|

Home : Quarterly Archives : Volume 44 |

Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society |

|

Source: Winter/Spring 2007 Volume 44 Numbers 1&2, Pages 22–26 The Revolutionary War The Revolutionary War had a major impact on Tredyffrin, both through the indirect impact on the townspeople, as well as being part of the theatre of operations during 1777 and 1778. This war, which was in effect a civil war, aroused a complex set of emotions and impacted the townspeople in various ways. The situation of the Reverend William Currie provides an example. Currie was the Anglican minister with a parish covering this area at the time. He ministered at both St. David's in Radnor and at St. Peter's in the Valley (he also was responsible for St. James' in Perkiomen). In his congregation he had supporters for both sides. During Currie's ordination he took an oath to the church that included the requirement to say prayers for the King, as head of the church. As revolutionary sentiment grew in the area he was pressured to stop saying these prayers, but he was unwilling to break his oath. On May 16th 1776 he resigned his position. Currie still performed baptisms, marriages, funerals, and visited his parishioners, but he did not lead services. Three of Currie's sons enlisted in the Continental Army. One was captured by the British, changed sides, and then fought for the British against the Spanish in Florida. After the war he settled in Nova Scotia. Another son was taken ill on campaign in New Jersey. He returned home, where he died, as did his wife. The Rev. Currie's wife also died, probably from “camp fever,” one of the diseases that plagued the soldiers during the Valley Forge encampment. Currie's farm was plundered when the British camped in Tredyffrin. Currie lost food, clothes, tableware, silver, and farm equipment. Then Lord Stirling, the patriot general, used Currie's house as his quarters during the Valley Forge encampment. The British Campaign General Sir William Howe was in charge of the British Army for the first part of the conflict. One of his strategic goals was to capture the patriot capital of Philadelphia.

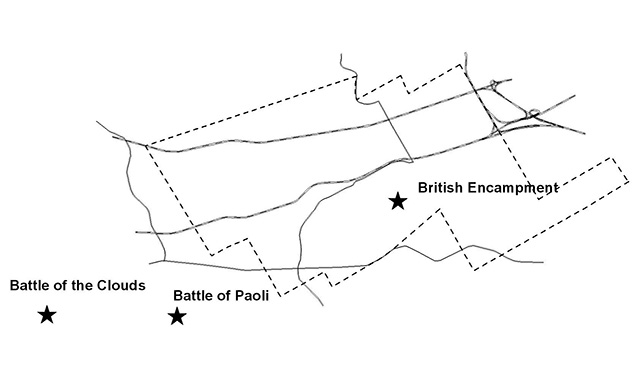

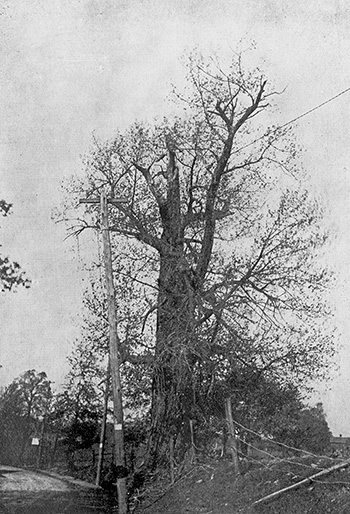

Stirling's Quarters, early 1900s A campaign was initiated to attack southwards through New Jersey from his base in New York. Washington put a stop to that through victories at Trenton in December 1776 and at Princeton in January 1777. The next summer Howe made a second attempt. A large fleet transported his army of 15,000 men by sea and landed near Elkton, Maryland on the 25th August 1777. Washington came south to engage the British and the armies met in the Battle of Brandywine on the 11th of September. Here Washington was out-maneuvered; Howe feinted a frontal attack while sending a contingent north to cross the Brandywine by an upper ford. This group surprised the patriots by appearing on their right flank unexpectedly. Washington had to withdraw and returned to Philadelphia. Howe did not give chase to the patriots, so Washington re-assembled his troops and marched from Philadelphia again to engage the enemy. On the 16th of September the two armies re-engaged. The site of the battle, known as the Battle of the Clouds, was just south of Route 30, between Route 352 and Ship Road, around the site of Immaculata College.

