor in Pennsylvania, and a regular at both the Main Line and the Coatesville Airports. His dream was to become an airline pilot, and he would do most anything to gain the additional flight hours and experience necessary to reach his goal.

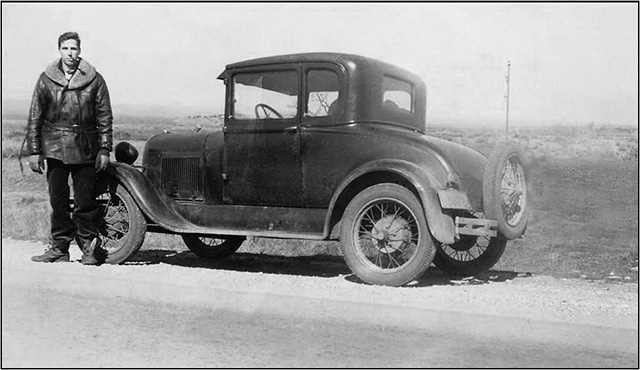

Ryan Aeronautical promised Demorr that its SC-W would be completed and ready for pickup by the end of January 1938. Devaney and Morris decided that Nick and a qualified companion would drive a car from Paoli to San Diego to fly the new airplane back to Paoli. Malcolm was invited to join Nick for the trip. Malcolm recalls: Everybody won by my going with Nick. Other than my expenses, they didn't have to pay me. For a jour- ney of that magnitude, they wanted a second pilot to accompany Nick. I was a qualified flight instructor. I got the benefit of the cross-country experience and the air miles. I enjoyed being with Nick, and he felt the same way. I was fortunate that I could be gone for a month. The education that I would receive would somehow, I felt, have a financial benefit to me in my desire to become an airline pilot in the future. Finally, I had never traveled far from home, and the chance to go to San Diego – and see the Ryan factory – was too good to pass up. It filled in just right for everybody. Malcolm continues: Charlie had obtained a black 1930 Model A Coupe for $29.00, and fixed it up mechanically for the long trip to the coast. I remember it as being rough-look- ing. We did a brake job on the car, and tuned it up— the cost was minimal. We departed on Saturday [January 22, 1938]. We drove continually from day- light till dark, never driving over 50 mph, stopping every 2 hours for a cup of coffee and a driver change, and just kept on going. We stopped every night at a cheap hotel, were on the road at daylight, and would stay on the road until the following nightfall. It was midwinter, but you would still have 12 hours of day- light. We absolutely lucked out on the weather – no blizzards, no snow, I don't even recall a significant rainstorm. We had no mechanical problems [other than 3 flat tires]. On Wednesday evening, January 26, 4½ days after leaving Paoli, we made it to San Diego without incident.

Nick Morris and the Model A on January 25, 1938, three days into their 2,700 mile journey, “somewhere in the southwestern desert.” Photograph by Malcolm Ashby. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. After their marathon coast-to-coast drive, a surprise awaited them! We arrived in San Diego and found our way to the Ryan shop there at Lindbergh Field. It was then that we found out that our plane [production #203, the second airplane scheduled to come off the SC-W assembly line] was not even close to com- pletion. That is when we first met Claude Ryan [who] was a lot younger than I thought he would be. He realized that it would cost a lot of money to send us back east until the SC was ready and then back again to San Diego. Ryan decided to put us up while the airplane was being completed, all expenses paid. We wanted to work together with Ryan, and we were agreeable to stay at an inexpensive hotel that he would pay for. On 3 separate occasions during their stay in San Diego, Morris and Ashby flew familiarization flights in the SC-W prototype, NC17372. Ashby recalls: I remember my reaction was that it was so elaborate compared to anything I had flown before. I could hardly believe that I was having the opportunity to fly a nice airplane like this, let alone on a cross- country flight. It was really a dream for me. The SC was a classy airplane, lovely to fly. Very stable—it would hand-fly itself for a long ways. Looking back on this, I realize now—and I think I realized then—that it was a privilege to fly the original prototype airplane.

Ryan publicity photograph taken around February 7, 1938 showing the SC-W production line in San Diego. The airplane in the foreground is NC18911, production #205, the fourth airplane to come off the line. The Demorr airplane would have been 2 fuselages to the left, production #203. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. Finally, on Friday, February 11, NC18909 was rolled off the production line and taken for a check flight by the factory pilot. But what about the Model A Ford that had so faithfully transported Morris and Ashby across the country? In those days, automobiles purchased in California were significantly more costly than a similar vehicle purchased back east. In fact, one could purchase a car on the east coast, drive it to the west coast, add all one's expenses for travel and repairs, sell the car in California, and end up with a “free” trip. That is exactly what happened. Malcolm recalls that “before we left San Diego, we sold the old Ford to a Ryan pilot for $90.00”—more than 3 times what Charlie had originally paid for it in Pennsylvania.

On Saturday, February 12, 1938, the morning of the departure for Paoli, Malcolm Ashby (left) and Nick Morris (right) stand with their brand-new Ryan SC-W in the background. They flank the Ryan factory pilot who is quite possibly the buyer of the old Model A Ford that transported Morris and Ashby to California. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Anthony Morris.

40-year-old T. Claude Ryan (right), president of Ryan Aeronautical Company, bids a personal farewell to Malcolm and Nick as they prepare to leave Lindbergh Field on February 12, 1938 for their transcontinental return to Paoli in NC18909. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Anthony Morris. Nick and Malcolm took the new plane up for a brief orientation flight the following morning, Saturday, February 12, 1938. Then, that afternoon, with Nick in command, they departed from San Diego on the first leg of their transcontinental return to Paoli. Malcolm recalls: Our flight plan had us flying the short distance to Yuma, Arizona that first day, perhaps 150 miles. When we arrived in Yuma, and at each of the other stops on our return journey, we would have the plane serviced, then catch a cab to a local hotel to spend the night, another cab to the airport first thing in the morning, and take off. It was easy to do that in these small towns. The following morning, Sunday, February 13, they departed Yuma for Abilene, Texas, a journey of 868 statute miles (sm), which took over 7 hours to complete. Monday the 14th they flew 935 sm from Abilene to Knoxville, Tennessee in just under 9 hours. And on the final day of the homeward trek, February 15, 1938, they covered the 545 statute miles from Knoxville into Paoli in only 3½ hours, with a notation in Malcolm's flight log “45 mph tailwind.” They touched down at the Main Line Airport at 2:10 p. m. on February 15th: The SC did not have a radio in it, so when we were approaching Paoli on Tuesday, after all these days away, I do not recall that anyone was even waiting for us. When we taxied up to the farmhouse, I do not remember that even Charlie was there to meet us. Total flying time for the transcontinental journey: 21 hours, 45 minutes. Average speed: 135 miles per hour. Average cruise altitude: 9.000 feet. “Ideal flying weather” all the way. Mission accomplished.

Nine days after arriving at Paoli from their cross-country trek, Nick Morris stands in the cockpit of NC18909 at the Main Line Airport, February 24, 1938. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Anthony Morris.

Claude Ryan had great ambitions for the SC-W, and Ryan Aeronautical was preparing to order assembly parts for an additional 25 airplanes to be built in 1938. But soon after assembly started on the initial production run in January 1938, the War Department placed a significant “priority order” with Ryan for the military trainer version of the ST-A. Ryan did not have the manufacturing capacity to take on both projects, so the SC-W project was sidelined with the expectation of producing the airplane at a later time. The world was moving irresistibly toward conflict, however, and the SC-W project was never resumed. Excluding the prototype, only 11 production SC-W airplanes were completed. After the sale of NC17343, Demorr's first ST-A, and the arrival of SC-W, NC18909, several other Ryan airplanes passed through the Paoli distributorship. ST-A, NC17350, had originally been delivered to another Ryan distributor, O. J. Whitney Co. of Jackson Heights, NY, in April 1937, and subsequently arrived at Paoli in the spring of 1938 for local resale. The aircraft, however, remained at the Main Line Airport until mid-1939, and was repeatedly flown in demonstrations during its stay in Paoli.