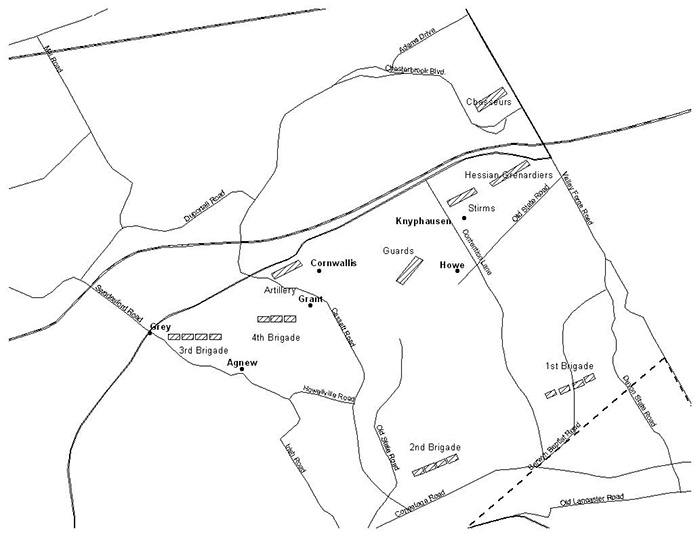

As the battle commenced the weather deteriorated, and as the day advanced it turned into a full north-easterner. In the deluge the guns could no longer be fired, and the patriot ammunition was spoiled. Washington felt he had to disengage. Going back to Philadelphia was too risky as it was not clear whether the army could ford the Schuylkill. If that was not possible then they would be trapped with their backs to the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers and Howe could finish them off. So they retreated to Yellow Springs, and then later to Reading, to dry out and re-equip. On September 18th Howe's army of 15,000 men marched to Tredyffrin, where they camped. The map below shows the position of the British army. The front of the army was at the bottom of the South Valley Hills, facing north. The rear was at the crest of the hills to stop any surprise attack from the rear. The farmhouses where Howe and Knyphausen (who commanded the Hessians) stayed are still standing.

British Encampment & General's Quarters. 18th – 21st September 1777 (including modern roads) Washington decided on a new strategy. Most of the army would be stationed on the far side of the Schuylkill, to block any crossing by the British. A contingent under General Wayne would position themselves behind the enemy in order to attack the baggage train carrying the army's supplies if any attempt at crossing was made. The Forges of Valley Forge Before describing the next engagement, a short history of the forges at Valley Forge is needed as background. The first documented forge at Valley Forge was built by two residents of Tredyffrin, Stephen Evans and Daniel Walker (son of Lewis Walker, Tredyffrin's first settler). In 1742 they purchased a plot of land from William Penn's attorneys and built a forge on the east side of the creek in Upper Merion Township. Evans and Walker unsuccessfully tried to sell the forge and a related sawmill in 1751. In 1757 the operation was acquired by John Potts, the famous iron master. He built a grist mill at the mouth of Valley Creek and further developed the forge as part of his iron-making empire. The two operations used separate dams. The cast iron used by the forge was transported from Warwick Furnace. Locally produced charcoal fueled the forge. Over time the ownership of the forge passed down through the Potts family, and in 1773 the forge was acquired by David Potts and William Dewees. The latter was related to the Potts family by marriage. William Dewees managed the operation at Valley Forge, while David Potts sold the products of the forge from a store in Philadelphia. In 1775 William Dewees built a second forge, known as the upper forge, with its associated dam further upstream along Valley Creek. This forge was on the west side of the Creek, in Tredyffrin Township. Munitions for the Continental Army were made at this forge. William Dewees was a colonel in the militia, and his lower forge, near to the Schuylkill River, was selected as a storehouse for the Continental Army. Dewees was worried that this would attract the British Army (as indeed it did), but after protesting he agreed to take care of the stores. When Washington retreated up river after the Battle of the Clouds, Valley Forge became undefended. The British made a move to take the supplies on the 19th of September. Although Dewees and others managed to get some of them across the Schuylkill to safety, most were captured by the British. The haul was “upwards of 3,800 barrels of flour, soap, and candles; 25 barrels of Horse Shoes; several thousand tomahawks and kettles; intrenching tools; and 20 hogshead of resin.” As they left, the British destroyed the forges and associated dams.