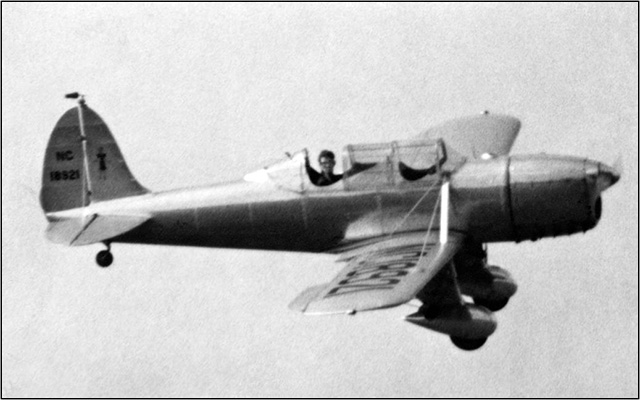

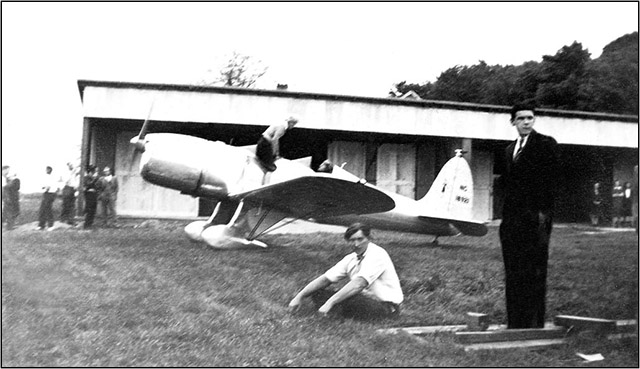

A photograph of ST-A number NC18350 appeared in a summer 1938 Daily Local News with the caption: “Polishing up on his pylon turns at Paoli Airport, Nicholas Morris is caught in his Ryan low-wing plane as Dick Bircher, director of the Philadelphia Air Races next Saturday, watches him.” Courtesy of Anthony Morris. A contemporary photograph of ST-A, NC18902, delivered to Demorr on September 23, 1938 shows the notation DEMORR AERONAUTICAL CORP., PAOLI, PA on the forward portion of the sleek, aluminum fuselage. Insufficient documentation makes it impossible to know exactly when this airplane left Paoli. Another ST-A, NC14913, repeatedly appears in Nick Morris's flight log between October 1939 and August 1940. The aircraft seems to have been acquired by a “Dick Wyman,” who seems to have purchased the older 1935 ST-A with the express intention of having Morris teach him to fly it. Many instructional hours, and the objective of each instruction, are recorded in Nick's logbook as he sharpened Wyman's proficiency. Perhaps this author's favorite story of Demorr Aeronautical and its Ryan airplanes is this one. Last Sunday, [June 25, 1939] about 1.30 p.m., ‘Nick’ Morris, Vice President of the Demorr Aeronautical Corporation at the local airport, was flying a Ryan STA monoplane, attempting to prac- tice ‘blind’ flying through the huge fleecy clouds to the west of the airport. At an altitude of 6000 feet, and traveling at 125 miles an hour, a monstrous plane overtook and passed him less than 500 feet away. The plane was a 74-passenger Pan-American Clipper, recently built by the Boeing Aircraft Com- pany. Powered with four 1500 horse-power engines, it has a cruising speed of over 180 miles per hour. It no doubt was on a practice flight, non-stop to the Pacific Coast. (Daily Local News, June 30, 1939.) Researching the veracity of this spare newspaper account, the author discovered that by June 1939, the last of the 6 giant Boeing Model 314s had been delivered to Pan American World Airways for commercial service. Before each Clipper was inaugurated for service to Pan-Am's Atlantic Division in Baltimore, or its Pacific Division in San Francisco, each ship would complete training flights between the coasts. It is probable that the last of these ships, delivered by Boeing just 11 days before, on June 14, 1939, was returning to the west coast on such a flight when it almost met with disaster over Chester County. As Nick Morris swept up and out of a cloud bank into what he presumed to be clear skies, his tiny ST-A would have been dwarfed by the enormous Clipper bearing down on him less than 200 yards distant. With a cruising speed approaching 200 mph and the tremendous prop wash from the 4 Wright Cyclone engines as it roared past Nick's open ST-A, Nick's shock would have been complete—and perhaps that of the flight crew on the Boeing as well.

When the tri-tailed Model 314 was first flown from Boeing's Seattle factory in June 1938, it became the largest commercial airplane in scheduled use until the coming of the jumbo jets 30 years later. With an operating range of 3,500 miles, Pan American flew many transcontinental training flights between its Atlantic Division base in Baltimore and its Pacific counterpart in San Francisco. One of those flights, directly over the Main Line Airport on Sunday, June 25, 1939, nearly ended in disaster. Image courtesy of Flight Journal. In addition to the 71 ST-As built between 1935 and 1940, Claude Ryan's company built an additional 11 exceptional A-models, called Specials, between 1936 and 39. Equipped with 150 hp supercharged Menasco engines, these powerful Ryan ST-A Specials had a top speed of 160 mph. One of those 11 airplanes came to the Paoli Airport, purchased by Morton Caldwell, a friend of Devaney and Morris, and an heir to the Philadelphia Caldwell jewelry fortune. “Mort,” who became a Demorr Vice President, ordered his ST-A Special in the spring of 1939. The aircraft, NC18921, arrived at the Main Line Airport by truck on July 21, 1939, and was assembled in the Demorr hangar. Mort nicknamed the airplane “Blondie” and a drawing of cartoon character Blondie Bumstead was painted on the airplane's tail.

Above. Morton Caldwell flying his beloved NC18921 in the spring of 1940. During the winter of 1939-40, Charlie Devaney and Nick Morris designed and built a one-of-a-kind canopy for Caldwell's Special, created in the Demorr machine shops at the Main Line Airport. Photographer is thought to be Charlie Devaney. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. Below. Mort prepares for a July 4, 1940 flight in his ST-A Special. A witness to that day's events, student pilot Fred Stanger, recalled: “I watched Mort Caldwell roaring down the runway, taking off in his ST-A with the exhaust blasting. There was no muffler on the engine. He'd take off and fly out; and I'd stand there and think, now that is flying!” Photograph taken and made available by William J. Butler.

Demorr Aeronautical continued as a Ryan distributor until early in 1941, when the franchise was terminated by the cancellation of the SC-W and the majority of Ryan's attention and production capacity shifted to defense work in preparation for a world at war. In April 1940, Curtiss-Wright sold the Main Line Airport to Demorr. By the end of that year the airport was described as “one of the busiest and best equipped airfields of its size in the entire Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.”

With a huge new aircraft hangar under construction in the background, Demorr's SC-W, NC18909, is shown in this August 1940 image. Photographer unknown. Courtesy of Robert Devaney. By early in 1942, with America's involvement in World War II becoming all-consuming, “non-mission” civilian aviation at the Main Line Airport quickly ended. An active Civil Air Patrol squadron was based at the airport through mid-1943, and Demorr Aeronautical secured sub-contracting agreements to produce aircraft parts for the Naval Aircraft Factory adjacent to Mustin Field at the Philadelphia Navy Base.

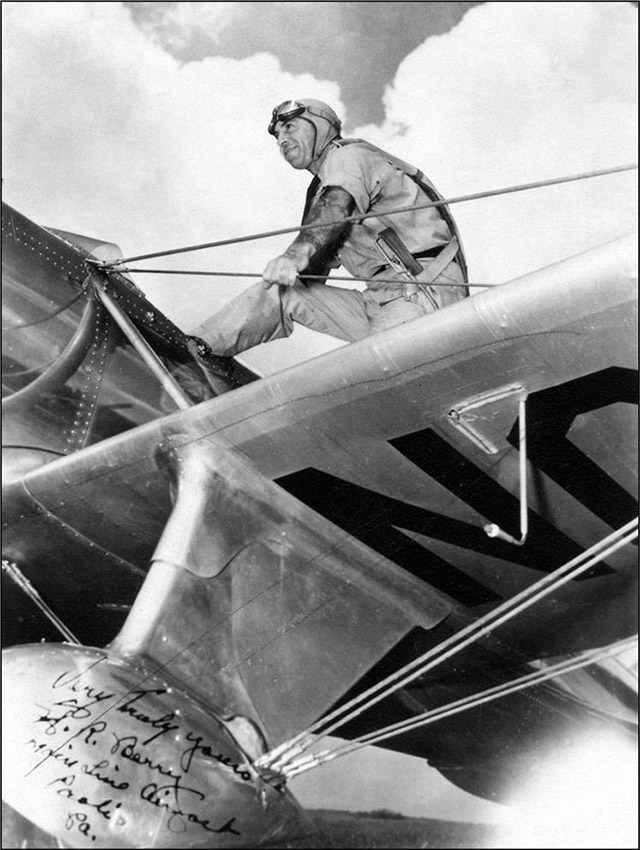

In perhaps the last image of a Ryan ST-A at the Main Line Airport, probably taken in the summer of 1942, Maj. Harvey Berry, the airport's former Assistant Manager during the Curtiss-Wright period and now an officer in the airport's Civil Air Patrol squadron, stands atop what is believed to be NC18902. Photograph by Thomas Skilton. Courtesy of Maj. Berry's son, Joseph.