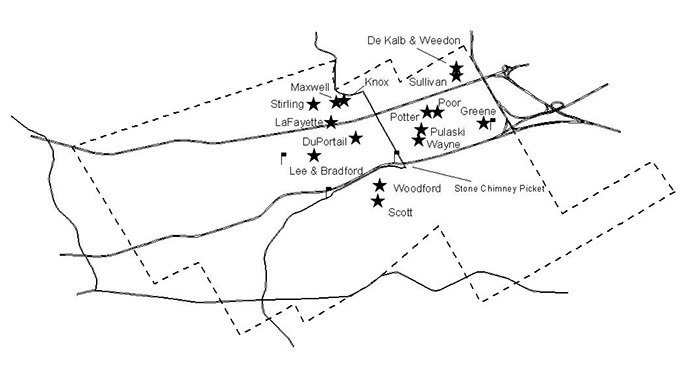

Remains of Upper Forge waterwheel In 1929 the old upper forge was discovered under 7 feet of silt. A 3 year excavation uncovered substantial remnants of the forge; including the remains of the walls, bellows and hammer foundations, water wheels, and raceways. Many of the timbers had been burned. After being uncovered for a number of years the remains were reinterred due to the possibility of damage by floods. The Battle of Paoli Washington decided on one last attempt to stop the British from taking Philadelphia by opposing the crossing of the Schuylkill. He shadowed the British Army from the far side of the river. Additionally, he sent General Wayne with a contingent to harass the baggage train and rear of the British when they started to cross the river. Wayne positioned his troops to the rear of the British Army, camping in Malvern. He initially believed that he had not been spotted, until he got a warning that the British might attack. Even with the warning, a night attack in the early hours of September 21st led by General Grey overran the camp. Wayne's forces were scattered and eventually made their way back to the main Continental Army. Philadelphia In order to get to Philadelphia, the British had to cross the Schuylkill River. Crossing a river was a dangerous time for an army, and Howe wanted to cross without opposition. He feinted a move up river towards the strategic areas of Lancaster County and Reading. Washington responded by moving his army up river. The British were then able to cross the river at Fatlands Ford (in Valley Forge National Historical Park) unopposed. The way to Philadelphia was then open, and the British Army entered the city on the 26th of September. Valley Forge Encampment By the end of 1777 General Howe and his army were well ensconced in Philadelphia. Washington brought his army to winter in Valley Forge on December 19th. The story of Valley Forge has been told many times, and will not be retold here. Instead the focus will be the impact of the armies on Tredyffrin. Most of the encampment was in Upper Merion; only the south-west corner protruded into Tredyffrin. Here the Pennsylvania regiment was camped in what is now called Wayne's Woods. The Virginia troops were to their west side and the New York regiments to their east. The officers of the army found accommodation in the nearby farmhouses. Within the present confines of Valley Forge Park and in Tredyffrin are Knox's, Maxwell's, Stirling's, and Lafayette's quarters. Outside the Park, but still within Tredyffrin were Duportail, Lee and Bradford, Woodford, Scott, Wayne, Pulaski, Potter, Poor, Sullivan, and De Kalb and Weedon's quarters. Most of these houses are still standing and are shown on the map below.

General's Quarters and Picket Posts A ring of sentries encircled the encampment to warn of a surprise attack by the British, and to control entry and exit from the encampment. The sentries were based at picket posts. The position of most of these pickets has long been forgotten. A few of those in Tredyffrin are shown on the map. One, the Stone Chimney Picket, is marked by a plaque, placed there by the Tredyffrin Easttown History Club in 1939. It is on the west side of Route 252, just north of the junction with Route 202. Here the soldiers of the picket made a bivouac against an old stone chimney. Markets were set up to supply the encampment including additions to the basic soldier's fare. There were markets every Monday and Thursday at the Stone Chimney Picket. Markets were also held on the east side of the Schuylkill every Tuesday and Friday, and at the Adjutant General's office every Wednesday and Saturday. Many of the soldiers would not have had the cash to buy anything.

As well as picket posts there were also outposts further away from the encampment. A signaling system was set up for communicating between outposts and the camp. Soldiers were stationed in the tops of trees. These trees were often chestnuts as they were one of the tallest trees in the woods. Chestnuts were the most common tree seen in the woods in this area, but were eliminated in the first years of the 20th century by chestnut blight. The picture shows the sentinel chestnut tree in Strafford in 1909 that was used as a lookout. The remains of a platform built near the top by the soldiers could be seen for many years after the encampment. The Continental Army marched out of Valley Forge on the 19th of June 1778. Tredyffrin was not directly affected during the remainder of the War and was left to recover. In 1782 the residents of Tredyffrin made a list of the material plundered by the British, prior to submitting claims in Congress for restitution. None of the Quakers in the township made claims, but even so 30 claims were registered. |

| Previous Article ⇐ ⇒ Next Article |