Charles Devaney, legendary Chester County aviator, entrepreneur, and president of Demorr Aeronautical Corporation in September 1963. He passed away in April 1976 at the age of 76. Courtesy of Charles William Devaney.

Nicholas Waln Morris, linked for 4 decades with Charlie Devaney as a flier, businessman, and friend, died in April 1991. Nick's son, Tony, summed up his dad and aviation this way: “Dad's heart was always in the sky, and in flight, till the day he died. Along with my mother, flying was the love of his life.” Courtesy of Mrs. Peg Morris.

T. Claude Ryan, in an ironic photographic taken in the last years of his life, holds a model of the Spirit of St. Louis, the airplane that would forever be associated with the name Ryan. Yet Ryan had little personal connection with Charles Lindbergh. Six months before Lindbergh's visit to San Diego to arrange a suitable airplane for his transatlantic journey, Ryan had sold his financial interest in the company that bore his name to his associate Frank Mahoney. From San Diego Originals by Theodore W. Fuller, California Profiles Publications, 1987. In 1950 Bethlehem Steel Corporation agreed to purchase several properties including the Main Line Airport to acquire rights to quarry the limestone substrate. Regular fixed-wing flying ceased in 1952. Since the late 1970s, the property once occupied by the Main Line Airport has been entirely subsumed within the Great Valley Corporate Center. With the proceeds from the sale, Charlie and Nick built a modern machine shop a mile south of the old airport in Malvern on the northeast corner of what is today the intersection of Route 30 and Route 29. Continuing under the name Demorr Aeronautical Corporation, the firm became a contract manufacturer producing products like VHF antennas for owners of light aircraft. Charlie and Nick partnered together for a further 14 years after the closing of the Main Line Airport. However, in the mid-1960s, Morris left Demorr Aeronautical to join his family's business, Morris-Wheeler Steel Co., as a sales executive. The parting was very amiable, and Charlie and Nick remained close friends. Demorr Aeronautical Corp. was formally dissolved in 1970. Ryan biographer Theodore Fuller in San Diego Originals, reflected on the legacy of T. Claude Ryan: “In the years following World War II, Ryan Aeronautical built the first jet-plus-propeller aircraft for the Navy, and the first successful VTOL—vertical takeoff and landing—aircraft. His company pioneered remotely piloted vehicles and jet drones, Doppler systems and lunar landing radar.” Teledyne, Inc. acquired Ryan's company in 1969 for almost $700 million in 21st century dollars. In 1982, at the age of 84, T. Claude Ryan died while creating a design for an airplane with simplified controls. “It was a goal that characterized his entire career – making flying easier for more people to enjoy.” And what about Malcolm Ashby, the Chester County flight instructor who accompanied Nick Morris to San Diego in 1938 to pick up SC-W NC18909? Malcolm's dream was realized in January 1940 when he reported to United Air Lines in New York City as a freshly minted First Officer. He became a United Captain in 1942. Ashby's career with United Air Lines was the stuff of legend. During WWII he volunteered as a contract pilot to fly desperately needed ammunition to beleaguered US soldiers awaiting Japanese invasion on Alaska's Aleutian chain. In 1971, by this time Vice President of Flight Operations for United's Eastern Division, Ashby led the company's Boeing 747 transition team, and actually served as captain of United's first commercial 747 flight. In 1976, United's mandatory retirement rule obliged Malcolm to leave the company at age 60. His seniority number, 299, contrasted to a then-current field of over 5,000 United pilots. Malcolm retired with over 27,000 flight hours in his logbooks. Malcolm Ashby celebrated his 91st birthday in March 2007. He has patiently shared with this author his precise memories of grass runways, open-cockpit airplanes, faraway places, and the many good men and women with whom he shared his life in aviation. Quite likely, a personal reflection which he made concerning his own life could also be said to apply to so many who called the Main Line Airport their “home port,” and especially those closest to “the Ryan Connection:” “I was probably the most fortunate guy in the world . . . to love aviation, and to live at a time when the airplanes always got better. It's a great life!”

On January 21, 2007, exactly 69 years after Nick Morris and Malcolm Ashby departed from Chester County on a cold Saturday morning for San Diego to pick up the new Ryan SC-W, the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society met in Berwyn to hear the story of the Ryan Connection - and to honor those who participated and still remember. The presentation was one in a series on the Main Line Airport, early Chester County aviation, and the land—then and now - upon which the airport stood in the Great Chester Valley.

At the conclusion of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society meeting of January 21, 2007, Roger Thorne (left), president of the Society, honors 3 veteran aviators from the old Main Line Airport, (left to right) Capt. Malcolm “Gus” Ashby, James “Buck” Ray, and Orville “Junior” Jenkins.

In quest of information about the old airport, this author has gained far more than he sought - the friendship of many good people who share a common passion for aviation, and with whom many pleasant hours have been spent separating fact from myth, pursuing what really happened at the Main Line Airport so many years ago. They have generously given their time, recollections, information, and photographs, and without their help a project of this detail and relative obscurity would have been impossible. I am very grateful, and would like to especially commend Malcolm Ashby; Orville Jenkins; James P. Ray; William, Robert, and Richard Devaney; and Anthony Morris. The many quotations from Malcolm Ashby describing the trip early in 1938 from Paoli to San Diego, and back, are compiled from scores of interviews the author had with Ashby between 2005 and 2007 and from 4 Pilots Flight Logs, in which Ashby logged some 1,600 hours flying in and out of Chester County between 1932 and 1940, which he loaned to the author. All Demorr records and logbooks are in the hands of the Devaney and Morris families, and Mr. Ashby. Other sources are acknowledged as follows: Daily Local News, West Chester. During the late 930s, a feature on local aviation appeared weekly in the Daily Local News. The primary correspondent for this column was Mr. Harvey “Buck” Berry, a veteran aviator and the Assistant Manager at the Main Line Airport until 1940. Through the auspices of the Chester County Historical Society, which holds microfilm issues of the News going back to the 1880s, this author consulted myriad issues dating from 1937 to 1940 to provide the “human touch” at the Main Line Airport conveyed so well by Mr. Berry. Dorr Carpenter and Mitch Mayborn. Ryan Guidebook. Flying Enterprise Publications, Dallas TX. 1975. “The Spirit of St. Louis.” Charles Lindbergh, An American Aviator. http://www.charleslindbergh.com/plane Technical Preparation of the Airplane Spirit of St. Louis written for the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics. Donald A. Hall, Chief Engineer, Ryan Airlines, Inc. July 1927. http://www.charleslindbergh.com/plane/naca-tn-257.pdf Federal Aeronautics Administration Registry. N-Number Inquiry. http://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/NNum_inquiry.asp Theodore W. Fuller. San Diego Originals. California Profiles Publications, 1987. San Diego Historical Society. San Diego Biographies. Claude Ryan. http://www.sandiegohistory.org/bio/ryan/ryan.htm (no longer available) The Boeing 314, The Flying Clippers. http://www.flyingclippers.com/B314.html Nicholas W. Morris, obituary. Philadelphia Inquirer, April 13, 1991.

Demorr records and logbooks indicate that at least 6 Ryan airplanes passed through the Paoli distributorship between the commencement of the franchise in 1937 and its termination by Ryan in early 1941:

The Ryans were not for everybody's budget.

James “Buck” and his Taylorcraft airplane at the Main Line

Airport in 1940. When viewed in a 21st century context, a Ryan airplane available for $5,000-$7,000 may sound like quite a bargain. But let's place this price in its contemporary context. In 1938, a Chevrolet Master Deluxe automobile could be purchased new for $766. A “cold water” rowhouse in Malvern could be acquired for about $1,800. And a “nice 6-bedroom house with garage” might sell for $4,000. The most popular airplane line at the Main Line Airport in the second half of the 1930s was manufactured by the Taylor-Young Airplane Co. - later renamed the Taylorcraft Aviation Corp.—of Alliance, OH. When new, this 1937 Model A, shown above, NC18313, equipped with a 40 hp Continental engine, sold for $1,495. It was one of 2 purchased by the Malvern Air Service for use in flight instruction at the Main Line Airport. It was subsequently sold in 1940 to 21-year-old James “Buck” Ray for $800. Roger Thorne, a retired sales executive, became president of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society in 2003. He has an abiding passion for early aviation, and this article reflects the third in a series on local aviation presented at the February 18, 2007 meeting of the Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society. |

||||||||||||||||||